The sensation is familiar to millions: persistent fatigue that sleep doesn’t cure, mental fog that coffee can’t clear, and a body that feels simultaneously wired and exhausted. Whilst we often attribute these experiences to the psychological burden of modern life, emerging scientific evidence reveals a profound biological truth—chronic stress fundamentally disrupts the cellular power stations that sustain every aspect of human vitality. Understanding the intricate relationship between stress and mitochondrial function represents one of the most significant advances in our comprehension of how psychological experiences translate into tangible physiological consequences.

The connection between stress and cellular energy is neither abstract nor trivial. Mitochondria, the microscopic organelles responsible for producing approximately 90% of the energy currency that powers cellular reactions, stand at a critical juncture where psychosocial factors meet biological response systems. When these cellular powerhouses falter under the weight of persistent stress, the ramifications extend far beyond simple tiredness—they cascade through metabolic, neurological, and immune systems, fundamentally altering how our bodies function at the most elementary level.

What Are Mitochondria and Why Do They Matter for Cellular Energy?

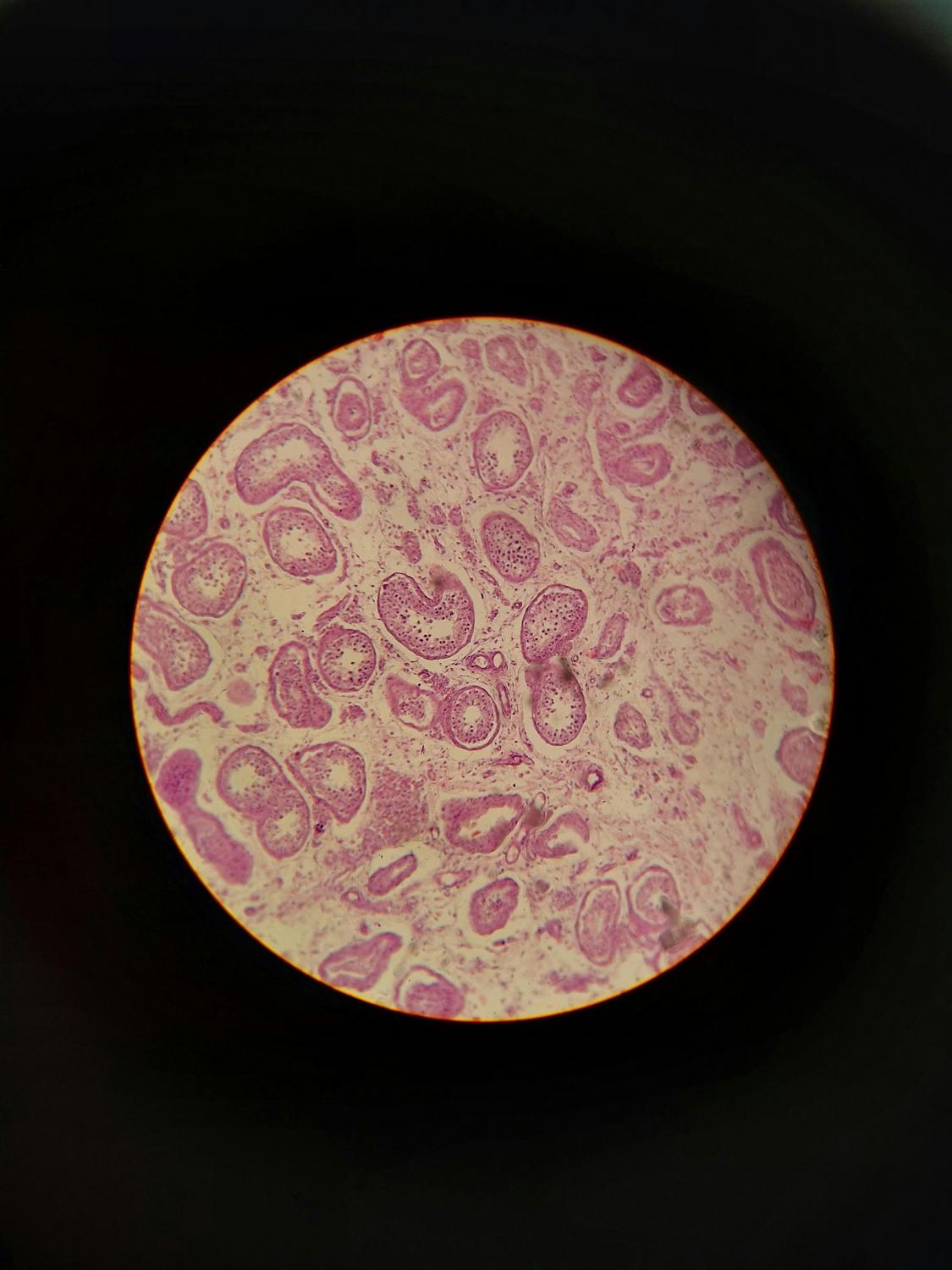

Mitochondria represent the only subcellular organelles to contain their own genetic material—distinct from the DNA housed in the cell nucleus. Each human cell harbours between 100 and 1,000 of these energy-transforming structures, with the precise number depending on the energy demands of specific tissue types. Brain cells, cardiac muscle, and hepatocytes contain particularly abundant mitochondrial populations, reflecting their extraordinary metabolic requirements.

These remarkable organelles transform food substrates—glucose, lipids, and amino acids—alongside oxygen into adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the universal energy currency that powers cellular reactions. This process, termed oxidative phosphorylation, occurs through the electron transport chain located within the inner mitochondrial membrane. The efficiency of this system determines cellular vitality; when mitochondrial function falters, energy production plummets.

The magnitude of mitochondrial importance becomes evident when considering that ATP powers approximately 90% of all cellular reactions. From neurotransmitter synthesis to immune cell activation, from protein construction to ion pump operation, virtually every biological process depends upon adequate ATP availability. The brain, despite representing merely 2% of body mass, consumes roughly 20% of the body’s total energy—rendering it particularly vulnerable to defects in mitochondrial energy production.

Beyond energy generation, mitochondria function as sophisticated signalling centres. They synthesise steroid hormones within their matrix, regulate calcium homeostasis, produce mitochondria-derived peptides called mitokines that influence systemic metabolism, and coordinate cellular responses to oxidative stress. This positions mitochondria not merely as passive energy generators, but as active participants in cellular decision-making and whole-organism homeostasis.

How Does Stress Increase Your Cellular Energy Demands?

The physiological stress response—whether triggered by genuine threats or imagined concerns—represents one of the most energy-intensive biological processes. Every component of this response system demands substantial ATP expenditure, creating acute and sustained increases in cellular energy requirements.

When the brain perceives a stressor, it activates two primary systems: the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and the sympathetic-adrenal-medullary (SAM) axis. Each aspect of these stress responses is fundamentally energy-dependent. Gene expression and protein synthesis during stress require four ATP molecules per amino acid incorporated into proteins. Neurotransmitter release and subsequent reuptake necessitate constant ATP hydrolysis. The cardiovascular system alone experiences dramatic increases in energy demand, with psychological stress elevating heart rate and blood pressure by 10-20%, directly augmenting cardiac ATP requirements.

The brain’s energy consumption intensifies during stress exposure, with increased cerebral glucose oxidation and oxygen consumption documented across multiple brain regions. Research indicates that stress-induced escalation in cerebral energy demand may require adrenergic signalling by catecholamines—stress hormones that themselves require mitochondrial ATP for synthesis and release.

| Mitochondrial Parameter | Acute Stress Effects | Chronic Stress Effects |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Production (ATP) | May temporarily enhance within hours | Decreased synthesis capacity; reduced efficiency |

| Reactive Oxygen Species | Initial adaptive antioxidant upregulation | Excessive ROS production; oxidative damage |

| Mitochondrial Morphology | Possible enlargement; minor ultrastructure changes | Fragmentation, swelling, abnormal cristae structure |

| mtDNA Integrity | Minimal acute damage | Accumulated mutations and deletions |

| Membrane Potential | Generally maintained | Depolarisation; reduced gradient |

| Biogenesis | Not substantially affected | Impaired formation of new mitochondria |

| Mitophagy | Normal quality control | Dysregulated removal of damaged organelles |

This energy crisis extends beyond immediate metabolic demands. The synthesis of stress hormones themselves occurs within mitochondria. All steroid hormones, including cortisol, are produced through enzymatic processes within the mitochondrial matrix. The rate-limiting step involves importing cholesterol into mitochondria via the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein. Research examining mice with specific mitochondrial protein mutations revealed that stress-induced corticosterone release was blunted by over 50%, demonstrating the bidirectional relationship between mitochondrial function and stress hormone production.

What Happens to Mitochondria Under Chronic Stress Exposure?

Whilst acute stress may trigger adaptive mitochondrial responses within hours, chronic stress exposure fundamentally recalibrates mitochondrial structure and function—a phenomenon termed “mitochondrial allostatic load” (MAL). A systematic review of 23 experimentally-controlled animal studies revealed that 82% reported stress-induced impairments in mitochondrial function, with only four studies documenting temporary increases in mitochondrial activity.

The concept of MAL describes the cumulative structural and functional changes mitochondria undergo when subjected to persistent stressors. This framework illuminates how psychological experiences translate into cellular-level consequences that precede and amplify traditional stress biomarkers. The relationship between stress duration and mitochondrial changes follows an inverted U-shaped pattern—initial adaptive responses become progressively maladaptive as stress extends, reflecting diminishing system resilience and exhausted adaptive capacity.

Chronic stress dismantles mitochondrial integrity through multiple concurrent mechanisms. Mitochondrial DNA, which lacks the protective structures of nuclear DNA, accumulates mutations and deletions. These genetic alterations reduce the efficiency of ATP production, with complex IV (cytochrome c oxidase) most frequently affected across studies. The morphology of mitochondria transforms dramatically—normally elongated, interconnected networks fragment into isolated, globular structures with abnormal internal architecture.

The production of reactive oxygen species (ROS)—inherently generated during normal energy metabolism—escalates under chronic stress conditions. Approximately 1-2% of oxygen consumed by mitochondria typically diverts to ROS formation. However, chronic stress disrupts this delicate balance, overwhelming antioxidant defence systems. Unstable ROS molecules attack lipids, proteins, and mitochondrial DNA, creating a vicious cycle wherein damaged mitochondria produce excessive ROS, which inflicts further damage.

Mitochondrial biogenesis-the process by which cells construct new mitochondria—becomes impaired under sustained stress. This reduces the body’s capacity to replace damaged organelles, whilst simultaneously increasing vulnerability to oxidative damage. Mitophagy, the quality control mechanism responsible for selectively removing dysfunctional mitochondria, also falters. Damaged mitochondria accumulate within cells, amplifying inflammatory signals and perpetuating oxidative stress.

How Do Stress Hormones Directly Affect Mitochondrial Function?

The relationship between stress hormones and mitochondria transcends simple cause-and-effect—it represents a sophisticated bidirectional dialogue that shapes both stress responses and metabolic outcomes. Glucocorticoid receptors, upon binding cortisol, translocate directly into mitochondria where they interact with glucocorticoid response elements on mitochondrial DNA. This direct genetic interaction allows stress hormones to rapidly modulate mitochondrial gene expression and respiratory chain function.

Research demonstrates that cortisol exerts biphasic effects on mitochondrial function. At physiological concentrations, glucocorticoids potentiate mitochondrial calcium sequestration and maintain membrane potential—adaptive responses that support cellular energy demands during stress. However, after 24 hours of supra-physiological exposure, these protective effects dissipate, culminating in mitochondrial dysfunction and collapsed membrane potential.

Stress hormones orchestrate widespread metabolic changes with direct mitochondrial consequences. Glucocorticoids elevate circulating glucose and lipid concentrations within minutes through increased hepatic gluconeogenesis, decreased skeletal muscle glucose uptake, and antagonism of insulin signalling in adipose tissue. This stress-induced hyperglycaemia creates a pre-diabetic metabolic state that independently damages mitochondria and promotes mtDNA deletions.

The sympathetic nervous system’s catecholamines—epinephrine and norepinephrine—are metabolised by monoamine oxidases anchored to the outer mitochondrial membrane. Individuals with specific mitochondrial genetic defects affecting ATP transport exhibit elevated resting catecholamine levels, demonstrating that mitochondrial health influences stress hormone dynamics. This bidirectional interaction positions mitochondria as both responders to and modulators of neuroendocrine stress signalling.

Chronic stress gradually induces glucocorticoid resistance, wherein tissues become progressively insensitive to the anti-inflammatory effects of cortisol. Simultaneously, pro-inflammatory cytokines—interleukin-1β, interleukin-6, and tumour necrosis factor-alpha—accumulate, creating a sustained inflammatory milieu that further impairs mitochondrial function. Damaged mitochondria release their contents, including mitochondrial DNA, into circulation where they function as damage-associated molecular patterns, activating innate immune receptors and amplifying inflammation in a self-perpetuating cycle.

Can Mitochondrial Dysfunction Be Reversed Through Lifestyle Modifications?

The relationship between stress and mitochondrial function, whilst profound, demonstrates remarkable plasticity—suggesting that appropriate interventions may restore cellular energy capacity even after significant dysfunction has developed. Research across multiple domains indicates that specific lifestyle modifications exert direct beneficial effects on mitochondrial health, potentially reversing stress-induced impairments.

Exercise represents perhaps the most potent intervention for mitochondrial rejuvenation. Physical activity stimulates mitochondrial biogenesis through activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha (PGC-1α), the master regulator of mitochondrial formation. Exercise training increases mitochondrial content and function in both peripheral tissues and the brain, with moderate activities such as walking demonstrating efficacy. Critically, exercise reverses stress-induced decreases in mitochondrial function and mtDNA copy number, whilst protecting against stress-induced cognitive decline.

The neuroprotective effects of exercise extend beyond simple mitochondrial quantity. Physical activity prevents stress-induced atrophy in the hippocampus—a brain region particularly vulnerable to chronic stress and essential for memory formation. Exercise-induced neurogenesis (formation of new neurons) requires normal mitochondrial dynamics, positioning mitochondrial health as a prerequisite for the cognitive benefits of physical activity. Notably, exercise extends lifespan in aging animal models through mitochondrial rejuvenation, even preventing premature aging phenotypes in genetically predisposed individuals.

Nutritional approaches demonstrate capacity to support mitochondrial function through multiple mechanisms. Ketogenic dietary patterns enhance mitochondrial oxidative metabolism whilst ameliorating insulin resistance. Thoughtful dietary and nutritional support can facilitate mitochondrial substrate utilisation and support various metabolic processes. Antioxidant-rich dietary components reduce anxiety-like behaviours in experimental models, whilst support for the body’s natural antioxidant defences increases stress resilience and extends healthy lifespan.

Sleep hygiene and circadian rhythm maintenance prove essential for mitochondrial health. Sleep provides the critical window for mitochondrial maintenance, mitophagy, and replication. Disrupted circadian patterns—common in shift workers—correlate with impaired mitochondrial function, metabolic dysregulation, and accelerated aging. Establishing consistent sleep-wake cycles supports the natural diurnal variation in stress hormones that optimises mitochondrial efficiency.

Stress management practices including mindfulness meditation, breathwork techniques, and nature exposure demonstrate measurable effects on gene expression patterns, including downregulation of pro-inflammatory pathways. Whilst these interventions require consistent implementation, research indicates they reduce HPA axis activation and may thereby mitigate chronic stress-induced mitochondrial burden. Social support, emotional resources, and a sense of personal control emerge as protective factors against stress-induced mitochondrial dysfunction, suggesting that psychosocial interventions possess tangible cellular benefits.

The Broader Implications of Mitochondrial Stress Biology

The recognition that chronic stress fundamentally disrupts mitochondrial function carries profound implications for understanding how psychological experiences influence physical health trajectories. This cellular-level mechanism illuminates the biological pathways through which adverse experiences “get under the skin,” translating psychosocial adversity into accelerated aging, metabolic dysfunction, cognitive decline, and heightened disease vulnerability.

Research documenting elevated cell-free mitochondrial DNA in individuals with major depression, anxiety disorders, and those who have experienced childhood trauma provides tangible biomarkers of mitochondrial stress. The observation that morning and evening mood states account for 12-15% of variance in subsequent mitochondrial health indices underscores the bidirectional nature of this relationship—psychological states influence mitochondrial function, which in turn shapes neurological and metabolic processes that determine emotional regulation capacity.

The mitochondrial perspective reframes stress-related health outcomes not as inevitable consequences of psychological burden, but as potentially modifiable results of cellular energy dysfunction. This paradigm shift suggests that interventions targeting mitochondrial health—whether through exercise, nutrition, sleep optimisation, or stress management—may prevent or reverse the downstream pathophysiological cascades traditionally associated with chronic stress exposure.

The brain’s particular vulnerability to mitochondrial dysfunction emphasises the neurological consequences of sustained stress. Structural brain changes observed with chronic stress—hippocampal atrophy, prefrontal cortical remodelling, amygdalar expansion—mirror patterns documented in primary mitochondrial disorders. These alterations correlate with measurable cognitive deficits including impaired working memory, reduced learning capacity, and accelerated cognitive decline with aging.

Mitochondrial dysfunction contributes to the metabolic complications of chronic stress, including insulin resistance, dyslipidaemia, and cardiovascular disease. The stress-induced hyperglycaemic state independently damages mitochondria, creating a reinforcing loop wherein metabolic stress exacerbates mitochondrial impairment, which further dysregulates glucose metabolism. Understanding this mechanism provides insight into the elevated diabetes and cardiovascular disease risk documented in individuals with chronic psychological stress or mood disorders.

The inflammatory consequences of mitochondrial stress extend beyond local cellular effects. Circulating mitochondrial components activate systemic inflammatory pathways, with elevated cell-free mitochondrial DNA associated with four-to-eight-fold increased mortality risk in critically ill patients. The gradual development of glucocorticoid resistance under chronic stress creates a pro-inflammatory state that further compromises mitochondrial function, illustrating the multi-system integration of stress biology at the mitochondrial level.

Stress, Mitochondria, and the Future of Cellular Health

The emerging field of mitochondrial stress biology represents a fundamental reconceptualisation of how psychological experiences influence biological aging and disease susceptibility. The mitochondrial allostatic load framework provides a unifying mechanism explaining diverse stress-related pathologies—from metabolic syndrome to neurodegenerative conditions—through the lens of cellular energy dysfunction.

Current research limitations include the paucity of prospective human studies with repeated mitochondrial function measurements and the challenges of assessing mitochondrial function in living humans. Most human investigations rely on blood-derived immune cells, which may not accurately represent mitochondrial status in metabolically active tissues such as brain, heart, or liver. Development of non-invasive mitochondrial assessment methodologies remains a critical research priority.

The reversibility of stress-induced mitochondrial damage emerges as a central question with profound therapeutic implications. Whilst animal research demonstrates that exercise and other interventions can restore mitochondrial function even after significant impairment, translation to human populations requires careful investigation. The existence of sensitive developmental windows during which stress particularly influences mitochondrial programming suggests that early-life interventions may yield disproportionate long-term benefits.

Sex differences in mitochondrial stress responses represent an understudied domain with potential clinical significance. Female and male organisms possess qualitatively different mitochondria with distinct bioenergetic profiles and hormone-responsive characteristics. Most animal stress research has been conducted exclusively in males, whilst human observational studies predominantly include women—creating complementary but incomplete knowledge bases that require integration.

The integration of mitochondrial measures into clinical assessment frameworks could revolutionise how healthcare professionals evaluate stress-related health risks and monitor intervention efficacy. Biomarkers such as circulating cell-free mitochondrial DNA, mitochondrial enzyme activities, and oxidative stress indicators may provide objective metrics complementing subjective symptom reports. However, standardisation of measurement protocols and establishment of clinically meaningful reference ranges remain necessary prerequisites.

Looking to discuss your health options? Speak to us and see if you’re eligible today.

How quickly does chronic stress begin affecting mitochondrial function?

Mitochondrial responses to stress follow a temporal pattern, with initial adaptive changes occurring within hours of acute stress exposure, including temporary increases in antioxidant enzyme expression and minor morphological alterations. However, the maladaptive changes characteristic of mitochondrial allostatic load typically develop over weeks to months of sustained stress exposure. Individual variability in stress resilience, genetic factors, and lifestyle behaviours influence the precise timeline of mitochondrial dysfunction development.

Does mitochondrial dysfunction from stress affect all tissues equally?

Mitochondrial vulnerability to stress-induced dysfunction varies substantially across tissue types, reflecting differential energy demands and antioxidant capacities. The brain demonstrates particular susceptibility due to its extraordinary metabolic requirements and limited regenerative capacity, with regions including the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex showing prominent stress-related mitochondrial changes. Cardiac muscle, with its continuous high-energy demands, similarly exhibits stress-induced mitochondrial impairments. Liver tissue shows rapid mtDNA copy number changes—doubling within four weeks in some stress models—reflecting its central role in metabolic hormone regulation. Skeletal muscle and immune cells also demonstrate measurable mitochondrial alterations, though the magnitude and specific parameters affected differ across tissues.

Can improving mitochondrial health reduce the physical symptoms of chronic stress?

Evidence suggests a bidirectional relationship wherein interventions that enhance mitochondrial function may ameliorate stress-related symptoms. Exercise, which robustly stimulates mitochondrial biogenesis and improves respiratory capacity, demonstrates efficacy in reducing anxiety, improving mood regulation, and enhancing stress resilience. Nutritional approaches supporting mitochondrial metabolism show potential for addressing fatigue, cognitive fog, and metabolic dysregulation associated with chronic stress. Whilst mitochondrial dysfunction represents only one component of the complex stress pathophysiology, addressing cellular energy capacity may interrupt self-perpetuating cycles wherein energy deficits impair stress response systems, further compromising mitochondrial function.

What role does inflammation play in the stress-mitochondria relationship?

Inflammation functions as both consequence and amplifier of stress-induced mitochondrial dysfunction, creating reinforcing pathological loops. Damaged mitochondria release their contents—particularly mitochondrial DNA—into circulation where these molecules activate innate immune receptors, triggering inflammatory cytokine production. Chronic stress induces gradual glucocorticoid resistance, diminishing the anti-inflammatory effects of cortisol whilst pro-inflammatory mediators accumulate. These inflammatory molecules further impair mitochondrial function through multiple mechanisms including oxidative damage, dysregulated calcium handling, and altered gene expression. The observation that mitochondrial respiratory capacity correlates inversely with systemic inflammatory markers highlights this integrated relationship.

Are there biomarkers that can measure mitochondrial stress in humans?

Several biomarkers provide indirect assessment of mitochondrial function and stress in humans, though none comprehensively captures all aspects of mitochondrial health. Circulating cell-free mitochondrial DNA (ccf-mtDNA) measured in blood correlates with mitochondrial stress and inflammatory conditions, with elevated levels documented in depression, anxiety disorders, and following significant stress exposure. Mitochondrial DNA copy number in blood cells provides another accessible marker, though interpretation requires consideration of cell-type composition. Systemic markers including oxidative stress indicators and inflammatory cytokines indirectly reflect mitochondrial dysfunction. More direct functional assessment requires tissue biopsies or specialised techniques such as high-resolution respirometry, limiting clinical applicability. Development of non-invasive, comprehensive mitochondrial assessment tools remains an active area of research.