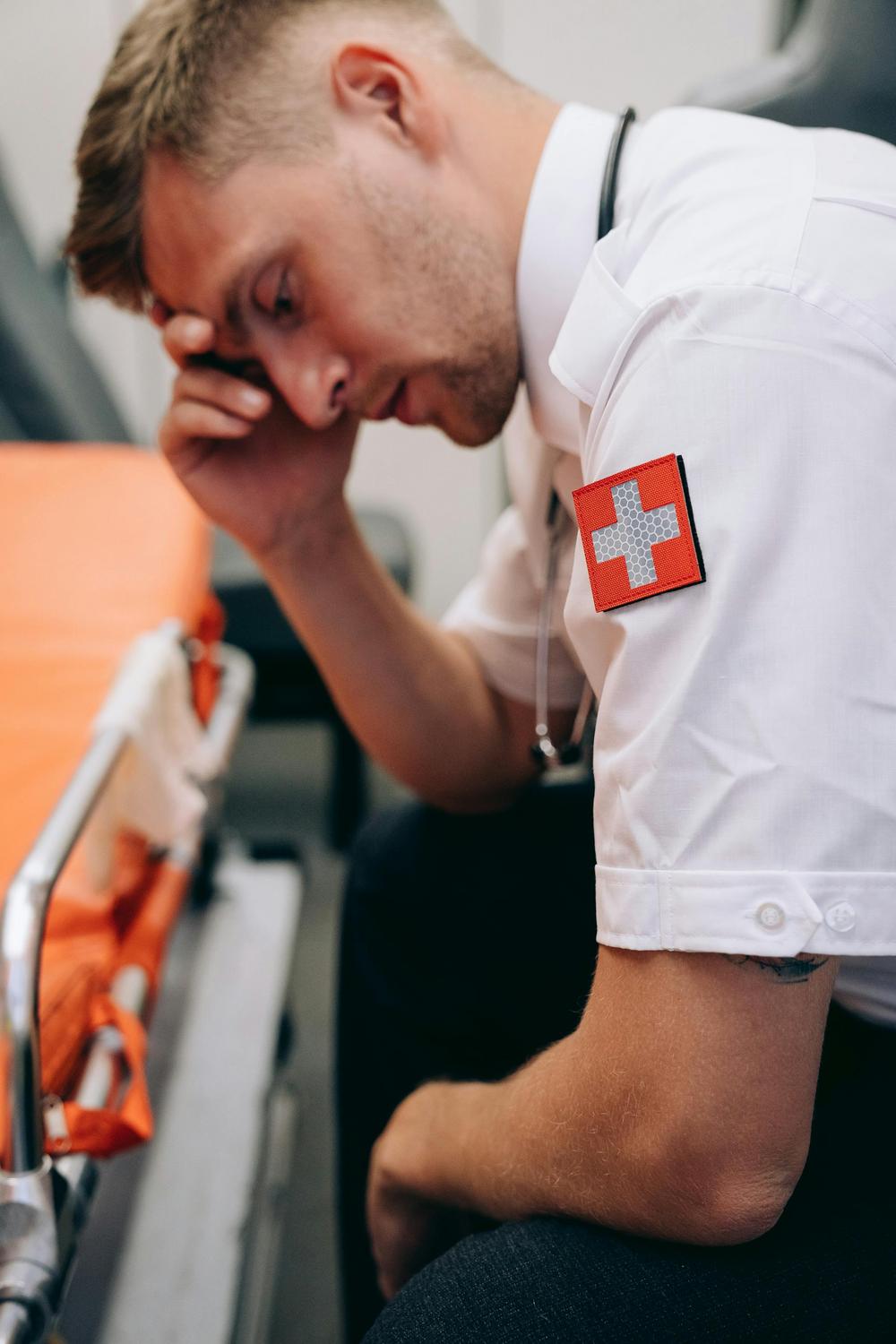

The nurse who can no longer muster empathy for her patients. The therapist who dreads Monday mornings. The emergency responder who lies awake replaying traumatic scenes. These aren’t signs of weakness or poor character—they’re manifestations of compassion fatigue, a serious occupational hazard affecting an estimated 16-85% of healthcare workers globally. In 2026, as Australia’s healthcare system continues to grapple with workforce sustainability challenges, understanding this phenomenon has never been more critical. Compassion fatigue represents not merely workplace stress, but a profound depletion that occurs when caring itself becomes the source of harm. For those who dedicate their lives to alleviating suffering, the very qualities that make them exceptional—empathy, dedication, emotional availability—can paradoxically render them most vulnerable to this debilitating condition.

What Exactly Is Compassion Fatigue and How Does It Differ from Burnout?

Compassion fatigue is defined as a state of exhaustion and dysfunction—biologically, psychologically, and socially—resulting from prolonged exposure to compassion stress. Often termed “the cost of caring,” this condition has been recognised by researchers since the mid-1990s as an occupational hazard inherent to helping professions.

The phenomenon comprises two distinct but interconnected components that converge to create its distinctive profile. The first component, secondary traumatic stress, occurs when healthcare professionals experience trauma indirectly through exposure to others’ suffering without directly experiencing the traumatic event themselves. This exposure can trigger symptoms that mirror post-traumatic stress disorder, including intrusive thoughts, nightmares, avoidance behaviours, and hypervigilance. The second component, burnout, develops from chronic workplace stress and manifests as emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation, and a diminished sense of personal accomplishment.

What distinguishes compassion fatigue from simple burnout is both the speed of onset and the mechanism of development. Whilst burnout typically evolves gradually over months or years through cumulative organisational stress, compassion fatigue can emerge rapidly—sometimes after a single intensely traumatic case. The critical distinction lies in its genesis: compassion fatigue stems specifically from empathetic engagement with others’ suffering, meaning those with greater capacity for empathy paradoxically face heightened risk.

The Professional Quality of Life (ProQOL) Scale, the gold standard assessment tool in this field, measures these components alongside compassion satisfaction—the positive feelings derived from helping effectively—which serves as a crucial protective factor against the negative dimensions of professional caregiving.

Who Is Most Vulnerable to Developing Compassion Fatigue?

The epidemiological landscape of compassion fatigue reveals both concerning prevalence rates and identifiable risk patterns across healthcare sectors. Nurses consistently demonstrate the highest vulnerability, with 80-86% reporting moderate to high levels of compassion fatigue. Emergency room nurses face particularly acute risk, with 86% meeting diagnostic criteria, whilst 82% report moderate to high burnout and 85% experience secondary traumatic stress.

Among physicians, burnout rates ranged from 40-54% in pre-pandemic periods, though these figures escalated dramatically to 76% during the June-September 2020 period. Mental health professionals face their own burden, with approximately 40% of psychiatrists reporting clinical depression. Specialty areas involving end-of-life care, paediatric patients, or high-acuity settings demonstrate elevated prevalence, with 78% of hospice nurses at moderate to high risk and similar patterns observed among oncology nursing staff.

The global picture reflects considerable geographical variation, with a 2024 meta-analysis revealing that 70% of healthcare workers in Sub-Saharan Africa experience compassion fatigue—a rate that increased from 66% pre-COVID-19 to 74% during the pandemic. These statistics underscore the condition’s universal nature whilst highlighting how systemic and resource-related factors can amplify vulnerability.

Risk Factors That Amplify Vulnerability

Individual susceptibility to compassion fatigue emerges from complex interactions between personal characteristics and work conditions. Contrary to conventional assumptions that senior professionals suffer disproportionately, research demonstrates that younger age and early career professionals actually face elevated risk. Female practitioners show higher rates across multiple studies, whilst those with previous personal trauma history or mental health challenges experience compounded vulnerability.

Organisational factors play an equally critical role in determining who develops compassion fatigue. High workload intensity, extensive work hours exceeding 80 hours weekly, inadequate rest periods, and chronic understaffing create fertile ground for this condition to flourish. Poor managerial support, workplace violence, and what researchers term a “culture of silence”—where traumatic events aren’t discussed openly—further elevate risk. Ethical dilemmas and moral distress, particularly when professionals feel unable to provide care aligned with their values, contribute substantially to compassion fatigue development.

The paradox of compassion itself emerges as a significant predictor: those with greater empathetic capacity and emotional investment in patient outcomes face heightened vulnerability precisely because of these admirable qualities. This reality underscores that compassion fatigue represents a hazard of caring deeply, not a personal failing.

How Does Compassion Fatigue Manifest Across Different Dimensions?

The symptomatology of compassion fatigue extends across emotional, physical, behavioural, and relational domains, creating a constellation of signs that can be both subtle in onset and devastating in impact. Understanding these manifestations enables earlier recognition and intervention.

Emotional and Psychological Dimensions

Emotionally, compassion fatigue manifests as pervasive exhaustion that one researcher described as “feeling fatigued in every cell of your being.” This extends beyond physical tiredness to encompass emotional numbing and a diminished capacity to feel compassion or empathy—what might be termed a loss of the ability to nurture. Affected individuals report persistent feelings of hopelessness, powerlessness, and inadequacy, alongside anxiety, depression, and cynicism about their work and its impact. Professional confidence erodes, replaced by self-doubt and questioning of career choices. The sense of not being able to “make a difference” pervades their professional identity, whilst guilt and shame about these emotional responses create additional psychological burden.

Physical Manifestations

The somatic expression of compassion fatigue includes chronic fatigue unrelieved by rest, sleep disturbances ranging from insomnia to hyperinsomnia, and nightmares with traumatic content. Cardiovascular symptoms such as heart palpitations, chest pain, and elevated blood pressure occur alongside gastrointestinal distress, headaches, muscle tension, and frequent illness reflecting compromised immune function. These physical symptoms both reflect and exacerbate the condition, creating vicious cycles that further impair functioning.

Behavioural and Performance Changes

Behaviourally, compassion fatigue drives withdrawal and social isolation from colleagues, family, and friends. Work performance deteriorates through increased absenteeism, presenteeism (attending work whilst ineffective), memory lapses, impaired decision-making, and increased medical errors. Communication quality declines, workplace conflicts increase, and affected individuals may become overly task-focused rather than maintaining patient-centred approaches. In severe cases, substance use as self-medication and even suicidal ideation may emerge.

| Compassion Fatigue Symptom Categories | Key Manifestations | Impact on Professional Function |

|---|---|---|

| Emotional/Psychological | Emotional exhaustion, reduced empathy, hopelessness, anxiety, depression | Diminished patient engagement, loss of professional satisfaction, increased ethical distress |

| Physical | Chronic fatigue, sleep disturbances, cardiovascular symptoms, gastrointestinal issues, frequent illness | Reduced stamina, increased sick leave, compromised clinical decision-making capacity |

| Behavioural | Social withdrawal, increased absenteeism, memory problems, substance use risk | Decreased work productivity, increased medical errors, poor communication |

| Relational | Interpersonal conflict, emotional unavailability, loss of interest in relationships | Work-home conflict, relationship deterioration, professional isolation |

What Are the Broader Consequences of Unaddressed Compassion Fatigue?

The ramifications of compassion fatigue extend far beyond individual suffering, creating cascading effects across healthcare systems and patient populations. For the affected professional, mental health deterioration progresses, with increased risk of depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Job satisfaction plummets, contributing to higher turnover and premature career exit from helping professions at precisely the time when healthcare workforce sustainability has become critical. The long-term physical health consequences include elevated risk for cardiovascular disease, obesity, diabetes, and gastrointestinal conditions—sequelae of sustained physiological stress responses.

Patient care quality suffers measurably when providers experience compassion fatigue. Research demonstrates reduced patient satisfaction, increased medical errors, higher infection rates, and in critical care settings, increased patient mortality. Therapeutic relationships weaken as the empathetic connection that underpins effective care erodes. Clinical decision-making quality deteriorates, potentially contributing to preventable adverse events and complications. These patient safety implications transform compassion fatigue from a personal crisis into a public health concern.

Healthcare organisations bear substantial economic and operational consequences. Staff turnover necessitates costly recruitment and training, whilst sick leave, presenteeism, and reduced productivity affect the bottom line. Workers’ compensation claims related to psychological injury increase, and workplace safety issues proliferate. Team morale and cohesion suffer, potentially perpetuating conditions that foster compassion fatigue in remaining staff members. With an estimated global shortage of 13 million healthcare workers in the post-pandemic era, the attrition caused by compassion fatigue exacerbates an already critical workforce crisis.

At the systemic level, widespread compassion fatigue compromises healthcare system effectiveness and population health outcomes. Australia’s context is particularly relevant here, with mental health challenges affecting 32.4% of nurses for depression and 41.2% for anxiety and stress—figures that threaten the sustainability of healthcare delivery across the nation.

How Can Compassion Fatigue Be Prevented and Managed Effectively?

Evidence-based prevention and management of compassion fatigue requires interventions at both individual and organisational levels, with the most effective approaches addressing both dimensions simultaneously.

Individual-Level Strategies with Demonstrated Effectiveness

Structured resilience training programmes represent one of the most robustly supported individual interventions. Research demonstrates that five-week programmes with 90-minute weekly sessions significantly reduce secondary traumatic stress whilst increasing compassion satisfaction, with benefits maintained at three to six-month follow-up. These programmes build psychological flexibility, adaptive coping strategies, and connection to values-based living.

Mindfulness-based interventions have garnered moderate to strong evidence for effectiveness. Programmes ranging from eight to twelve hours total duration show measurable improvements in burnout and secondary traumatic stress. Notably, shorter programmes incorporating mindfulness, yoga, and relaxation techniques may be as effective as more intensive interventions, particularly when delivered on-site during work hours to enhance accessibility and completion rates.

Comprehensive educational interventions combining interactive seminars with multimedia resources and practical skill-building demonstrate particularly strong outcomes. Four-hour intensive sessions supplemented with take-home materials have shown 10% increases in compassion satisfaction, 34% reductions in burnout symptoms, and 19% decreases in secondary traumatic stress. The multi-component nature of these interventions—addressing knowledge, skills, and resources simultaneously—appears critical to their success.

Foundational self-care practices, whilst less studied in isolation, form the bedrock of prevention. These include 7-9 hours of quality sleep nightly, regular physical activity several times weekly, balanced nutrition, and maintenance of work-life boundaries. Spiritual practices, social connection, and engagement in hobbies outside of work provide restorative experiences that buffer against the depleting effects of compassion stress. Professional counselling and peer support systems offer additional protective resources.

Organisational Interventions That Create Systemic Change

Structural workplace modifications represent powerful preventive measures. Adequate staffing levels and appropriate patient-to-staff ratios emerge as critical variables—understaffing consistently predicts compassion fatigue development. Reasonable work hours, rotating schedules that ensure recovery between high-stress shifts, and protected time for breaks create conditions that support rather than deplete caregivers.

Leadership and cultural factors prove equally significant. Supervisory support through regular check-ins, recognition and appreciation of staff efforts, and management modelling of healthy practices establish norms that legitimise self-care. Creating psychologically safe spaces for discussing stressful events and normalising mental health challenges reduces the stigma that often prevents help-seeking. Addressing workplace incivility, violence, and interpersonal conflicts whilst ensuring fair and equitable treatment policies fosters environments where professionals can thrive.

Professional support systems institutionalise assistance for struggling staff. Peer support groups, formal debriefing sessions following traumatic events, clinical supervision, mentorship programmes, and accessible employee assistance programmes provide safety nets. On-site or virtual mental health counselling removes barriers to accessing professional support.

Educational initiatives at the organisational level reduce compassion fatigue through awareness-building. Staff education programmes about compassion fatigue recognition and management, coupled with training in stress management techniques, communication skills, and trauma-informed care, equip professionals with tools for self-monitoring and early intervention. Integration of compassion fatigue content into graduate training programmes and continuing professional development ensures emerging professionals enter practice with protective knowledge.

Environmental supports such as relaxation rooms, on-site wellness activities, and wellness programmes addressing nutrition, fitness, and health screening demonstrate organisational commitment to staff wellbeing whilst providing practical resources for recovery.

Evidence-Based Comprehensive Programmes

Several structured programmes have demonstrated particular effectiveness. The Accelerated Recovery Programme, consisting of five sessions addressing resiliency, self-care, intentionality, self-regulation, and perceptual maturation, showed significant improvements in burnout and compassion satisfaction, with participants reporting increased empowerment and self-worth. The THRIVE Programme, combining an eight-hour retreat with six weeks of facilitated group study, demonstrated statistically significant increases in resilience and decreases in both burnout and secondary traumatic stress sustained at six-month follow-up.

What Protective Factors Buffer Against Compassion Fatigue?

Compassion satisfaction—the positive feelings and sense of fulfilment derived from helping others effectively—emerges as perhaps the most powerful protective factor against compassion fatigue. Research reveals strong negative correlations between compassion satisfaction and both burnout (r = -0.71 to -0.732) and secondary traumatic stress, suggesting that cultivating this dimension of professional experience provides robust buffering.

Several factors enhance compassion satisfaction and thereby offer protection. Years of professional experience correlate positively with compassion satisfaction, suggesting that seasoned practitioners develop resources and perspectives that sustain them. Higher job satisfaction, recognition and appreciation from supervisors, and a sense of making meaningful differences in patients’ lives all strengthen this protective dimension. Supportive work environments, adequate staffing and resources, professional autonomy, and meaningful collegial relationships foster the conditions under which compassion satisfaction flourishes. Connection to personal values in work and witnessing patient improvement and recovery provide the rewards that make the emotional labour of caring sustainable.

This protective dimension underscores an important reality: the solution to compassion fatigue is not to care less, but to create conditions—both internal and external—that allow caring to be regenerative rather than depleting. Organisations and individuals that prioritise compassion satisfaction as actively as they address risk factors adopt a more complete and ultimately more effective approach to workforce wellbeing.

Moving Forward: A Call for Systemic Recognition

Understanding compassion fatigue as an occupational hazard rather than personal weakness represents a fundamental shift in how helping professions conceptualise caregiver wellbeing. The evidence is unequivocal: compassion fatigue affects the majority of healthcare workers at some point in their careers, with prevalence rates reaching as high as 86% in certain specialties. This is not a problem of individual resilience deficits but a predictable consequence of working conditions that systematically deplete those who care.

Australia’s healthcare landscape in 2026 reflects the enduring impacts of recent global health crises and ongoing workforce challenges. With AHPRA-registered professionals comprising the backbone of healthcare delivery, addressing compassion fatigue is not merely about supporting individual practitioners—though this is crucial—but about ensuring the sustainability and effectiveness of the entire healthcare system. The economic costs of untreated compassion fatigue, measured in turnover, errors, reduced productivity, and compromised patient outcomes, justify substantial investment in prevention and management.

The path forward requires multi-level commitment. Healthcare organisations must move beyond rhetoric about workforce wellbeing to implement evidence-based structural changes: adequate staffing, reasonable work hours, supportive leadership, accessible mental health resources, and cultures that normalise self-care and help-seeking. Educational institutions must integrate compassion fatigue awareness and self-care skills into professional training from the outset. Individual practitioners must recognise the early signs of compassion fatigue in themselves and colleagues, viewing help-seeking as professional responsibility rather than admission of weakness.

Compassion fatigue need not be an inevitable consequence of caring professionally. With informed awareness, evidence-based interventions, and systemic commitment to caregiver wellbeing, the helping professions can preserve the very quality that makes them effective—the capacity to connect with and respond compassionately to human suffering—whilst protecting those who embody this capacity from the costs that caring can exact.

Can compassion fatigue develop suddenly, or is it always a gradual process?

Unlike burnout, which typically develops gradually over months or years, compassion fatigue can emerge rapidly—sometimes following a single intensely traumatic case or exposure. Secondary traumatic stress, one of compassion fatigue’s key components, may appear suddenly after witnessing or hearing about particularly distressing patient situations. However, the condition can also accumulate slowly through repeated exposure to others’ suffering. The speed of onset often depends on the intensity of trauma exposure, individual vulnerability factors, and the presence or absence of protective factors such as social support and adequate recovery time between stressful events.

How is compassion fatigue officially assessed in healthcare settings?

The Professional Quality of Life (ProQOL) Scale Version 5 serves as the standard validated assessment tool for compassion fatigue. This 30-item self-report instrument measures three domains: compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress. It is freely available online with interpretation guidelines and established norms, making it accessible for both individual self-assessment and organisational screening programmes. Healthcare facilities may implement annual ProQOL screenings during performance reviews or educational sessions to monitor workforce wellbeing and identify professionals requiring additional support or intervention.

Are certain healthcare specialties more at risk for compassion fatigue than others?

Research consistently identifies emergency departments, intensive care units, oncology, palliative care, and mental health services as high-risk environments for compassion fatigue development. Emergency room nurses demonstrate particularly high prevalence rates, with 86% meeting diagnostic criteria. While these specialties share common characteristics such as frequent exposure to death and high-acuity situations, compassion fatigue can develop in any role involving sustained empathetic engagement with suffering.

What’s the difference between needing a break and experiencing true compassion fatigue?

Normal occupational fatigue typically responds to rest—a weekend off, a holiday, or reduced work hours—while compassion fatigue involves persistent symptoms that don’t resolve with standard rest. Key differentiating features include emotional numbing, intrusive thoughts about traumatic events, chronic physical symptoms such as fatigue and sleep disturbances, and a fundamental questioning of one’s career choice. If these symptoms persist despite adequate rest, they may indicate compassion fatigue, which requires professional assessment and intervention.

Can you recover from compassion fatigue, or does it cause permanent damage?

Compassion fatigue is treatable and recovery is absolutely possible, though the timeline varies depending on severity and the interventions employed. Evidence-based programmes such as structured resilience training, mindfulness-based interventions, professional counselling, and comprehensive organisational support can significantly reduce symptoms. Early intervention is key, and many professionals who recover from compassion fatigue report enhanced self-awareness and a renewed commitment to sustainable practice patterns.