In an era where mental health challenges have reached unprecedented levels, with anxiety and depression affecting millions of Australians, an ancient practice is emerging as a beacon of hope in modern healthcare settings. Mindfulness—a concept that bridges millennia-old wisdom with cutting-edge neuroscience—offers a pathway to mental clarity and emotional resilience that feels both revolutionary and timeless. Yet despite its growing prominence in hospitals, clinics, and therapeutic practices across Australia, many people remain uncertain about what mindfulness truly entails and how this profound practice evolved from monastery halls to medical centres.

What Exactly Is Mindfulness and How Do We Define It?

Mindfulness represents a multifaceted concept that has been interpreted across various cultural, spiritual, and scientific contexts throughout history. At its most fundamental level, mindfulness refers to a particular way of paying attention that involves “paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally.” This definition, popularised by Jon Kabat-Zinn, captures the essential elements that distinguish mindful awareness from ordinary consciousness: intentionality, present-moment focus, and an attitude of acceptance rather than judgment.

The etymological roots of mindfulness trace back to the Pali word “sati,” which encompasses multiple dimensions of awareness including moment-to-moment awareness of present events and remembering to be aware of something. In the Buddhist tradition, sati encompasses awareness, alertness, and attention, but specifically refers to a sustained quality of consciousness that remains present with whatever arises in experience.

Contemporary psychological science has sought to provide more precise operational definitions of mindfulness that can support empirical research and clinical applications. Recent comprehensive reviews identify core components that include present-centred awareness and bare attention to body sensations, affective states, cognitive and emotional phenomena, and the external environment, all maintained with an allowing and equanimous attitude. This definition attempts to bridge the gap between traditional Buddhist conceptualisations and the requirements of scientific measurement.

| Core Components of Mindfulness | Traditional Buddhist Context | Modern Scientific Context |

|---|---|---|

| Present-moment awareness | Sati (mindfulness/awareness) | Sustained attention to immediate experience |

| Non-judgmental observation | Upekkha (equanimity) | Acceptance without evaluation |

| Intentional attention | Sammā-sati (right mindfulness) | Purposeful direction of consciousness |

| Meta-cognitive awareness | Sati-sampajañña (clear comprehension) | Awareness of awareness itself |

The concept of “bare attention” represents a crucial aspect of mindfulness that distinguishes it from other forms of mental training. Bare attention refers to the capacity to observe experience directly without immediately categorising, analysing, or responding to what is observed. This quality of awareness allows individuals to develop a different relationship with their thoughts, emotions, and sensations, creating space between stimulus and response that can interrupt automatic patterns of reactivity.

Essential attitudes that shape how attention is applied in mindfulness include non-judgment, patience, beginner’s mind, trust, non-striving, acceptance, and letting go. Non-judgment refers to observing experience without immediately evaluating it as good or bad, right or wrong. Beginner’s mind involves approaching each moment with fresh perspective, free from preconceptions based on past experience. Acceptance acknowledges what is actually present in experience before deciding how to respond.

Mindfulness also involves what researchers term “decentering” or “cognitive defusion”—the ability to observe thoughts and emotions as mental events rather than absolute truths or commands for action. This shift in perspective allows individuals to develop a more spacious relationship with their internal experience, reducing the tendency to become identified with particular thoughts or emotions. Decentering appears to be a key mechanism through which mindfulness promotes psychological wellbeing.

Where Did Mindfulness Originate and What Are Its Ancient Roots?

The historical foundations of mindfulness are deeply embedded in the Buddhist tradition, where it emerged as a central component of the path to enlightenment and liberation from suffering. In early Buddhist teachings, mindfulness (sati) is identified as one of the seven factors of enlightenment and constitutes the seventh element of the Noble Eightfold Path as “right mindfulness.” This positioning within the core structure of Buddhist doctrine indicates that mindfulness was understood not as a peripheral technique but as a fundamental capacity necessary for spiritual development and psychological transformation.

The earliest systematic presentation of mindfulness practice appears in the Satipatthana Sutta, contained within the Pali Canon and considered one of the most important discourses attributed to the historical Buddha. This text outlines the “four foundations of mindfulness”: mindfulness of the body (including breath awareness and bodily sensations), mindfulness of feelings (the immediate pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral quality of experience), mindfulness of mind (observing the states and qualities of consciousness), and mindfulness of mental objects (awareness of thoughts, emotions, and mental formations).

The practice of Vipassana, or insight meditation, represents one of the most direct expressions of mindfulness as conceived in early Buddhism. Vipassana, meaning “to see things as they really are,” focuses on developing clear comprehension of the changing nature of all phenomena, leading to insight into the three characteristics of existence: impermanence, suffering, and non-self. This practice emphasises sustained attention to the arising and passing away of physical sensations, thoughts, and emotions, cultivating direct experiential understanding of the transient nature of all conditioned phenomena.

According to historical accounts, the practice of Vipassana meditation may have been largely lost in the Theravada world by the early 1800s, with perhaps only a handful of practitioners maintaining the tradition. The modern revival of Vipassana began in the late 1800s and early 1900s through the work of key figures who reconstructed the practice based on scriptural descriptions and practical experimentation. This historical development illustrates how meditation practices require continuous transmission and adaptation to remain vital across generations.

Different schools of Buddhism developed distinct approaches to mindfulness whilst maintaining core principles. Theravada Buddhism emphasises Vipassana and Samatha (concentration) meditation, focusing on developing insight through systematic observation of mental and physical phenomena. Mahayana Buddhism, including Zen and Pure Land traditions, developed alternative approaches that often emphasise compassion and the bodhisattva ideal. Zen meditation (zazen) represents a particular form of mindfulness practice involving “just sitting” with open awareness, allowing whatever arises in experience to be present without focusing on specific objects of meditation.

The transmission of Buddhist mindfulness practices throughout Asia led to cultural adaptations that influenced local spiritual traditions whilst maintaining core contemplative principles. In China, Buddhist meditation practices merged with Taoist philosophy to create distinctly Chinese forms of contemplative practice. In Japan, Zen Buddhism developed unique aesthetic and cultural expressions whilst preserving essential meditation techniques.

How Did Mindfulness Transform From Eastern Practice to Western Medicine?

The introduction and adaptation of mindfulness practices in Western contexts represents one of the most significant cross-cultural translations of contemplative techniques in modern history. This process began during the 1950s and 1960s when Buddhism started gaining footholds in American culture, initially through the Beat Movement and subsequently influencing counterculture movements. The initial wave of interest was largely cultural and philosophical, with figures exploring Buddhist ideas as alternatives to conventional Western approaches to meaning and consciousness.

The systematic scientific study of mindfulness began in the 1970s and reached a crucial turning point with the work of Jon Kabat-Zinn at the University of Massachusetts Medical School. Kabat-Zinn, who had training in both Zen and Theravada meditation traditions, recognised the potential for Buddhist contemplative practices to address medical and psychological problems within a secular, evidence-based framework. His development of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) in the late 1970s represented a pioneering effort to extract essential elements of Buddhist mindfulness practices whilst removing their explicitly religious and cultural contexts.

The creation of MBSR involved careful consideration of how to present ancient practices in ways acceptable and accessible to Western medical patients and healthcare providers. Strategic decisions emphasised the practical benefits of mindfulness rather than spiritual dimensions, focusing on stress reduction, pain management, and improved quality of life. This approach required developing new language and conceptual frameworks that could communicate the essence of mindfulness without relying on Buddhist terminology or cosmology.

The eight-week MBSR program combines mindfulness meditation, body awareness exercises, and gentle yoga to help participants develop skills for managing stress, pain, and illness. The curriculum includes both formal meditation practices (such as sitting meditation and body scans) and informal practices that integrate mindfulness into daily activities. Group discussions and home practice assignments provide additional support for developing and sustaining mindfulness skills outside clinical settings.

Establishing scientific credibility through rigorous research methodologies was crucial to Western adaptation. Early randomised controlled trials evaluated MBSR effectiveness for chronic pain management, finding significant improvements in pain intensity, psychological distress, and quality of life among participants. These studies provided foundations for growing research documenting benefits of mindfulness-based interventions across wide ranges of medical and psychological conditions.

The distinction between “mindfulness” and “meditation” in Western contexts reflects this cultural adaptation and scientific validation process. Whilst terms are sometimes used interchangeably, “mindfulness” has designated practices that have been secularised and subjected to scientific study, whereas “meditation” often refers to practices within their original religious contexts. This linguistic distinction has allowed mindfulness integration into healthcare settings where explicitly religious practices might not be appropriate.

What Does Scientific Research Reveal About Mindfulness Benefits?

The scientific investigation of mindfulness has produced substantial research demonstrating effects on multiple dimensions of human health and functioning. This research encompasses psychological outcomes, neurobiological changes, and physiological benefits, providing converging evidence for the therapeutic potential of mindfulness practices. The methodological rigour of this research has contributed to mindfulness acceptance within evidence-based healthcare and established clear protocols for clinical applications.

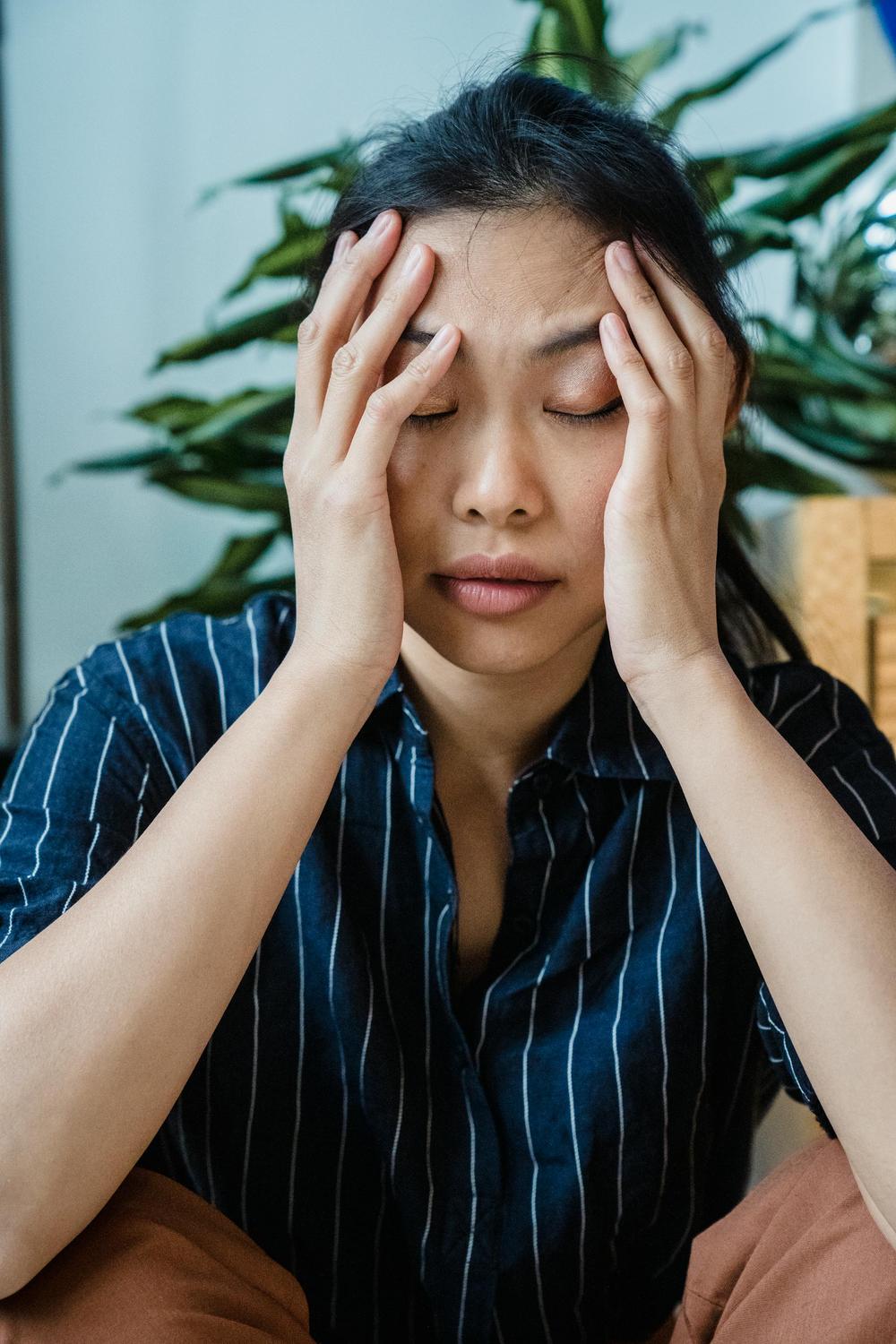

Psychological research consistently demonstrates that mindfulness practices can produce significant improvements in mental health outcomes. Studies show that mindfulness-based interventions can reduce symptoms of anxiety, depression, and psychological distress whilst enhancing overall wellbeing and life satisfaction. Comprehensive reviews of mindfulness research found these interventions bring about various positive psychological effects, including increased subjective wellbeing, reduced psychological symptoms, and enhanced emotional regulation.

The reduction of rumination represents one of the most consistently documented benefits of mindfulness practice. Rumination involves repetitive, self-focused thinking about problems, distress, and negative experiences, and is strongly associated with depression and anxiety disorders. Research shows mindfulness training can significantly reduce rumination by teaching individuals to observe thoughts without becoming caught up in their content, interrupting cognitive patterns that maintain emotional distress.

Attention and cognitive flexibility represent another domain where mindfulness demonstrates clear benefits. Studies comparing experienced meditators with non-meditators found regular mindfulness practice associated with enhanced cognitive flexibility, improved sustained attention, and better ability to focus attention whilst suppressing distracting information. These cognitive improvements appear to result from systematic training in attention regulation during formal mindfulness practice.

Neuroscientific research has provided important insights into brain changes associated with mindfulness practice. Studies comparing brains of experienced meditators with non-practitioners found structural differences in brain regions associated with attention, interoception, and emotional processing. These differences include increased thickness in the prefrontal cortex and right anterior insula, regions involved in attention and body awareness, as well as increased grey matter concentration in areas active during meditation practice.

Neuroimaging studies examining mindfulness training effects on brain activity patterns found associations with increased activation in brain areas involved in processing emotional and attentional information, including the rostral anterior cingulate cortex and dorsomedial prefrontal cortex. These findings suggest mindfulness training induces neuroplastic changes supporting improved attention, awareness, and emotional regulation at brain structure and function levels.

The physiological benefits of mindfulness practice extend beyond the brain to include improvements in immune function, cardiovascular health, and inflammatory processes. Research documents that mindfulness practice can enhance immune functioning, evidenced by improved antibody responses to vaccination and reduced inflammatory markers. Studies also found mindfulness can help lower blood pressure, improve sleep quality, and reduce chronic pain, suggesting broad effects on multiple physiological systems.

How Is Mindfulness Currently Applied in Healthcare and Clinical Settings?

The integration of mindfulness into contemporary healthcare represents a significant paradigm shift bridging contemplative wisdom with evidence-based medicine. Modern clinical applications of mindfulness span diverse medical specialities and treatment settings, from primary care clinics to specialised pain management centres, psychiatric facilities, and integrative medicine programmes. This widespread adoption reflects growing recognition that mindfulness addresses fundamental aspects of human suffering that conventional medical approaches may not adequately address.

Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction remains the most widely implemented and researched mindfulness intervention in healthcare settings. The programme’s standardised eight-week format provides a reliable framework adapted for various populations and conditions whilst maintaining core elements ensuring therapeutic integrity. Healthcare institutions worldwide have established MBSR programmes serving patients with chronic pain, anxiety disorders, depression, cancer, heart disease, and other conditions where stress plays significant roles in symptom severity and treatment outcomes.

The application of mindfulness in chronic pain management represents one of the most well-established clinical uses. Research consistently demonstrates mindfulness training can help individuals develop different relationships with pain that reduce suffering even when physical sensations remain present. Patients learn to observe pain sensations with acceptance rather than resistance, reducing emotional and psychological amplification often accompanying chronic pain conditions.

Mental health applications of mindfulness have expanded rapidly, with mindfulness-based interventions now recognised as evidence-based treatments for several psychiatric conditions. Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy has received particular attention for effectiveness in preventing depressive relapse, with research showing it can reduce relapse rates by approximately 43% in individuals with recurrent depression. The programme teaches individuals to recognise early warning signs of depression and respond with mindfulness skills rather than rumination patterns typically precipitating depressive episodes.

Healthcare professionals themselves increasingly turn to mindfulness practices to address burnout, compassion fatigue, and the psychological demands of medical practice. Research indicates mindfulness training for healthcare providers can reduce emotional reactivity, enhance self-compassion, improve communication skills, and increase job satisfaction. Programmes designed specifically for healthcare professionals often emphasise mindfulness applications that can be integrated into clinical settings.

The integration of mindfulness into paediatric healthcare has opened new avenues for supporting children and adolescents facing medical challenges. Age-appropriate mindfulness programmes help young patients develop coping skills for managing anxiety, pain, and treatment-related distress whilst supporting emotional resilience during critical developmental periods. School-based mindfulness programmes have also shown promise for improving attention, emotional regulation, and social skills among children and adolescents.

Digital health applications have created new opportunities for delivering mindfulness training at scale through smartphone apps, online programmes, and virtual reality environments. These technological innovations address barriers to accessing traditional in-person mindfulness programmes whilst providing personalised features adapting to individual needs and preferences. Research on mindfulness apps shows they can produce meaningful benefits when used consistently, though effectiveness varies significantly depending on app design and user engagement.

What is the difference between mindfulness and meditation?

Mindfulness refers specifically to a quality of awareness characterised by present-moment attention with an accepting, non-judgmental attitude, whilst meditation encompasses a broader range of contemplative practices. Mindfulness can be practiced both formally through sitting meditation and informally throughout daily activities, whereas meditation typically refers to dedicated periods of contemplative practice.

How long does it take to see benefits from mindfulness practice?

Research indicates that benefits from mindfulness practice can begin appearing within weeks of regular practice. Studies of eight-week mindfulness programmes consistently show improvements in stress, anxiety, and emotional regulation by programme completion. However, sustained benefits typically require ongoing practice, with deeper changes often emerging over months and years of consistent engagement.

Is mindfulness appropriate for everyone, or are there contraindications?

Whilst mindfulness is generally safe and beneficial for most people, certain individuals may need modified approaches or additional support. People with severe trauma histories, active psychosis, or certain dissociative conditions may benefit from working with qualified mental health professionals who can adapt mindfulness practices appropriately for their specific needs and circumstances.

Can mindfulness be practiced alongside conventional medical treatments?

Mindfulness is designed to complement rather than replace conventional medical treatments. Research consistently shows that mindfulness enhances the effectiveness of standard medical care whilst reducing side effects and improving quality of life. Always consult with healthcare providers about integrating mindfulness practice with existing treatment plans.

What qualifications should I look for in a mindfulness instructor?

Quality mindfulness instruction requires both formal training and ongoing personal practice. Look for instructors with recognised certifications from established programmes, ongoing professional development, supervision by experienced teachers, and personal mindfulness practice experience. Many healthcare settings employ AHPRA-registered professionals who have completed specialised mindfulness training programmes.