Waking with the terrifying sensation of being completely unable to move, fully conscious yet trapped within one’s own body, whilst a shadowy presence looms nearby – this is the reality for approximately 8 in every 100 Australians who experience sleep paralysis. Far from being a rare or supernatural occurrence, sleep paralysis represents a fascinating intersection of neuroscience, sleep medicine, and human consciousness that affects nearly one-third of the global population at some point in their lives. Despite its prevalence and the profound distress it can cause, this phenomenon remains widely misunderstood, often leaving individuals searching for answers in a landscape cluttered with misconceptions and fear-based narratives.

What Is Sleep Paralysis and Why Does It Occur?

Sleep paralysis is a temporary state where consciousness and involuntary muscle paralysis coexist during transitions between sleep and wakefulness. During these episodes, individuals maintain complete awareness of their surroundings whilst being unable to move their body or speak, typically lasting from several seconds to approximately six minutes. This phenomenon represents what sleep researchers describe as a “mixed state of consciousness” – a dissociative condition where the brain’s waking state overlaps with characteristics of REM (Rapid Eye Movement) sleep.

The mechanism underlying sleep paralysis centres on the disruption of normal REM sleep processes. During typical REM sleep, the brain enters a highly active state generating vivid dreams whilst simultaneously initiating muscle atonia – a protective temporary paralysis preventing individuals from physically acting out their dreams. Sleep paralysis occurs when this protective paralysis persists into wakefulness, or conversely, when consciousness emerges before the paralysis has dissipated. The result is a state where individuals experience full sensory awareness and cognitive function whilst remaining physically immobilised.

Research has identified that sleep paralysis involves a neural imbalance where cholinergic sleep “on” populations become hyperactivated whilst serotonergic sleep “off” populations become under-activated. Additionally, the brain’s threat-activated vigilance system often becomes engaged during episodes, contributing to the intense fear response many individuals experience. Twin studies have further suggested a genetic predisposition, as monozygotic twins exhibit high concordance rates for this condition.

Who Experiences Sleep Paralysis Most Frequently?

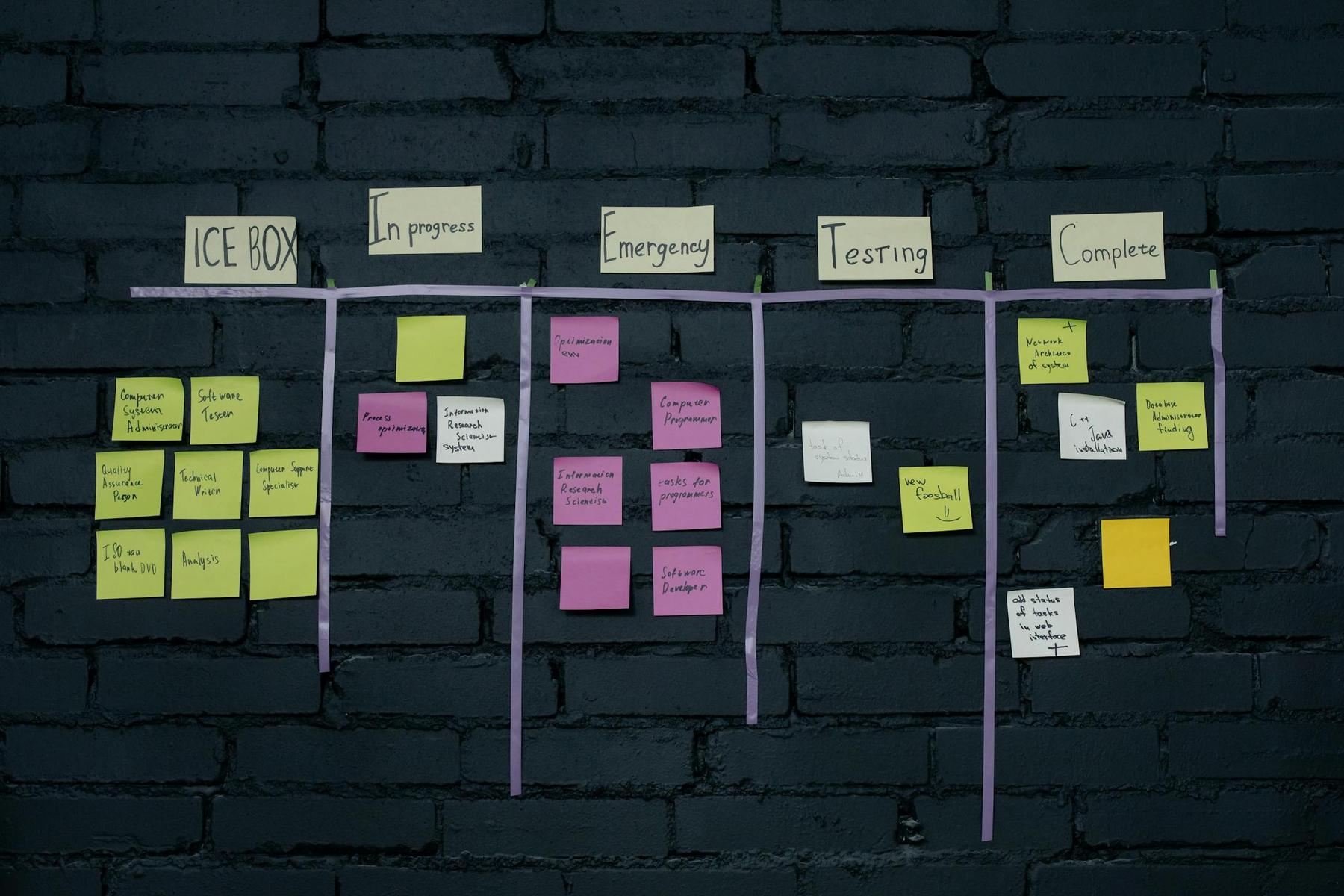

Global research indicates that sleep paralysis affects roughly 30% of the population when data from all demographic groups are combined, though prevalence varies. Psychiatric patients, for example, have a notably higher risk with 35% reporting episodes, and students similarly report high rates, likely due to academic stress and irregular sleep patterns. Studies have shown that sleep paralysis is especially common among individuals with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and panic disorder, and research demonstrates that episodes most often begin in adolescence or early adulthood.

| Population Group | Prevalence Rate | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| General Population | 7.6% lifetime | Baseline prevalence across all ages |

| Psychiatric Patients | 35% | High risk associated with anxiety/mood disorders |

| Students | 34% | Academic stress and irregular sleep patterns |

| PTSD Patients | 60% | Fragmented REM sleep and autonomic dysregulation |

| Medical Students | 52.4% lifetime | High stress, sleep deprivation; 15% weekly episodes |

| Panic Disorder | 34.6% | Heightened anxiety sensitivity |

Ethnicity also plays a role, with minority populations often exhibiting higher rates compared to Caucasian groups.

What Do Sleep Paralysis Episodes Actually Feel Like?

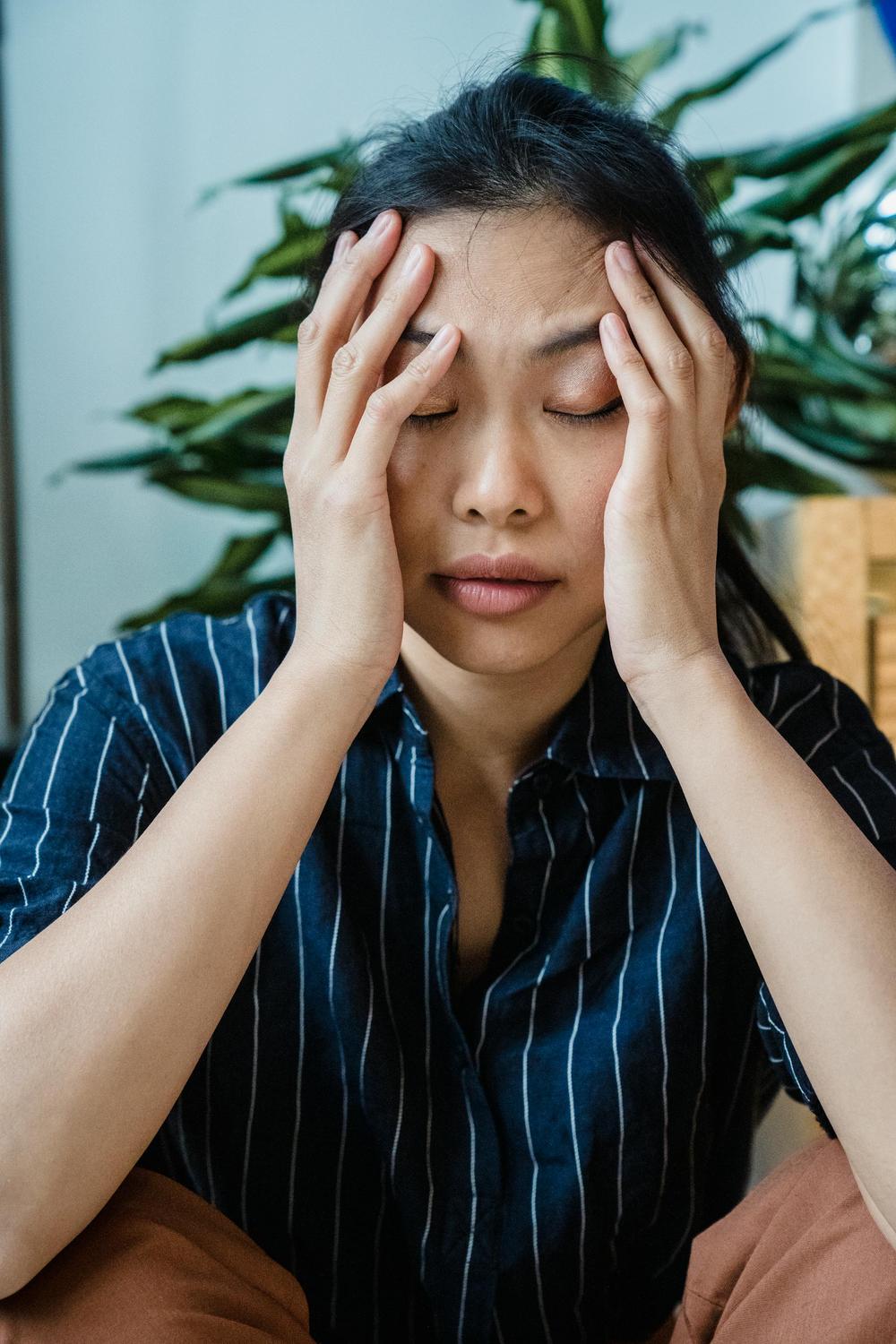

The hallmark of sleep paralysis is the complete inability to move, despite being fully conscious. Many individuals also experience hallucinations during episodes – with intruder hallucinations (sensing a threatening presence), incubus hallucinations (a sensation of pressure on the chest), and vestibular-motor hallucinations (out-of-body experiences) being commonly reported. The emotional response is dominated by intense fear and panic, further compounding the distress of these episodes. Episodes can occur as individuals fall asleep (hypnagogic) or upon awakening (hypnopompic), with the latter being more common.

What Triggers Sleep Paralysis Episodes?

Modifiable factors play a significant role in triggering sleep paralysis. Sleep deprivation, irregular sleep schedules from shift work or jet lag, and particularly the supine (back) sleeping position can increase the likelihood of episodes. In addition, sleep disorders such as obstructive sleep apnea and narcolepsy, along with psychological factors including stress, anxiety, and PTSD, contribute to episode frequency. Lifestyle influences like caffeine and alcohol consumption, substance use, and even physical exhaustion further exacerbate vulnerability.

How Is Sleep Paralysis Diagnosed and Assessed?

Diagnosis primarily relies on clinical interviews and detailed symptom descriptions rather than laboratory tests. Healthcare professionals assess key features such as the temporary inability to move or speak and the presence of hallucinations. Sleep diaries and validated questionnaires like the Sleep Paralysis Experiences and Phenomenology Questionnaire (SP-EPQ) or the Waterloo Unusual Sleep Experience Questionnaire (WUSEQ) assist in diagnostics. Polysomnography (PSG) and the Multiple Sleep Latency Test (MSLT) can be used, especially when differentiating sleep paralysis from narcolepsy.

What Evidence-Based Approaches Exist for Managing Sleep Paralysis?

Management is centred on behavioural interventions, primarily through sleep hygiene optimisation. Establishing a consistent sleep schedule, reducing caffeine and alcohol intake, and avoiding screens before bedtime are key measures. Positional therapy, such as avoiding the supine position, has also been shown to help. Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and meditation can alleviate associated anxiety, while treatment of underlying sleep disorders (e.g., using CPAP for obstructive sleep apnea) can reduce episode frequency. Although no immediate cure exists during an episode, small intentional movements and steady breathing may help accelerate recovery.

Understanding the Cultural and Historical Context of Sleep Paralysis

Sleep paralysis has been interpreted through various cultural lenses. In Newfoundland, it is known as the “Old Hag” phenomenon; in Japan, as “kanashibari”; and in Hong Kong, as “ghost oppression.” These diverse interpretations highlight how cultural beliefs shape the experience of sleep paralysis. Historical accounts date back to the 10th century, and literary references by authors like Guy de Maupassant and Fyodor Dostoyevsky further underscore its longstanding presence in human consciousness.

The Prognosis and Long-Term Outlook for Sleep Paralysis

From a physiological standpoint, sleep paralysis is benign with no long-term health consequences. Episodes may fluctuate over time, with many individuals experiencing only isolated incidents or a reduction in frequency as triggers are managed. The primary challenge is often psychological, with episode-related anxiety potentially creating a vicious cycle of sleep deprivation. However, education about the benign nature of the condition and proper sleep management significantly improves quality of life.

Moving Forward With Understanding and Evidence

Sleep paralysis, while distressing during episodes, is ultimately a temporary dissociation between consciousness and the natural muscle paralysis of REM sleep. A comprehensive understanding of its neurobiological and cultural dimensions has paved the way for effective management strategies. With evidence-based interventions and proper guidance from healthcare professionals, individuals can confidently manage their sleep health and reduce the frequency and impact of sleep paralysis episodes.

Is sleep paralysis dangerous or a sign of a serious medical condition?

Sleep paralysis itself is not dangerous and does not indicate a serious medical condition in the vast majority of cases. Although the episodes can be extremely distressing, they are benign and typically resolve on their own within minutes. However, if episodes become frequent or are accompanied by other concerning symptoms, it is advisable to consult a healthcare professional.

Why do I only experience sleep paralysis when sleeping on my back?

The supine (back) sleeping position has been shown to significantly increase the likelihood of sleep paralysis episodes. This may be due to airway dynamics and changes in breathing patterns that occur when sleeping on your back. Many individuals find that switching to a side or stomach sleeping position can help reduce the frequency of episodes.

Can stress and anxiety cause sleep paralysis?

Yes, stress and anxiety are significant risk factors for sleep paralysis. They can disrupt normal sleep patterns and fragment REM sleep, ultimately increasing vulnerability to episodes. Managing stress through techniques like meditation, deep breathing, and cognitive behavioural therapy can help reduce the frequency of sleep paralysis.

How can I stop a sleep paralysis episode once it starts?

There is no immediate intervention that can instantly end a sleep paralysis episode, as the condition is rooted in neurobiological processes. However, many individuals find that focusing on small intentional movements—such as wiggling fingers or toes—and maintaining steady, deep breathing can help alleviate the distress of the episode and may encourage it to resolve more quickly.

Should I see a doctor about sleep paralysis?

For occasional sleep paralysis episodes, medical consultation is usually not necessary. However, if the episodes occur frequently, cause significant distress, or are accompanied by other symptoms such as excessive daytime sleepiness, it is advisable to seek medical advice. This is particularly important if there is a suspicion of an underlying sleep disorder such as narcolepsy or sleep apnea.