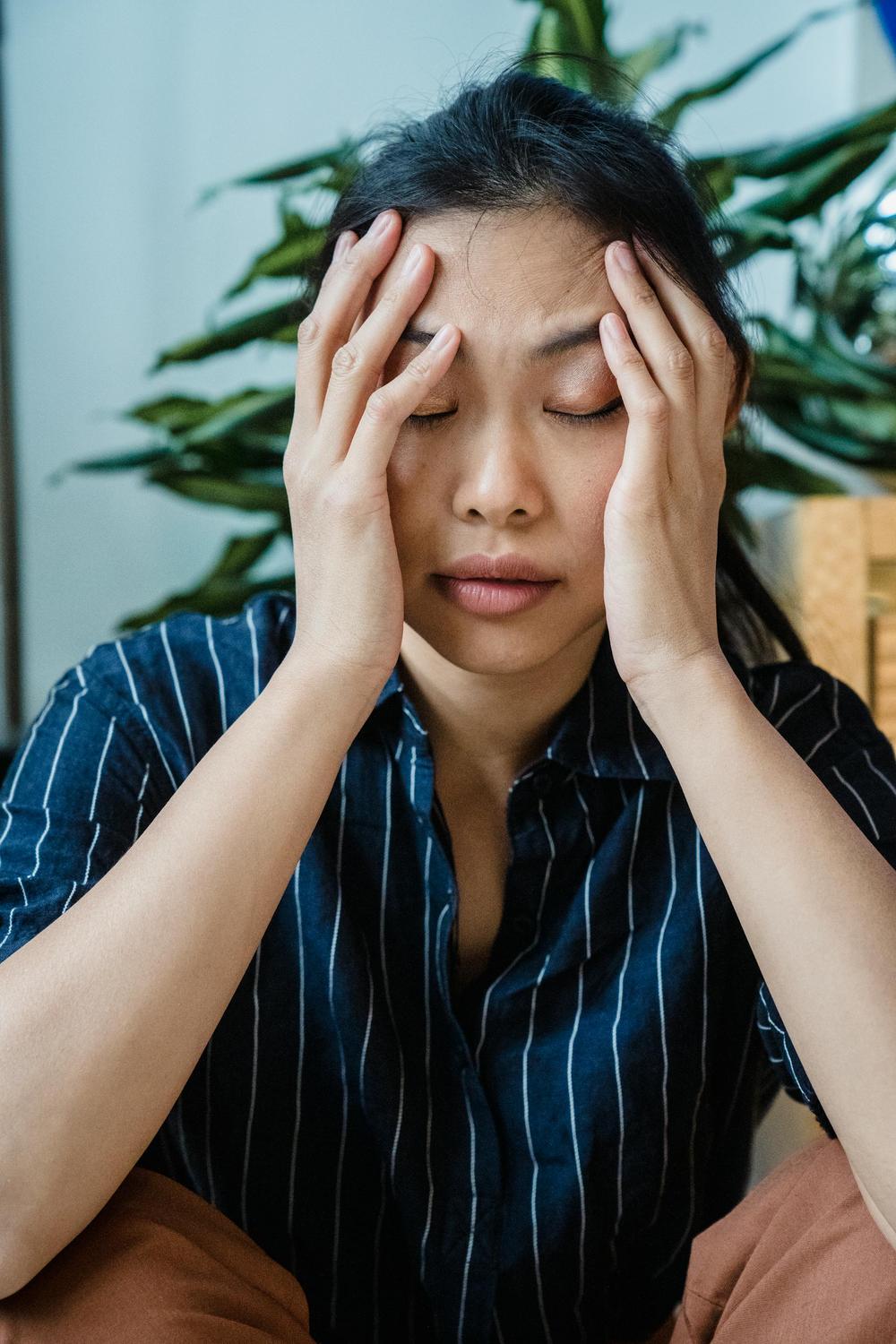

In an era where professionals face an unprecedented deluge of information, tasks, and competing demands, the human mind has become an overwhelmed repository of uncompleted commitments. Research demonstrates that unfinished tasks continually draw cognitive attention, creating persistent psychological pressure that diminishes both productivity and wellbeing. The average knowledge worker juggles dozens of projects simultaneously whilst managing hundreds of daily inputs across multiple channels—email, meetings, phone calls, and spontaneous ideas—all vying for mental bandwidth. This cognitive overload doesn’t merely reduce efficiency; it fundamentally compromises our ability to think strategically, make sound decisions, and maintain the mental clarity essential for professional excellence. David Allen’s Getting Things Done (GTD) methodology, first published in 2001 and refined over two decades, offers a scientifically grounded solution: the systematic collection and processing of all mental commitments through a structured inbox system that transforms chaos into actionable clarity.

What Is the Getting Things Done Inbox and Why Does It Matter?

The Getting Things Done inbox represents far more than a simple collection point for tasks. It functions as the critical first stage in Allen’s five-step workflow, serving as a catch-all repository for anything that captures your attention. Unlike traditional to-do lists that blend collection, decision-making, and action, the GTD inbox operates as a dedicated processing station—a triage point where “stuff” enters the system before undergoing systematic clarification and organisation.

Allen’s methodology rests on a foundational principle articulated elegantly in his original work: “there is an inverse relationship between things on your mind and those things getting done.” This observation, now supported by extensive cognitive science research, reveals why professionals who attempt to manage commitments mentally experience heightened stress and reduced effectiveness. The inbox addresses this through immediate, comprehensive capture of all inputs into a trusted external system.

The power of this approach becomes evident when examining what qualifies for inbox inclusion. Every task, idea, commitment, email, meeting note, article reference, creative thought, and problem requiring attention enters the inbox. This comprehensive capture creates a single, unambiguous destination for all inputs, eliminating the mental friction of deciding where information should reside. More critically, it prevents the accumulation of mental clutter that research demonstrates reduces creativity and impairs decision-making capacity.

Time Magazine called Getting Things Done “the self-help business book of its time” in 2007, and over two million people globally have been introduced to its methodology. This widespread adoption reflects not mere popularity, but practical effectiveness validated through both professional experience and scientific research. The 2008 study published in Long Range Planning by Francis Heylighen and Clément Vidal found that “recent insights in psychology and cognitive science support and extend GTD’s recommendations,” providing empirical backing for Allen’s intuitive framework.

How Does the Collection Method Address Cognitive Load?

The scientific foundation of Allen’s collection method centres on two well-established psychological phenomena: The Zeigarnik Effect and cognitive load theory. The Zeigarnik Effect, named after Soviet psychologist Bluma Zeigarnik, demonstrates that human brains are hardwired to remember unfinished tasks. These “open loops” or “incompletes” persistently demand mental attention, creating psychological pressure that persists until either the task completes or a concrete plan exists for its completion.

Once a clear plan emerges—even if execution hasn’t begun—these persistent mental signals diminish significantly. This neurological reality explains why creating comprehensive lists feels immediately relieving; the act of externalising commitments satisfies the brain’s requirement for closure, freeing working memory for productive thought.

Cognitive load research reinforces this approach from a different angle. When working memory processes excessive information simultaneously, both creativity and decision-making quality deteriorate measurably. Neuroscientist Daniel Levitin argues in “The Organized Mind: Thinking Straight in the Age of Information Overload” that external systems become essential for managing and prioritising the information deluge characterising modern professional life. These systems don’t merely assist forgetful memories; they fundamentally free minds to wander creatively rather than constantly cycling through mental checklists.

Allen’s collection method leverages these cognitive realities through deliberate system design. By establishing clear, readily accessible inboxes—whether physical trays, digital applications, or notebooks—the methodology ensures that capture happens immediately when items enter awareness. This immediacy proves crucial; delayed capture allows items to re-enter mental circulation, defeating the system’s core purpose.

The method’s effectiveness relies on maintaining what Allen terms a “mind like water,” borrowing from martial arts philosophy. Water responds proportionally to objects entering it—a small stone creates a small splash, a boulder creates a large one—then returns immediately to calm equilibrium. Similarly, the properly functioning GTD system allows minds to respond appropriately to actual demands without remaining perpetually agitated by accumulated mental clutter.

What Are the Essential Characteristics of an Effective GTD Inbox?

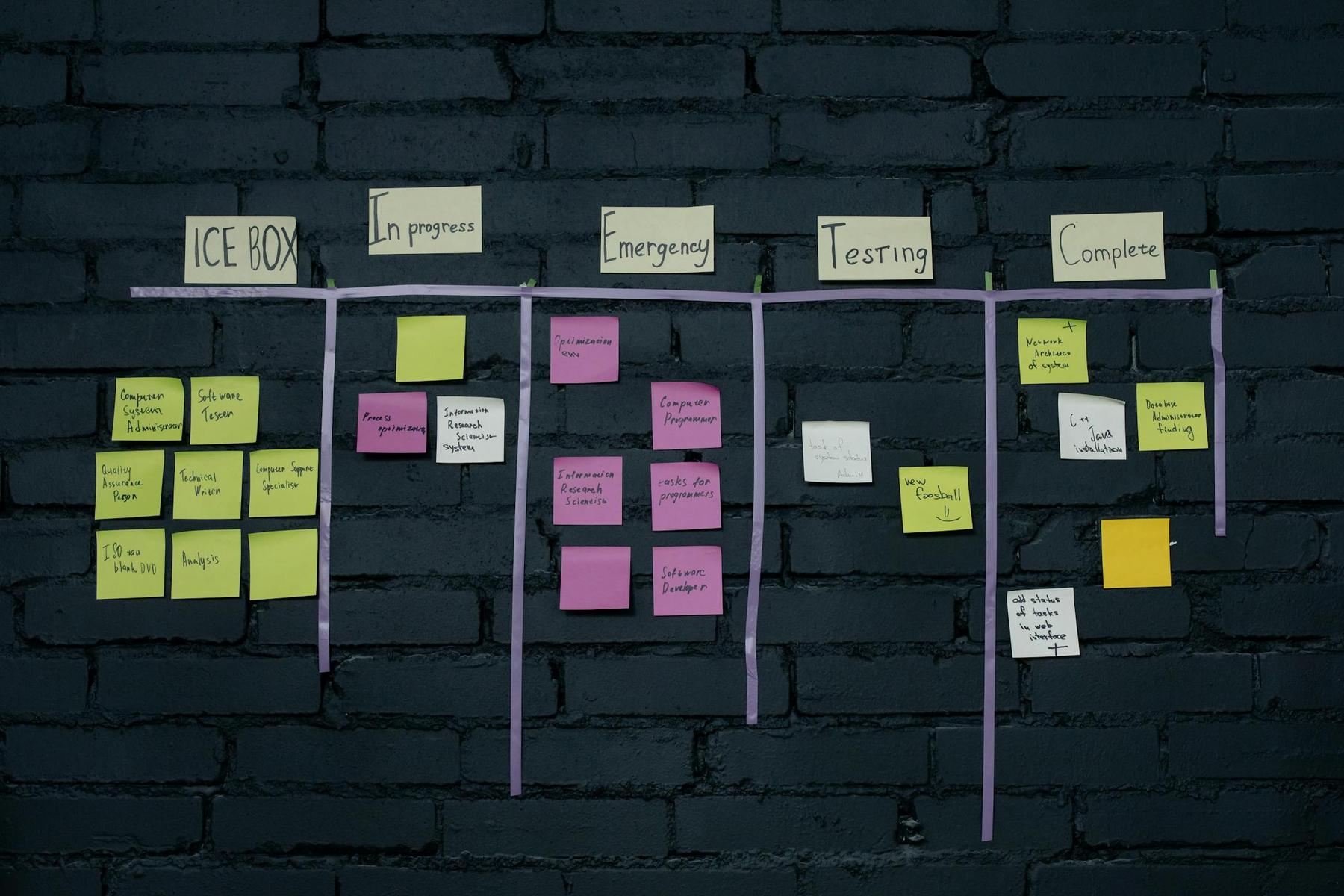

Creating an effective inbox requires understanding specific design principles that distinguish functional collection systems from ineffective accumulation points. Allen emphasises that practitioners should maintain “as many in-trays as you need and as few as you can get by with.” This seemingly paradoxical guidance reflects the tension between accessibility and complexity; multiple inboxes increase capture convenience but multiply processing demands.

The paramount characteristic of any effective inbox involves ready accessibility. Collection tools must remain within easy reach during moments when capture becomes necessary. A notebook carried consistently proves more valuable than sophisticated software accessed irregularly. This accessibility principle explains why many successful GTD practitioners maintain multiple strategic inboxes: a physical tray for paper documents, email for digital communications, and a mobile application for ideas arising outside the office.

Regular emptying constitutes the second non-negotiable characteristic. Allen insists that inboxes should be processed and emptied at minimum weekly, ideally daily. “Empty” in this context doesn’t require completing all work; rather, it means making decisions about each item’s status and proper location. Chronic unprocessed inboxes create the very mental stress the system aims to eliminate, as uncertainty about inbox contents generates persistent low-level anxiety.

Research on email management—where inbox overload proves most pernicious—demonstrates that “it takes much less energy to maintain e-mail backlog at zero than at a thousand.” This counterintuitive reality reflects the psychological weight of accumulated undecided items. Each unprocessed email represents an unmade decision, contributing to cognitive load regardless of whether the email itself requires significant action.

Visual clarity provides the third essential characteristic. Effective inboxes make their status immediately apparent; practitioners should recognise at a glance whether items await processing. This transparency prevents the dangerous pattern of inbox numbness, where accumulated items become invisible through familiarity. The physical satisfaction of emptying a tangible in-tray or achieving “inbox zero” in email provides concrete feedback that reinforces consistent system use.

Allen’s methodology remains deliberately technologically neutral, acknowledging that both paper-based and digital systems function effectively when properly implemented. The critical factor involves process adherence rather than tool selection. Sophisticated applications cannot compensate for irregular processing, whilst simple paper systems excel when used consistently.

| Inbox Characteristic | Purpose | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Ready Accessibility | Enables immediate capture without friction | Physical tray on desk; mobile app with widget access; notebook in pocket |

| Regular Emptying | Prevents accumulation and maintains system trust | Daily email processing; weekly physical inbox review; scheduled processing time |

| Visual Clarity | Makes inbox status immediately apparent | Clear desktop tray; inbox count visible; dedicated notebook section |

| Minimal Number | Reduces processing burden whilst maintaining coverage | Work email, personal capture app, home physical tray (typically 2-4 total) |

| No Long-term Storage | Maintains inbox as processing station, not archive | Items move to projects, reference, or actions after clarification |

How Does the Five-Step Workflow Transform Inbox Contents Into Actionable Systems?

The collection method gains power through integration within Allen’s complete five-step workflow: Capture, Clarify, Organise, Reflect, and Engage. Understanding this workflow reveals how the inbox functions as the critical entry point for a comprehensive productivity architecture.

Capture represents the initial stage where anything commanding attention enters collection tools. The objective involves externalising all commitments, ideas, and inputs without filtering or organising. Successful capture requires noting sufficient detail to understand the item’s meaning later, whilst avoiding premature analysis that slows collection. The Two-Minute Rule doesn’t apply during capture; even quick tasks simply enter the inbox for subsequent processing.

Clarify transforms raw inbox contents into actionable information through systematic decision-making. Processing each item requires asking fundamental questions: What is this? Is it actionable? What does completion look like? What specific next physical action would move this forward? During this stage, the Two-Minute Rule activates—tasks requiring less than two minutes receive immediate execution. This threshold balances processing efficiency against task completion, as scheduling brief tasks consumes more time than simply completing them.

Non-actionable items branch into three categories: trash (irrelevant or outdated), reference material (information without action requirements), or someday/maybe possibilities (interesting but not current priorities). Actionable items undergo further analysis to determine their scope. Single-step tasks become next actions; multi-step initiatives become projects requiring next-action definition.

Organise places clarified items into appropriate systems reflecting their nature and timing. Calendar events receive time-specific scheduling. Next actions populate context-organised lists—phone calls, computer tasks, errands, or location-specific activities. Projects establish in a master list tracking all multi-step outcomes. Waiting-for items create a tickler system for delegated responsibilities. Reference materials file systematically for future retrieval.

Reflect provides the crucial perspective-building stage through two review types. Daily reviews involve quick checks of calendars and next-action lists each morning and evening, maintaining awareness of immediate commitments. Weekly reviews—the “backbone of GTD system” according to Allen—dedicate one to two hours for comprehensive system assessment. This non-negotiable component prevents system decay by ensuring nothing falls through organisational cracks whilst maintaining perspective on overall progress.

Engage represents actual task execution, guided by decision criteria determining which action merits attention. Context considerations ask whether the current situation and location support specific tasks. Priority assessment evaluates which available activities generate greatest impact. Energy levels indicate whether sufficient mental or physical capacity exists for demanding work. Time availability determines whether adequate duration exists for meaningful progress. Together, these criteria enable decisive action selection without perpetual re-evaluation.

Allen’s Six-Level Model—Horizons of Focus—provides additional perspective ranging from daily actions (Ground level) through current projects (Horizon 1), areas of responsibility (Horizon 2), one-to-two-year goals (Horizon 3), long-term vision (Horizon 4), to life purpose and principles (Horizon 5). This framework ensures tactical daily choices align with strategic direction.

What Challenges Commonly Arise When Implementing the Collection Method?

Despite its conceptual elegance, implementing Allen’s collection method presents predictable challenges that derail many practitioners. Understanding these obstacles and their solutions proves essential for sustained system effectiveness.

Inbox overload represents the most common initial challenge. Professionals beginning GTD often face accumulated backlogs—thousands of emails, piles of papers, and years of mental commitments—creating overwhelming processing demands. Allen acknowledges this reality, noting that initial processing sessions may consume one to six hours depending on backlog severity. The solution involves commitment to systematic processing rather than emergency scanning. Processing items sequentially from top to bottom, regardless of apparent urgency or interest, ensures comprehensive inbox clearance whilst preventing cherry-picking that leaves difficult decisions perpetually unaddressed.

Email presents unique challenges due to volume exceeding traditional physical inboxes. David Allen noted clients with over 7,000 emails in their inbox—each representing an unmade decision contributing to cognitive burden. Email management requires disciplined application of GTD principles: ruthless deletion, immediate Two-Minute Rule responses, strategic filing separating action items from reference material, and systematic top-to-bottom processing. Creating folders for @ACTION (items requiring more than two minutes) and @WAITING FOR (responses needed from others) transforms email from swamp to organised system.

Over-complication undermines many implementation attempts as enthusiastic practitioners layer sophisticated tools and elaborate categorisation schemes atop foundational practices they haven’t yet mastered. Allen’s recommendation proves refreshingly pragmatic: start with paper-based systems using pens, paper, and filing trays. Master fundamental capture, clarification, and organisation before introducing digital complexity. The methodology’s technological neutrality reflects recognition that process mastery matters more than tool sophistication.

Inconsistent system usage represents perhaps the most pernicious challenge, as GTD requires sustained commitment for effectiveness. The weekly review—Allen’s “non-negotiable component”—frequently falls victim to competing demands despite being the system’s critical success factor. Solutions involve treating weekly review as protected time, ideally scheduled during periods of natural reflection such as Sunday afternoons. Many practitioners find that the stress of neglected weekly reviews motivates consistent practice more effectively than willpower alone.

Multiple capture tools create coordination challenges, particularly when professional and personal contexts require separate systems—work email, personal mobile applications, home physical trays. The solution involves minimising inbox number whilst acknowledging that some separation proves necessary. Critical requirements include reviewing all inboxes during weekly review and establishing clear criteria determining which items enter which inbox.

Why Does the Collection Method Prove Particularly Valuable for Healthcare Professionals?

Healthcare professionals face distinctive challenges that make systematic organisation particularly valuable yet simultaneously difficult to maintain. The intersection of emotional intensity, unpredictable schedules, physical demands, and complex documentation requirements creates an environment where mental clarity becomes both essential and elusive.

Research from the National Academy of Medicine indicates that between 35-45% of physicians and nurses report burnout symptoms, with rates climbing to 40-60% among medical students and residents. This burnout directly impacts not merely professional satisfaction but patient care quality, with measurable increases in errors and complications correlating with healthcare worker stress levels.

A comprehensive study examining 11,700 employees demonstrated that overall wellbeing significantly predicts healthcare costs, productivity, and retention outcomes. Baseline wellbeing predicted follow-up healthcare utilisation, absenteeism, presenteeism, and job performance. Critically, changes in wellbeing linked to changes in all employer outcomes, suggesting that interventions improving wellbeing generate measurable organisational benefits.

The Getting Things Done collection method addresses several burnout contributors through structured external systems that reduce cognitive load. Healthcare professionals juggle patient care responsibilities, documentation requirements, continuing education commitments, administrative tasks, and personal obligations—creating precisely the mental overload that GTD mitigates through comprehensive capture and systematic processing.

Time management research in healthcare settings demonstrates that structured frameworks reduce stress and improve patient outcomes by freeing professionals to focus on direct care rather than administrative navigation. Strategies including prioritisation, delegation, and systematic organisation align closely with GTD principles, suggesting methodological synergy between productivity systems and healthcare performance.

Workplace interventions for mental health show significant improvements in wellbeing, work engagement, and resilience when organisational support combines with individual skill development. The Getting Things Done methodology provides precisely this type of individual capability—a portable skill set applicable across career transitions and organisational changes.

The CDC identifies several protective factors against healthcare burnout: trust in management, ability to participate in decisions, and safe work environments. Whilst GTD cannot create these organisational conditions directly, it provides individual practitioners with enhanced control and clarity that research demonstrates reduces stress. The sense of control emerging from comprehensive system implementation may buffer against organisational stressors whilst improving capacity to engage constructively in workplace decisions.

Professional coaching interventions in healthcare settings demonstrate improvements in emotional exhaustion scores, resilience, and quality of life. The structured reflection inherent in GTD’s weekly review provides similar benefits through systematic assessment of commitments, progress, and priorities. This regular reflection opportunity allows healthcare professionals to identify overcommitment patterns, recognise accomplishments that daily urgency obscures, and maintain perspective on long-term professional development amidst immediate care demands.

Transforming Professional Chaos Into Systematic Clarity

The Getting Things Done inbox collection method represents more than organisational technique; it embodies a fundamental shift in how professionals relate to information and commitments. By establishing external systems that comprehensively capture all inputs, systematically clarify their meaning and requirements, and organise them into actionable structures, practitioners achieve what Allen terms “mind like water”—the capacity to respond appropriately to actual demands rather than being perpetually overwhelmed by accumulated mental clutter.

Research spanning cognitive science, organisational psychology, and workplace wellbeing validates the methodology’s core insights. The Zeigarnik Effect explains why unprocessed commitments generate persistent mental stress. Cognitive load research demonstrates that external systems free working memory for creative and strategic thinking. Workplace wellbeing studies confirm that control and clarity reduce burnout whilst improving both satisfaction and performance.

Implementation demands commitment—Allen notes that fully mastering GTD requires approximately two years—yet the benefits emerge progressively throughout the learning journey. Initial processing sessions clear accumulated backlogs, creating immediate relief. Weekly reviews maintain system integrity whilst building comprehensive awareness of commitments and progress. Daily capture prevents new mental accumulation, establishing sustainable practices that compound over professional lifetimes.

The methodology’s technological neutrality ensures longevity beyond specific tools or trends. Whether implemented through paper notebooks, sophisticated applications, or hybrid systems, the fundamental workflow remains constant: capture everything, clarify meaning, organise systematically, reflect regularly, engage decisively. These principles transcend technological change, organisational restructuring, and career transitions, providing portable capabilities applicable across professional contexts.

For healthcare professionals navigating particularly demanding environments characterised by high stakes, emotional intensity, and complex coordination requirements, the collection method offers valuable support. By reducing cognitive burden through comprehensive external systems, practitioners protect the mental clarity essential for patient care whilst managing the administrative and professional development commitments inherent in healthcare careers. The resulting stress reduction, improved control, and enhanced perspective contribute to both individual wellbeing and organisational effectiveness.

As professionals face accelerating information flows, expanding responsibilities, and increasing complexity, systematic approaches to managing commitments transition from optional optimisation to essential capability. The Getting Things Done inbox collection method provides a scientifically grounded, practically validated framework for transforming overwhelming chaos into actionable clarity—enabling not merely enhanced productivity but the mental spaciousness required for creativity, strategic thinking, and sustained professional excellence.

How many inboxes should I maintain in the Getting Things Done system?

David Allen advises maintaining “as many in-trays as you need and as few as you can get by with,” reflecting the balance between capture accessibility and processing burden. Most practitioners effectively operate with two to four inboxes: typically work email, a physical tray for paper documents, a mobile capture application for ideas arising outside the office, and possibly a home inbox for personal matters. The critical requirement involves reviewing all inboxes during your weekly review to prevent items scattering across unchecked systems. Start minimally—a single physical tray and email inbox—then add collection points only when clear capture gaps emerge that reduce system effectiveness.

What distinguishes the GTD inbox from a traditional to-do list?

The Getting Things Done inbox functions as a processing station rather than an action list. Traditional to-do lists blend capture, organisation, and prioritisation, creating confusion about status and next steps. The GTD inbox serves exclusively as a collection point for raw, unprocessed inputs requiring clarification. Items don’t remain in the inbox indefinitely; instead, they undergo systematic processing during which you determine actionability, define next actions, and move them to appropriate organised lists. This separation between collection and organisation prevents the inbox numbness that occurs when undifferentiated items accumulate without clear handling protocols.

How does the Two-Minute Rule apply to inbox processing?

The Two-Minute Rule activates during the Clarify stage of inbox processing, not during initial capture. When processing inbox items, if a task requires less than two minutes to complete, execute it immediately rather than adding it to action lists. This threshold reflects practical efficiency: scheduling brief tasks consumes more time than simply completing them. However, this rule applies only during dedicated processing time, not whenever quick tasks arise throughout the day, helping to prevent constant interruptions.

Why does David Allen consider the weekly review “non-negotiable” for GTD effectiveness?

The weekly review serves as the backbone of the GTD system because it maintains system integrity, perspective, and trust. Without regular comprehensive review, items slip through organisational gaps, system components drift out of synchronisation, and practitioners lose confidence that their external systems reliably capture all commitments. Typically requiring one to two hours, the weekly review involves processing all inboxes, updating project lists, reviewing next actions, and ensuring calendar accuracy, thereby preventing gradual system decay and reinforcing mental clarity.

Can the Getting Things Done system work effectively with paper-based tools, or does it require digital applications?

David Allen’s methodology is deliberately technologically neutral, functioning equally well with paper-based systems and digital applications. In fact, Allen often recommends that beginners start with paper-based tools—like notebooks and filing trays—to master the fundamental processes of capture, clarification, and organisation before introducing digital complexity. Many experienced practitioners use a hybrid approach, leveraging the tangibility of paper for certain tasks while using digital tools for their advantages in searchability and synchronisation.