What Are Neuroendocrine Stress Pathways and Why Do They Matter?

Neuroendocrine stress pathways constitute the integrated biological networks through which the nervous system and endocrine system communicate to maintain homeostasis during challenging conditions. These pathways represent the intersection of neurological signalling and hormonal regulation, creating a unified response system that adapts to environmental demands.

The term “neuroendocrine” itself illuminates this relationship: “neuro” refers to the nervous system’s rapid electrical signalling, whilst “endocrine” describes the hormonal messaging that provides sustained physiological changes. Together, these systems form three major interconnected pathways: the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis, the Sympathetic-Adrenal-Medullary (SAM) system, and the parasympathetic nervous system.

Understanding neuroendocrine responses proves essential for several compelling reasons. First, these pathways influence virtually every physiological system—from cardiovascular function to immune responses, metabolic regulation to cognitive performance. Second, dysregulation of stress pathways underlies numerous conditions affecting millions of Australians, including anxiety disorders, depression, cardiovascular disease, and metabolic syndrome. Third, recognising how these systems function empowers individuals and healthcare professionals to appreciate the profound mind-body connection that characterises human physiology.

The stress response operates through remarkably precise temporal dynamics. Within seconds, sympathetic activation triggers immediate physiological changes. Minutes later, hormonal cascades initiate metabolic adaptations. Hours afterward, regulatory feedback mechanisms restore equilibrium. This temporal choreography demonstrates biological engineering of extraordinary sophistication.

How Does the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) Axis Orchestrate Stress Responses?

The HPA axis functions as the body’s master stress regulator, serving as the principal neuroendocrine system controlling reactions to stress and regulating numerous physiological processes. This three-tiered structure operates through a precisely coordinated cascade mechanism that exemplifies biological feedback control.

The hypothalamus, situated at the base of the brain, contains specialised neurons within the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) that synthesise and release corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) and arginine vasopressin (AVP). These neurohormones travel through a specialised vascular network—the hypophysial portal system—directly to the anterior pituitary gland, avoiding dilution in general circulation.

Upon receiving CRH signals, the anterior pituitary responds by producing and secreting adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) into systemic circulation. Plasma ACTH levels typically peak within 15-20 minutes following stressor onset, demonstrating the rapidity of this hormonal communication. ACTH then travels to the adrenal glands, specifically targeting the zona fasciculata of the adrenal cortex.

Within the adrenal cortex, ACTH binds to melanocortin 2 receptors, stimulating the synthesis and release of glucocorticoids—primarily cortisol in humans. Glucocorticoid responses typically reach peak concentrations 30-60 minutes post-stressor, with standard stress response duration approximating two hours under normal circumstances.

Glucocorticoids exert profound metabolic effects: they mobilise glucose through gluconeogenesis, facilitate protein breakdown for amino acid availability, promote lipolysis for energy substrate provision, and modulate immune function. These hormones essentially redirect physiological resources towards immediate survival priorities, temporarily suppressing non-essential functions such as digestion, reproduction, and long-term immune surveillance.

The HPA axis demonstrates remarkable circadian regulation, with cortisol levels exhibiting approximately eight-fold higher concentrations in early morning (within one hour of waking) compared to midnight nadir. This circadian rhythmicity reflects the body’s anticipatory regulation, preparing physiological systems for daily activity demands before conscious awareness of waking.

| Stress Pathway | Activation Speed | Primary Mediators | Peak Response Time | Primary Functions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAM Axis | Seconds | Adrenaline, Noradrenaline | Immediate (0-30 seconds) | Cardiovascular activation, glucose mobilisation, heightened alertness |

| HPA Axis | Minutes | CRH, ACTH, Cortisol | 30-60 minutes | Metabolic adaptation, immune modulation, behavioural changes |

| endocannabinoid system | Minutes | Anandamide, 2-AG | Variable (5-30 minutes) | Stress buffering, feedback inhibition, emotional regulation |

| Parasympathetic System | Minutes to Hours | Acetylcholine | 30-120 minutes (recovery) | Restoration, energy conservation, homeostatic return |

What Role Do Neurotransmitters Play in Neuroendocrine Stress Regulation?

Neurotransmitters constitute the chemical messengers that enable communication between neurons and orchestrate the intricate signalling required for coordinated stress responses. Understanding neuroendocrine responses necessitates appreciating how these diverse neurotransmitter systems interact to modulate stress pathway activation.

Glutamate serves as the principal excitatory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system, providing essential synaptic drive to CRH-producing neurons in the PVN. During stress, glutamatergic transmission increases, enhancing neural excitation and promoting HPA axis activation. However, excessive glutamate under chronic stress conditions can induce neurotoxicity, contributing to neuronal damage in vulnerable brain regions.

Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) represents the major inhibitory neurotransmitter, accounting for approximately 40% of inhibitory brain processing. GABAergic neurons provide tonic inhibition to PVN CRH neurons, functioning as a biological brake on stress system activation. Reduced GABA signalling associates with hyperexcitability and anxiety manifestations. Paradoxically, chronic stress can transform GABA from inhibitory to excitatory through ion channel dysregulation, fundamentally altering neuronal responsiveness.

Noradrenaline (norepinephrine) originates primarily from the locus coeruleus in the brainstem, projecting throughout the nervous system. This catecholamine triggers alertness, focus, and arousal—essential components of the fight-or-flight response. Noradrenaline stimulates CRH neurons via α₁-adrenergic receptors, creating reciprocal activation between brainstem and hypothalamic stress centres. Dysregulation of noradrenergic systems links to numerous conditions affecting mood, attention, and stress responsiveness.

Serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine) regulates mood, sleep architecture, appetite, and emotional processing. This inhibitory neurotransmitter modulates both glutamate and dopamine transmission, creating complex interactive effects. Stress-induced serotonin dysregulation contributes to mood disturbances, with reduced serotonin levels correlating with depression, anxiety, and sleep disruption.

Dopamine governs motivation, reward processing, and motor control. Stress profoundly affects mesocorticolimbic reward circuits through dopamine modulation, with chronic stress reducing dopaminergic tone. This reduction contributes to anhedonia—the diminished capacity to experience pleasure—a hallmark feature of stress-related mood disorders.

These neurotransmitter systems do not operate in isolation. Serotonin inhibits dopamine release; dopamine modulates glutamate transmission; GABA regulates excitatory neurotransmission across multiple systems. Understanding neuroendocrine responses requires appreciating these complex interactions that create emergent properties beyond individual neurotransmitter functions.

How Does the Endocannabinoid System Buffer Neuroendocrine Stress Responses?

The endocannabinoid system represents a fundamental stress-buffering network essential for maintaining physiological homeostasis. This endogenous biological system, present in all mammals, consists of lipid-based signalling molecules produced on-demand by neurons to fine-tune neurotransmission and regulate stress pathway activation.

Two primary endocannabinoid molecules mediate stress regulation: anandamide (AEA) and 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG). Unlike conventional neurotransmitters that operate through forward signalling (presynaptic to postsynaptic), endocannabinoids function as retrograde messengers—synthesised by postsynaptic neurons and travelling backward to bind receptors on presynaptic terminals.

Cannabinoid receptor type 1 (CB₁) exhibits high expression throughout the central nervous system, particularly in brain regions governing stress responses, emotional processing, and memory formation. CB₂ receptors localise primarily to peripheral tissues and immune cells, though emerging research identifies functional CB₂ in specific brain regions.

The endocannabinoid system exerts critical regulatory functions in neuroendocrine stress pathways. It inhibits excessive glutamate and GABA release, preventing runaway excitation or inhibition. It regulates HPA axis activation and termination, mediating glucocorticoid-induced negative feedback. It facilitates fear extinction—the process by which learned fear responses diminish over time—and modulates emotional memory processing.

Stress profoundly affects endocannabinoid signalling. Acute stress decreases anandamide levels in the amygdala through increased enzymatic degradation, potentially contributing to anxiety and fear responses. Conversely, glucocorticoids elevate 2-AG synthesis in the PVN, contributing to rapid feedback inhibition of HPA axis activity. Enhanced 2-AG signalling in the basolateral amygdala during repeated stress supports HPA habituation—the process by which stress responses diminish with repeated exposure to the same stressor.

The molecular mechanism underlying endocannabinoid-mediated feedback demonstrates biological elegance. Glucocorticoids activate membrane-associated receptors, triggering rapid (non-genomic) endocannabinoid synthesis within minutes. These endocannabinoids bind CB₁ receptors on presynaptic terminals containing glutamatergic neurons that project to CRH-producing cells. This binding suppresses glutamate release, reducing excitatory drive to CRH neurons and dampening HPA axis activation. This mechanism enables rapid glucocorticoid feedback inhibition independent of slower transcriptional processes.

Chronic stress disrupts endocannabinoid homeostasis. Prolonged stress exposure reduces CB₁ receptor expression and impairs endocannabinoid synthesis, compromising this critical stress-buffering system. This dysregulation may contribute to stress-related conditions characterised by impaired fear extinction, excessive anxiety, and inadequate stress recovery.

How Do Brain Regions Integrate to Create Coordinated Neuroendocrine Stress Responses?

Understanding neuroendocrine responses requires appreciating the neural circuitry connecting diverse brain regions into functional networks. The stress response emerges not from isolated brain structures but from coordinated activity across interconnected regions that process sensory information, emotional significance, contextual memory, and physiological regulation.

The amygdala serves as the brain’s emotional processing centre, evaluating threat significance and emotional salience. Different amygdalar nuclei preferentially respond to distinct stressor types: the central nucleus activates during physiological stressors (pain, hypotension, inflammation), whilst the medial nucleus responds to emotional and social stressors. The basolateral amygdala integrates sensory information with emotional significance, projecting to numerous stress-responsive regions. Chronic stress induces amygdalar hypertrophy—dendritic expansion and increased spine density—enhancing emotional reactivity and fear responses.

The hippocampus contributes critical functions in memory formation, contextual processing, and stress regulation. This structure inhibits excessive HPA axis activation, providing top-down restraint on stress responses. The hippocampus contains exceptionally high densities of glucocorticoid receptors (GR) and mineralocorticoid receptors (MR), enabling sensitive detection of circulating stress hormones. Ventral hippocampal regions primarily govern stress regulation, whilst dorsal regions mediate cognitive functions. Hippocampal atrophy represents a hallmark feature of chronic stress exposure and stress-related conditions, with volume reductions correlating with memory impairments and fear generalisation.

The prefrontal cortex executes executive functions and provides sophisticated cognitive modulation of stress responses through top-down inhibition. The medial prefrontal cortex regulates HPA axis activity, with the prelimbic cortex inhibiting responses to psychological stressors. This region projects glutamatergic inputs to GABAergic neurons in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST), which in turn projects to the PVN. Chronic stress reduces prefrontal cortex volume and connectivity, impairing executive control over emotional responses and weakening top-down regulation of the amygdala.

The bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST) integrates limbic and hypothalamic inputs, functioning as a relay station between cortical/limbic structures and the PVN. The anterior BNST activates during acute stress excitation, whilst the posterior BNST mediates stress inhibition. GABAergic neurotransmission within the BNST proves essential for regulating PVN CRH neuron activity.

The nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) in the brainstem receives visceral sensory information from the vagus nerve and sympathetic nervous system. A2/C2 noradrenergic cell groups within the NTS preferentially innervate CRH-producing PVN neurons, mediating rapid HPA axis responses to homeostatic perturbations such as hypotension, inflammatory challenges, and pain. The NTS provides direct glutamatergic and noradrenergic projections to the PVN, enabling swift responses to physiological threats.

The locus coeruleus contains the brain’s largest cluster of noradrenergic neurons, projecting throughout the neuroaxis. This structure maintains reciprocal connections with PVN CRH neurons, creating a positive feedback loop: CRH activates locus coeruleus noradrenergic neurons, and noradrenaline stimulates CRH neurons via α₁-adrenergic receptors. This reciprocal activation coordinates stress responses across diverse brain regions.

These regions do not function independently but form integrated networks. Psychological stressors require multi-synaptic pathways involving limbic structures, necessitating integration of mnemonic (memory-based) and sensory information. Physical stressors activate more direct brainstem pathways, bypassing extensive limbic processing. This circuit architecture enables stressor-specific responses whilst maintaining system-wide coordination.

What Feedback Mechanisms Regulate Neuroendocrine Stress Pathway Termination?

The capacity to terminate stress responses proves equally critical to initiating them. Proper HPA axis shutdown prevents pathological hyperactivation and maintains metabolic homeostasis. Glucocorticoid-mediated negative feedback represents the primary mechanism enabling stress response termination, operating through multiple temporal scales and anatomical sites.

Fast feedback occurs within minutes through non-genomic mechanisms. Glucocorticoids bind membrane-associated receptors, rapidly triggering endocannabinoid synthesis and release in the PVN. These endocannabinoids suppress glutamatergic inputs to CRH neurons, dampening HPA activation independent of gene transcription. This mechanism, mediated by Gs-cAMP/protein kinase A pathways, enables swift response modulation.

Intermediate feedback operates over hours, involving glucocorticoid effects on the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex. These brain regions contain abundant glucocorticoid receptors, enabling sensitive detection of circulating cortisol. Glucocorticoid binding modulates GABAergic neurons in the BNST and hypothalamus that project to the PVN, enhancing inhibitory tone. Hippocampal glucocorticoid receptor-mediated inhibition of limbic outputs to the PVN regulates both stress response magnitude and duration.

Delayed feedback requires hours, operating through genomic mechanisms. Glucocorticoids bind nuclear mineralocorticoid receptors (MR) and glucocorticoid receptors (GR), functioning as ligand-gated transcription factors. These activated receptors translocate to cell nuclei, binding specific DNA sequences and altering gene expression of CRH, ACTH, and steroidogenic enzymes. This transcriptional regulation modifies the HPA axis’s functional capacity over extended timeframes.

Mineralocorticoid receptors exhibit higher glucocorticoid affinity than GR, binding cortisol at basal concentrations. High MR expression in the hippocampus enables these receptors to regulate basal circadian and ultradian HPA rhythms, dictating HPA axis activity relative to time of day. MR activation supports stress resilience and adaptive responses.

Glucocorticoid receptors activate primarily during elevated glucocorticoid states characteristic of stress. Abundant GR expression in the PVN, hippocampus, prefrontal cortex, and amygdala enables widespread feedback regulation. GR mediates glucocorticoid effects on energy mobilisation, inflammation, and neural function. The ratio of MR to GR influences stress-induced HPA axis activity, with optimal ratios promoting resilience.

Chronic stress disrupts these elegant feedback mechanisms. Prolonged glucocorticoid exposure downregulates GR expression in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex, impairing negative feedback efficacy. This glucocorticoid resistance perpetuates HPA activation despite elevated cortisol levels, creating a pathological state where regulatory mechanisms fail. Impaired feedback contributes to sustained HPA hyperactivity characteristic of depression and anxiety disorders, or paradoxical HPA hyporesponsiveness observed in some chronic stress conditions.

What Are the Long-Term Consequences of Chronic Neuroendocrine Stress Pathway Activation?

Whilst acute stress responses represent adaptive physiological mechanisms, chronic or repeated activation transforms protective systems into pathological processes. The concept of allostatic load describes cumulative physiological wear-and-tear resulting from prolonged allostasis—the active maintenance of homeostasis through physiological adaptation.

Chronic HPA axis hyperactivity manifests through elevated basal glucocorticoid secretion, particularly at circadian nadir when cortisol should reach lowest levels. Delayed stress response termination, blunted negative feedback efficacy, and persistent CRH elevation characterise this state. Enhanced adrenal sensitivity to ACTH develops, with adrenal hypertrophy and hyperplasia representing morphological consequences. Paradoxically, some individuals develop HPA hyporesponsiveness following prolonged stress—reduced ACTH and cortisol responses despite chronic stressor presence, representing a “burned out” stress system.

Chronic stress profoundly affects brain structure and function. In the hippocampus, dendritic retraction, reduced spine density, and decreased neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus occur. Hippocampal volume reductions correlate with impaired memory consolidation and fear extinction learning deficits. The prefrontal cortex undergoes dendritic remodeling and atrophy, with reduced branching compromising executive functions and weakening top-down control of the amygdala. Conversely, the amygdala exhibits dendritic expansion and increased spine density, enhancing emotional reactivity and fear generalisation.

Cardiovascular consequences prove substantial. Chronic stress induces sustained hypertension through persistent sympathetic activation. Stress-induced catecholamine surges and cortisol elevation promote atherosclerosis development via endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and inflammatory mechanisms. Increased myocardial infarction, stroke, and arrhythmia risk represents clinical manifestations. Dyslipidemia from altered lipid metabolism further compounds cardiovascular risk.

Metabolic dysregulation emerges through insulin resistance development, metabolic syndrome progression, and increased type 2 diabetes risk. Central obesity—preferential visceral fat deposition—characterises chronic stress exposure. Altered appetite regulation through modified ghrelin (hunger hormone) and leptin (satiety hormone) signalling contributes to weight gain and metabolic complications.

Immune system modulation shifts from acute pro-inflammatory responses followed by anti-inflammatory cortisol effects, to chronic glucocorticoid resistance and persistent inflammation. Reduced lymphocyte counts and function increase infection susceptibility. Delayed wound healing and immune-endocrine feedback loop disruption via cytokine-HPA interactions perpetuate inflammatory states. The glucocorticoid resistance characteristic of chronic stress means that despite elevated cortisol, anti-inflammatory effects diminish, allowing unchecked inflammatory signalling.

Reproductive function suffers as CRH inhibits gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), suppressing luteinising hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). Stress-induced hypothalamic amenorrhea particularly affects women, whilst men experience decreased testosterone, impaired erectile function, and reduced sperm quality. Inhibition of gonadal steroidogenesis represents the molecular mechanism underlying reproductive suppression.

Oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction amplify chronic stress pathology. Mitochondria represent primary cellular sources of reactive oxygen species (ROS), with chronic stress increasing ROS production through altered electron transport chain function. Oxidative damage to lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids—including mitochondrial DNA—reduces ATP production and triggers apoptosis. Neuroinflammation perpetuation and neurodegeneration in vulnerable brain regions links chronic stress to neurodegenerative conditions.

The Integration of Stress Systems: A Unified Biological Response

Modern neuroscience reveals that understanding neuroendocrine responses requires viewing stress pathways not as isolated systems but as seamlessly integrated networks. The SAM axis provides immediate physiological mobilisation within seconds. The HPA axis delivers secondary metabolic and behavioural adaptation over minutes to hours. The parasympathetic nervous system facilitates recovery and restoration. Overlapping activation periods create cumulative adaptive responses greater than the sum of individual components.

The PVN serves as the central integrative hub, receiving diverse inputs from limbic structures conveying emotional and contextual information, brainstem regions relaying visceral and sensory data, and circadian timing centres encoding temporal parameters. The distributed endocannabinoid system fine-tunes signalling at all levels, providing moment-to-moment regulation of excitatory and inhibitory balance.

Multiple feedback loops operate simultaneously across hierarchical levels with parallel processing. Cross-talk between HPA and SAM systems ensures coordinated responses. Circadian timing mechanisms override immediate demands when appropriate. Adaptive learning from repeated stress exposure—termed habituation—demonstrates the system’s capacity for experience-dependent modification.

Advancing Our Understanding of Stress Biology in 2026

The year 2026 witnesses unprecedented advancement in stress pathway research, with Australian contributions to neuroscience yielding profound insights. AHPRA-registered health practitioners increasingly recognise the fundamental importance of understanding neuroendocrine responses for comprehensive patient care. The integration of stress pathway knowledge into clinical practice represents a paradigm shift from symptom management to mechanistic understanding.

Research continues illuminating the intricate molecular mechanisms governing stress system regulation, feedback inhibition, and chronic dysregulation. Epigenetic modifications—alterations in gene expression without DNA sequence changes—emerge as critical mediators of early life stress effects that persist into adulthood. Understanding these mechanisms offers potential avenues for intervention and resilience enhancement.

The recognition that stress-related conditions affect millions of Australians underscores the public health significance of understanding neuroendocrine responses. Major depressive disorder affects approximately one in six individuals, with anxiety disorders representing the most prevalent mental health conditions. The limited remission rates with conventional approaches highlight the need for innovative, mechanistically-informed strategies.

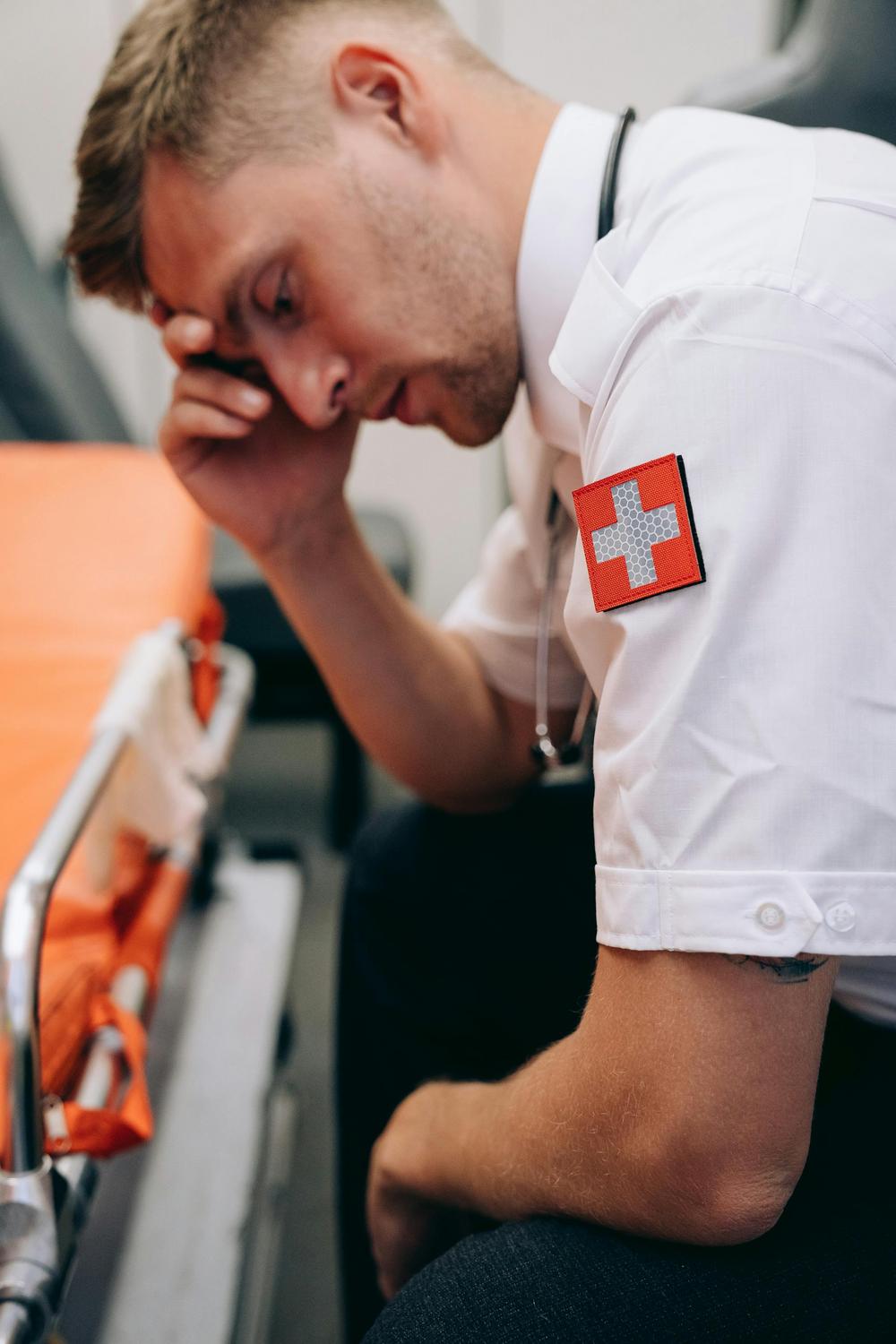

Healthcare practitioners operating within Australia’s sophisticated regulatory framework—overseen by AHPRA and the Medical Board of Australia—bear responsibility for maintaining current knowledge of stress pathway biology. The Code of Conduct emphasises practitioner wellbeing, recognising that healthcare workers themselves face substantial occupational stress. Understanding neuroendocrine stress pathways proves essential not only for patient care but for practitioner self-awareness and resilience.

The convergence of neuroscience, endocrinology, and clinical practice creates opportunities for holistic approaches addressing stress-related conditions. Recognising that stress responses involve integrated biological systems spanning the nervous system, endocrine system, immune system, and metabolic regulation enables comprehensive care strategies. The move toward precision wellness—tailored approaches based on individual stress pathway characteristics—represents the future of stress-related healthcare.

How quickly do neuroendocrine stress pathways activate following stressor exposure?

Neuroendocrine stress pathways activate across multiple temporal scales. The sympathetic-adrenal-medullary (SAM) system responds within seconds, releasing adrenaline and noradrenaline for immediate changes, while the HPA axis is activated within minutes—with CRH released within 0-5 minutes, ACTH peaking at 15-20 minutes, and cortisol reaching maximum levels at 30-60 minutes post-stressor.

What distinguishes acute stress responses from chronic stress pathway dysregulation?

Acute stress responses are time-limited and proportionate adaptations that typically resolve within a couple of hours via effective negative feedback. In contrast, chronic stress pathway dysregulation involves prolonged or repetitive activation that overwhelms regulatory mechanisms, leading to altered basal hormone levels, impaired feedback, structural brain changes, and widespread systemic effects.

How does the endocannabinoid system influence stress pathway regulation?

The endocannabinoid system acts as a stress-buffering network by producing molecules like anandamide and 2-AG that serve as retrograde messengers. These molecules bind to CB₁ receptors to inhibit excessive neurotransmitter release, contribute to rapid glucocorticoid feedback inhibition of the HPA axis, facilitate fear extinction, and help modulate emotional responses.

Why do individuals exhibit different stress pathway responses to identical stressors?

Individual variability in stress responses is influenced by genetic factors, early life experiences, epigenetic modifications, and current environmental contexts. Differences in receptor expression, neurotransmitter function, and hormonal regulation all contribute to why the same stressor can result in different physiological and emotional outcomes among individuals.

What role does circadian rhythm play in neuroendocrine stress pathway function?

Circadian rhythms are crucial in regulating neuroendocrine stress responses. The suprachiasmatic nucleus, as the body’s master clock, coordinates fluctuations in cortisol levels—typically peaking in the early morning and declining at night—ensuring that stress responses are appropriately timed relative to daily activity and rest. Disruption of this rhythm can exacerbate stress-related conditions.