You close your laptop after a long day, yet your mind refuses to switch off. That half-finished report, the email you meant to send, the project sitting at 85% completion—they circle relentlessly through your thoughts, stealing your sleep and fragmenting your focus. This isn’t poor discipline or overwork alone. You’re experiencing a well-documented psychological phenomenon that has captivated researchers for nearly a century: the Zeigarnik Effect.

First documented in 1927 by Lithuanian-Soviet psychologist Bluma Zeigarnik at the University of Berlin, this cognitive quirk reveals a fundamental truth about human memory and motivation. Our brains don’t simply file away incomplete tasks—they actively prioritise them, creating persistent mental loops that demand resolution. Understanding this effect isn’t merely academic curiosity; it’s essential knowledge for anyone seeking to optimise their cognitive performance, reduce stress, and reclaim mental clarity in an age of constant interruption.

What Is the Zeigarnik Effect and Why Does It Dominate Your Thoughts?

The Zeigarnik Effect describes our remarkable tendency to remember unfinished or interrupted tasks significantly better than completed ones. In her groundbreaking research, Zeigarnik discovered that participants recalled interrupted tasks approximately 90% better than those they’d completed—a finding that would fundamentally reshape our understanding of memory and motivation.

The phenomenon emerged from an everyday observation. Zeigarnik’s mentor, Kurt Lewin, noticed that restaurant waiters possessed extraordinary recall for unpaid orders but immediately forgot them once customers settled their bills. This casual observation prompted rigorous experimentation that would validate a crucial insight: task-specific psychological tension persists during incomplete work but dissipates upon completion.

Zeigarnik’s experiments involved 32 adults performing 15-22 diverse tasks—threading needles, solving mathematical problems, constructing paper boxes, drawing figures. Crucially, researchers interrupted participants midway through randomly selected tasks. After an hour’s delay, participants demonstrated dramatically superior recall of interrupted versus completed activities. The effect proved remarkably consistent across 138 children tested in group settings, with 80% retention for interrupted tasks compared to just 12% for completed ones.

This cognitive phenomenon operates through several interconnected mechanisms. According to Lewin’s field theory and Gestalt psychology principles, each initiated task creates measurable psychological tension that enhances cognitive accessibility. This tension establishes what researchers term “open loops” in working memory—active mental representations that the brain continuously prioritises for resolution. The incomplete pattern violates our fundamental psychological drive towards closure, generating persistent mental reminders that keep unfinished work perpetually salient in consciousness.

How Does the Zeigarnik Effect Actually Work in Your Brain?

The neurobiological architecture underlying the Zeigarnik Effect reveals why unfinished tasks possess such extraordinary mental persistence. Your brain doesn’t passively store incomplete work; it actively allocates substantial working memory resources to maintain detailed task representations, consuming finite cognitive bandwidth that might otherwise support new learning, creative problem-solving, or simple relaxation.

When you begin any task, your brain establishes dedicated neural pathways that remain partially activated until completion signals their dissolution. These pathways create what neuroscientists describe as elevated cognitive accessibility—the incomplete task remains more readily retrievable and occupies heightened priority in your attentional hierarchy. This biological reality explains why that unfinished presentation intrudes during dinner conversations or why incomplete errands surface during meditation practice.

The effect engages your brain’s reward circuitry in fascinating ways. Task completion triggers dopamine release—the neurotransmitter fundamentally associated with motivation, pleasure, and reinforcement. This neurochemical reward creates positive feedback loops, encouraging future task completion whilst simultaneously making incomplete work psychologically uncomfortable. Your brain essentially holds open accounts for unfinished business, maintaining low-grade activation of stress response systems until closure provides neurochemical resolution.

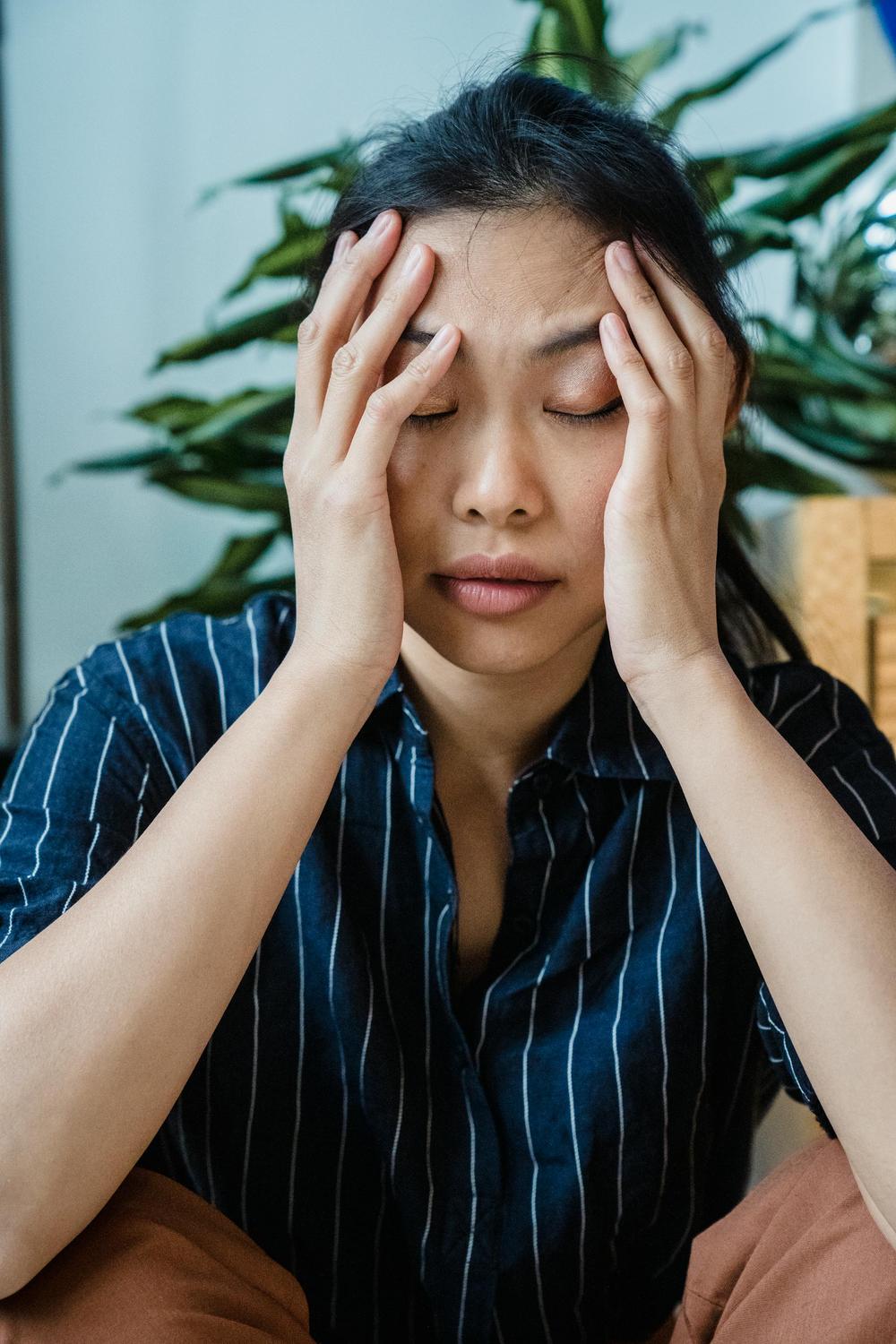

Research by Syrek and colleagues (2017), published in the Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, demonstrated tangible consequences of this persistent activation. Their 12-week study tracking 59 employees across 357 observations revealed that unfinished tasks at week’s end significantly impaired weekend sleep quality through affective rumination. The mechanism proved clear: incomplete work maintained elevated cortisol levels and prevented the physiological down-regulation necessary for restorative sleep. Notably, the effect intensified with accumulation—unfinished tasks persisting across three months created greater sleep disruption than acute incompletions.

Can the Zeigarnik Effect Actually Improve Your Performance?

Whilst unfinished tasks often generate stress and mental fatigue, the Zeigarnik Effect possesses remarkable potential for strategic application. The same cognitive mechanisms that create intrusive thoughts can enhance memory consolidation, boost motivation, and optimise learning when deliberately leveraged.

The memory enhancement dimension proves particularly valuable for educational contexts. Students who study material in interrupted sessions—pausing before complete mastery—demonstrate superior long-term retention compared to those achieving immediate closure. The lingering psychological tension maintains active mental engagement with content between study sessions, facilitating deeper encoding and more robust memory formation. This contradicts conventional wisdom suggesting comprehensive completion before breaks, revealing that strategic incompletion can strengthen rather than weaken learning outcomes.

Task interruption timing significantly moderates these effects. Zeigarnik’s research demonstrated that tasks interrupted near completion or midway through generated stronger recall than those interrupted shortly after initiation. This suggests that psychological investment—how much mental and emotional capital you’ve allocated—determines the effect’s magnitude. The closer you approach completion before interruption, the more powerful the cognitive tension becomes.

Individual differences profoundly shape how the Zeigarnik Effect manifests. Research by Atkinson (1953) established that high-achievement individuals experience significantly stronger effects than average-ambition participants. Those viewing incomplete tasks as personal failures rather than neutral interruptions showed heightened recall disparities between finished and unfinished work. This reveals that personality characteristics—particularly conscientiousness, perfectionism, and achievement orientation—fundamentally moderate whether the effect becomes motivating fuel or anxiety-producing burden.

What Strategies Actually Harness the Zeigarnik Effect for Productivity?

Translating psychological theory into practical application requires sophisticated understanding of how to manage the tension between leveraging incomplete tasks for motivation whilst preventing cognitive overload. Research-validated strategies offer frameworks for achieving this delicate balance.

Externalisation remains paramount. Your brain maintains heightened vigilance for unfinished tasks partly because it fears forgetting crucial commitments. Creating trusted external systems—whether physical notebooks, digital task managers, or structured planning documents—provides what psychologists term “permission to forget.” When you reliably capture tasks in external repositories, your mind reduces background monitoring, freeing cognitive resources for focused work. Research demonstrates that simply writing down unfinished tasks significantly reduces their intrusive presence, even without immediate completion.

Strategic task initiation leverages both the Zeigarnik Effect and the related Ovsiankina Effect—the motivation to complete previously initiated work. Beginning tasks, even incompletely, creates psychological momentum that enhances completion likelihood. The “10-minute rule” exemplifies this principle: commit to just 10 minutes of work on avoided tasks. Once started, the Zeigarnik Effect’s psychological tension often sustains effort beyond initial intentions. This directly counters procrastination by converting avoidance into engagement through minimal initial commitment.

Creating micro-completions prevents overwhelming accumulation of open loops. Large projects generate substantial psychological burden when treated as single, monolithic tasks. Breaking complex work into smaller, independently completable segments provides regular closure experiences whilst maintaining forward progress. Each micro-completion delivers neurochemical reward through dopamine release, building motivation whilst preventing the cognitive overload that occurs when multiple large-scale projects remain simultaneously unfinished.

Contemporary research by Baumeister and Masicampo (2011) revealed that creating plans provides cognitive closure effects remarkably similar to actual completion. Simply scheduling unfinished tasks—designating specific times and contexts for their continuation—reduces their background cognitive interference. This suggests that the brain seeks assurance of eventual completion rather than immediate resolution. A trusted plan satisfies this requirement, allowing mental resources to shift elsewhere.

How Do Unfinished Tasks Impact Your Wellbeing and Mental Health?

The psychological costs of accumulated incomplete work extend far beyond simple distraction. Modern knowledge work environments, characterised by constant interruption and simultaneous project demands, create conditions where the Zeigarnik Effect transforms from occasional nuisance into chronic wellbeing threat.

Research by Gloria Mark at the University of California, Irvine, quantifies interruption costs with sobering precision. After task interruption, people require an average of 23 minutes and 15 seconds to return to their original work with equivalent focus. Email interruptions alone—averaging 96 daily occurrences for typical knowledge workers—consume approximately 1.5 hours through cumulative reorientation time. Each interruption potentially triggers the Zeigarnik Effect, leaving psychological residue that fragments attention and depletes mental energy.

The sleep disruption documented by Syrek and colleagues represents particularly concerning territory. Quality sleep forms the foundation for immune function, emotional regulation, cognitive performance, and physical health. When unfinished work infiltrates rest periods through rumination, it undermines recovery mechanisms essential for sustained wellbeing. The study’s finding that three-month accumulations create greater impairment than acute incompletions suggests a cumulative toxicity to perpetual incompletion.

Chronic exposure to multiple simultaneous open loops generates measurable cognitive burden. Research indicates that maintaining four or more concurrent unfinished tasks significantly increases cognitive load whilst reducing available willpower for subsequent decision-making and self-regulation. This depletion manifests as increased stress reactivity, diminished emotional resilience, and reduced capacity for complex problem-solving—consequences that ripple across both professional and personal domains.

However, understanding the Zeigarnik Effect also illuminates pathways towards enhanced wellbeing. Implementing deliberate completion practices—addressing unfinished tasks before transitioning to rest periods, establishing clear stopping points at natural milestones, creating celebratory rituals for task closure—provides psychological protection against rumination whilst delivering neurochemical rewards that build positive momentum.

Why Do Some People Experience the Zeigarnik Effect More Intensely?

The universality of the Zeigarnik Effect belies substantial individual variation in its manifestation and impact. Personality architecture, motivational frameworks, and broader psychological patterns fundamentally moderate whether incomplete tasks generate primarily motivation or primarily anxiety.

Research consistently demonstrates that the effect intensifies with ego-involvement and achievement orientation. When tasks connect meaningfully to personal identity, values, or professional reputation, incompletion creates heightened psychological tension. High-achievers and perfectionists often experience the Zeigarnik Effect as particularly burdensome, with unfinished work triggering harsh self-evaluation rather than simple motivational pressure. This creates paradoxical situations where conscientiousness—typically protective for productivity—becomes a vulnerability through excessive cognitive rumination.

The concept of “need for cognitive closure” (NCC) provides additional explanatory framework. Individuals high in NCC demonstrate strong preference for definitive answers over ambiguity, order over chaos, and completion over openness. Research by White (2021) found that college students with elevated NCC experienced significantly greater stress and anxiety during COVID-19 pandemic uncertainty. Applied to the Zeigarnik Effect, high-NCC individuals likely experience incomplete tasks as particularly aversive, potentially triggering anxiety responses disproportionate to actual task significance.

Cultural factors introduce further complexity. Societies emphasising collective responsibility, perfectionism, or rigid work-life boundaries may amplify or attenuate the effect’s impact. Task completion norms vary substantially across cultures, influencing whether incompletion generates shame, neutral acknowledgement, or even positive recognition of thoughtful deliberation.

These individual differences underscore the necessity for personalised approaches. Whilst some individuals harness the Zeigarnik Effect’s motivational pressure effectively, others require deliberate cognitive strategies—self-compassion practices, explicit task boundaries, permission-granting frameworks—to prevent accumulated incompletions from undermining wellbeing.

Beyond Simple Memory: The Zeigarnik Effect as Mental Architecture

The Zeigarnik Effect reveals far more than a peculiarity of human memory—it exposes fundamental architecture of how consciousness manages goals, allocates attention, and constructs meaning from experience. Nearly a century after Zeigarnik’s initial observations, this phenomenon continues generating insights across psychology, neuroscience, and applied performance optimisation.

The effect’s persistence across diverse contexts and populations validates core principles from Gestalt psychology: humans possess an innate drive towards completion, pattern closure, and psychological resolution. Incomplete tasks violate this fundamental orientation, creating tension that commands cognitive resources until satisfaction. This isn’t dysfunction but rather a sophisticated adaptation—our ancestors survived partly through remembering unfinished survival tasks with greater fidelity than completed ones.

Contemporary application demands nuanced understanding. The digital age has exponentially multiplied potential sources of incompletion—partial emails, abandoned browser tabs, initiated but incomplete online profiles, interrupted video consumption. Each represents a micro-instance of the Zeigarnik Effect, collectively creating unprecedented cognitive burden. Successfully navigating modern complexity requires deliberate practices: ruthless prioritisation of genuinely important incompletions, systematic externalisation of task management, strategic use of planning for cognitive closure, and cultivation of self-compassion regarding inevitable incompletion in environments of infinite possibility.

The sleep research by Syrek and colleagues perhaps most powerfully illustrates practical stakes. When professional incompletion infiltrates personal recovery time, it threatens foundational wellbeing mechanisms. Implementing weekend task closure—even partial completion or robust planning—protects rest quality whilst modelling healthy work-life integration. This practice acknowledges psychological reality rather than denying it, working with the Zeigarnik Effect rather than against it.

Moving forward, understanding this phenomenon empowers more conscious choices about task initiation, strategic incompletion for memory enhancement, deliberate completion practices for wellbeing protection, and personalised approaches reflecting individual psychological architecture. The Zeigarnik Effect isn’t a problem to eliminate but rather a cognitive feature to understand, respect, and leverage strategically.

What is the Zeigarnik Effect in simple terms?

The Zeigarnik Effect is the psychological tendency to remember unfinished or interrupted tasks better than completed ones. It occurs because incomplete tasks create persistent psychological tension that keeps them mentally active until resolution.

How can I use the Zeigarnik Effect to overcome procrastination?

Leverage the Zeigarnik Effect by simply starting tasks, even incompletely. Committing to just 10 minutes of work on avoided projects can create the psychological momentum needed to overcome procrastination, transforming avoidance into engagement.

Does the Zeigarnik Effect cause sleep problems?

Yes, research demonstrates that unfinished tasks can impair sleep quality. Incomplete work often leads to rumination, which keeps stress hormones elevated and interferes with the physiological processes needed for restorative sleep.

Why don’t I experience the Zeigarnik Effect for all unfinished tasks?

Individual variation plays a significant role. Tasks that are personally important, ego-involving, or tied to your identity trigger a stronger effect. Personality traits such as conscientiousness and perfectionism also influence whether the effect primarily motivates or causes anxiety.

Can writing down tasks really reduce the Zeigarnik Effect’s mental burden?

Yes. Externalizing tasks by writing them down in notebooks or digital task managers helps to offload the cognitive load, giving your brain ‘permission to forget’ and reducing the mental persistence of unfinished tasks.