The subtle tyranny of the fragmented workday remains one of the most insidious threats to professional excellence in contemporary healthcare. Picture the healthcare consultant who begins their morning with ambitious plans to develop a comprehensive, bespoke treatment strategy—only to find themselves derailed by a succession of brief meetings, each seemingly innocuous, yet collectively devastating to the day’s intended purpose. By afternoon, that carefully considered treatment plan remains unwritten, replaced instead by a shallow patchwork of administrative responses and half-completed thoughts. This scenario isn’t merely frustrating; it represents a fundamental mismatch between the structural requirements of deep, meaningful work and the operational realities imposed by conventional scheduling practices.

In 2026, as Australian healthcare continues its evolution towards personalised, holistic care delivery, understanding the distinction between maker time and manager time has never been more critical. This isn’t simply about productivity optimisation—it’s about creating the conditions under which healthcare professionals can deliver the thoughtful, comprehensive care that patients deserve and that professional integrity demands.

What Are Maker Time and Manager Time?

The conceptual framework distinguishing maker time from manager time originated from Paul Graham’s seminal 2009 essay, “Maker’s Schedule, Manager’s Schedule.” This foundational work identified a critical insight: different types of professional work require fundamentally different approaches to time structuring, and conflicts arise not from personality differences but from structural incompatibilities between these schedule types.

Manager time operates on a schedule divided into small, hour-sized (or smaller) time slots, each with a predetermined purpose. This approach, embodied in traditional appointment books and digital calendars, provides the flexibility managers need to coordinate activities, gather information, make decisions, and delegate responsibilities. For those operating on manager time, meetings represent the primary medium through which work is accomplished. As Andrew Grove articulated in “High Output Management,” meetings aren’t interruptions to managerial work—they are the work itself.

Conversely, maker time requires organisation in units of at least half a day, with minimum blocks of three to four hours for meaningful work completion. Makers—including programmers, writers, designers, healthcare consultants developing treatment plans, and researchers—create tangible value through sustained concentration. Their work cannot be effectively divided into hour-long segments without substantial productivity losses.

This distinction isn’t about superiority or hierarchy. As Graham noted, “Managers would be useless without makers, and makers would be frustrated without managers.” Both roles remain essential to organisational success. The critical insight is this: each type of schedule works fine by itself; problems arise when they meet.

Why Do Different Work Types Require Different Schedules?

The fundamental requirement distinguishing maker work from manager work centres on the necessity of achieving and maintaining flow state—that optimal psychological condition first described by Mihály Csíkszentmihalyi in 1990, characterised by complete absorption in an activity where work feels effortless and time disappears.

For makers, reaching this flow state requires approximately 15 to 30 minutes of uninterrupted concentration. However, the fragility of this state cannot be overstated: a single notification can instantly shatter it, even if not directly responded to. University of California, Irvine research demonstrates that after an interruption, professionals require an average of 23 minutes to fully regain focus—a finding with profound implications for workplace scheduling.

Consider the cascading impact of a single 30-minute meeting scheduled at 11:00 AM. This appointment doesn’t merely consume 30 minutes; it effectively bisects the entire day. The morning becomes compromised because the maker cannot achieve full immersion knowing an interruption looms ahead. Post-meeting, the maker must invest another 15 to 20 minutes minimum in focus recovery. The actual productivity cost of that 30-minute meeting exceeds one hour, and this calculation doesn’t account for the psychological cascading effect—the diminished motivation to start ambitious projects when the day ahead appears fragmented.

Ray Ozzie’s “Four-Hour Rule” captures this reality perfectly: never commence product work unless a minimum of four uninterrupted hours are available. Small time blocks inevitably result in more errors and compromised quality in complex work requiring sustained focus for proper execution.

For managers, however, this calculus differs entirely. Their work thrives on the ability to make rapid, intelligent decisions across multiple domains. A three-minute interaction can generate enormous value. Speculative meetings—getting to know colleagues without extensive planning—serve legitimate managerial purposes. The manager’s schedule naturally accommodates interruptions and context switching because these represent the operational environment in which managerial work flourishes.

How Does Context Switching Impact Professional Performance?

The cognitive costs of context switching extend far beyond simple time accounting. Research published in Harvard Business Review (2022) reveals that the average knowledge worker toggles between applications and websites approximately 1,200 times per day. Workers collectively spend almost four hours per week merely reorienting themselves after switching applications—accumulating to approximately five working weeks (roughly 9% of annual work time) lost annually to context switching alone.

The Qatalog and Cornell study findings prove particularly alarming: the average time required to return to productive workflow after toggling applications reaches 9.5 minutes. Each interruption isn’t merely a momentary distraction; it levies a significant “attention tax” on cognitive resources.

| Performance Metric | Impact of Context Switching | Research Source |

|---|---|---|

| Focus Recovery Time | 23 minutes average to fully regain concentration | UC Irvine |

| Daily App Toggles | 1,200 switches between applications/websites | Harvard Business Review (2022) |

| Weekly Reorientation Time | 4 hours spent reorienting after switching apps | Harvard Business Review (2022) |

| Annual Productivity Loss | 5 working weeks (9% of annual work time) | Harvard Business Review (2022) |

| Workflow Re-entry Time | 9.5 minutes average to resume productive work | Qatalog/Cornell |

| Productivity Reduction | 20-80% decrease (depending on change frequency) | Multiple studies |

| IQ Point Drop | Up to 10 points from chronic multitasking | Cognitive research |

| Global Economic Cost | $450 billion annually from context switching | Economic analysis |

Context switching creates what researchers term a “response selection bottleneck” that demonstrably slows thought processes and decision-making capacity. Frequent multitasking can cause a drop of up to 10 IQ points—a cognitive impairment equivalent to losing a full night’s sleep. Working memory contains only three to seven pieces of information simultaneously; context switching systematically overloads this limited capacity, causing significant declines in cognitive function, particularly for knowledge workers whose primary asset is their thinking capacity.

The neurological consequences prove equally concerning. Chronic context switching produces measurably less grey matter in prefrontal cortex regions—the very brain areas responsible for sustained concentration. Less grey matter translates directly to reduced ability to maintain focus for extended periods, creating a vicious cycle where frequent interruptions physically diminish the brain’s capacity to resist future interruptions.

For healthcare professionals, these statistics take on heightened significance. A UC Irvine study demonstrated that after just 20 minutes of repeated interruptions, participants reported significantly elevated stress, frustration, workload perception, effort expenditure, and pressure. Forty-five per cent of workers describe toggling between too many applications as mentally exhausting, whilst 43% report it diminishes productivity. Over one-third feel overwhelmed by persistent notification alerts.

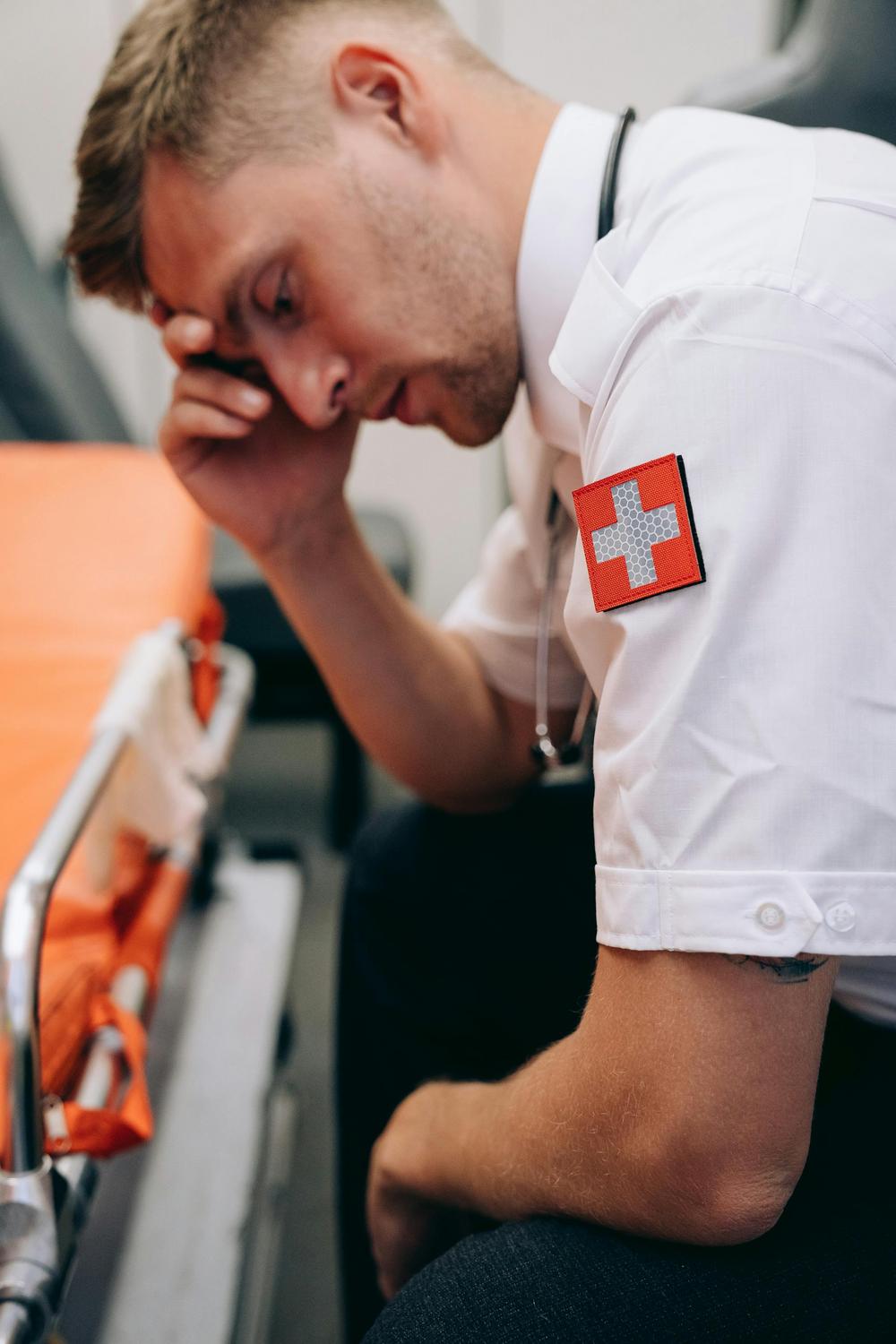

The Atlassian State of Teams Report established a clear correlation: more time spent in meetings correlates with higher burnout risk. When the average maker attends eight meetings weekly, combined with requisite refocus time, more than two hours per day evaporate from meaningful work capacity. Research indicates that healthcare professionals spend up to 37% of their time on non-productive activities, with frequent interruptions from administrative demands contributing substantially to the concerning statistic that 53% of physicians report burnout symptoms annually.

What Are the Practical Strategies for Implementing Maker Time?

Successfully operating on maker time requires deliberate architectural design of one’s schedule, supported by appropriate technological tools and organisational boundaries. The following evidence-based strategies enable healthcare professionals and consultants to protect the deep work necessary for delivering exceptional, personalised care:

Time Blocking and Task Batching

Dedicate substantial chunks of time—minimum two to four hours, ideally longer—to specific tasks requiring sustained concentration. Task batching proves particularly effective: group similar activities together rather than distributing them throughout the day. For instance, review multiple treatment plans consecutively rather than fragmenting this cognitive work across the week. Day theming represents an advanced implementation where specific days accommodate particular work types: administrative coordination on Mondays and Wednesdays, deep consulting work on Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Fridays.

Strategic Meeting Management

Batch meetings by type and day. Schedule all collaborative discussions within designated time blocks—preferably at day’s end when possible, following Paul Graham’s “office hours” approach. Never schedule meetings during peak creative and focus periods. Utilise “No Meetings Please” calendar blocks to communicate unavailability. Politely but firmly decline last-minute meeting requests during protected focus time. Research demonstrates that one company implementing protected focus time achieved a 35% increase in completion rates, 28% decrease in errors, and 45% improvement in team satisfaction.

Intelligent Calendar Planning

Schedule breaks strategically throughout the workday to maintain energy and cognitive resources. Include buffer time for unexpected issues rather than packing schedules tightly. Identify personal peak productivity periods—many professionals find morning hours optimal when willpower and cognitive resources remain highest—and reserve these for most demanding work. Share calendars with teams to communicate availability transparently, establishing clear boundaries between work and personal commitments.

Distraction Prevention Protocols

Disable non-essential notifications on all devices during focus blocks. Activate “Do Not Disturb” modes. Silence communication platforms including email and messaging applications. Create an organised, clutter-free workspace that supports concentration. Close unnecessary browser tabs and applications that tempt distraction. Noise-cancelling headphones can prove invaluable in shared workspaces.

Communication Boundaries and Expectations

Establish and communicate clear response time expectations for different channels: email responses within 24 hours, chat responses within four hours for non-urgent matters, direct messages within one hour for somewhat urgent issues, phone calls for truly urgent matters requiring immediate attention. Use asynchronous communication tools—email, recorded messages—instead of demanding immediate responses. Employ status indicators showing whether you’re available or in focus mode.

How Should Managers Structure Their Time Effectively?

Whilst maker time requires long, uninterrupted blocks, manager time benefits from different optimisation strategies that respect its fundamentally different operational requirements:

Establishing Regular Meeting Cadence

Determine optimal frequency and timing for recurring meetings. Schedule at consistent times (perhaps after lunch each day, or same day weekly for one-on-ones) to create predictability. Set clear agendas for all meetings, respecting time boundaries by starting and ending punctually. Make meetings meaningful and purposeful—never hold meetings without clear objectives or compelling reasons for attendees’ presence.

Communicating Availability Transparently

Explicitly communicate your schedule and availability patterns. Some managers open their calendars for employee slot booking; others implement “office hours” models where they announce availability via communication platforms. Signal availability status clearly in organisational tools. Make response time expectations transparent to prevent anxiety about unanswered communications.

Respecting Makers’ Schedule Needs

If your team includes makers, understanding their schedule requirements becomes a managerial responsibility. Avoid contacting makers during their designated focus time—they may feel organisationally obligated to respond immediately despite being mid-flow. Use asynchronous communication methods (project management tools, email) for non-urgent questions. Don’t interrupt makers during scheduled focus blocks. Schedule collaborative meetings away from times when makers need sustained concentration.

What Does This Mean for Australian Healthcare Consultancies?

For Australian healthcare consultancies operating in 2026—particularly those like CannElevate that emphasise personalised, bespoke approaches requiring deep thought and comprehensive planning—the maker-versus-manager framework proves especially relevant. AHPRA-registered professionals delivering sophisticated, stigma-free care must balance dual demands: the managerial coordination required for operational excellence and the deep, uninterrupted thinking necessary for developing truly personalised treatment strategies.

Healthcare professionals operating in consultancy environments require protected focus time for multiple critical activities: developing comprehensive treatment plans, conducting meaningful patient consultations, engaging in continuing professional education, and completing administrative documentation with appropriate thoroughness. The concept of “Deep Doctoring”—delivering optimal care through undivided attention—becomes impossible when schedules fragment into hourly slots punctuated by constant interruptions.

Research examining time management amongst health professionals in public hospital settings found that 66.1% demonstrated good time management practices. Notably, professionals effective at task planning were six times more likely to exhibit good overall time management. Highly responsible professionals showed 2.12 times greater likelihood of effective time management. Most significantly, professionals who actively minimised time-wasting activities were 86% more likely to demonstrate good time management—a finding that underscores the importance of protecting maker time from unnecessary interruptions.

The Perth-based healthcare sector, alongside broader Australian healthcare delivery, stands to benefit substantially from organisational recognition that supporting deep work through policy and culture—not merely individual effort—generates measurable improvements. When healthcare consultancies implement “meeting-free days” or “no-meeting times,” they effectively multiply available focus hours. Consider: freeing up three hours per professional per week across a consultancy of 50 professionals creates 150 additional focus hours weekly—equivalent to adding nearly four full-time professionals to deep work capacity without additional hiring costs.

Technology plays a crucial supporting role. Electronic health records, intelligent scheduling applications, and automation tools reduce administrative burden. Clear communication protocols prevent misunderstandings and wasted time. Virtual portals enable asynchronous patient communication, reducing interruption-driven workflow fragmentation.

However, technology alone cannot solve structural schedule mismatches. Organisational culture must evolve to recognise that the most powerful people—typically operating on manager schedules—possess positioning to impose their schedule type on everyone else. As Graham noted, “Smarter leaders restrain themselves” when they understand that makers need long chunks of uninterrupted time to deliver their best work.

The Path Forward: Integrating Both Schedule Types

The most sophisticated approach involves clearly distinguishing between maker and manager work modes whilst avoiding hourly alternation between them. Elon Musk exemplifies this integration: five-minute slots during manager mode, large uninterrupted chunks during maker mode. Paul Graham himself operates on two distinct workdays: programming from 3:00 AM until dinner (maker mode), business activities from dinner until 3:00 AM the following day (manager mode).

Academic Adam Grant provides another model: concentrating teaching commitments (manager mode) in autumn semester whilst dedicating spring and summer to research (maker mode). During research periods, he implements three-day blocks with out-of-office auto-responders, protecting extended focus time for deep scholarly work.

For Australian healthcare consultancies, this might translate to designating specific days for administrative coordination, team meetings, and collaborative planning (manager mode), whilst protecting other days entirely for treatment plan development, patient consultations requiring deep attention, and professional development activities (maker mode).

The critical insight remains unchanged from Graham’s original 2009 essay: neither schedule type proves inherently superior, and both remain essential for organisational success. Problems arise exclusively when these fundamentally incompatible schedule types collide without mutual understanding and deliberate structural accommodation.