The human capacity to not merely survive adversity but to emerge fundamentally transformed by it represents one of psychology’s most compelling frontiers. Whilst trauma’s immediate aftermath often brings profound distress, emerging research reveals a paradoxical truth: for many individuals, the struggle with highly challenging circumstances can catalyse significant positive psychological change. This phenomenon, termed post-traumatic growth, challenges conventional assumptions about recovery and resilience, offering a more nuanced understanding of how humans adapt to life’s most demanding experiences.

In Australia, where approximately one in three adults will experience a traumatic event during their lifetime, understanding the mechanisms that facilitate growth beyond survival has become increasingly vital. The implications extend beyond individual wellbeing to inform therapeutic approaches, workplace support systems, and community resilience programmes across the nation.

What Exactly Is Post-Traumatic Growth and How Does It Differ from Resilience?

Post-traumatic growth (PTG) describes positive psychological change experienced as a result of struggling with highly challenging life circumstances. Psychologists Richard Tedeschi and Lawrence Calhoun first conceptualised this phenomenon in the mid-1990s, establishing a framework that distinguishes growth from mere recovery or resilience.

Unlike resilience—which refers to the ability to bounce back to one’s pre-trauma baseline—post-traumatic growth represents a transformation that takes individuals beyond their previous level of functioning. The distinction is crucial: resilient individuals return to equilibrium, whilst those experiencing PTG undergo fundamental shifts in their understanding of themselves, their relationships, and their life philosophy.

Research identifies five core domains where post-traumatic growth manifests:

1. Greater appreciation of life: Individuals develop heightened awareness of life’s preciousness and prioritise meaningful experiences over superficial pursuits.

2. More meaningful interpersonal relationships: Trauma survivors often report deeper connections, increased compassion, and greater willingness to express vulnerability with others.

3. Increased personal strength: The recognition that “I survived this” fosters confidence in one’s ability to face future challenges.

4. Recognition of new possibilities: Adversity can open pathways previously unconsidered, leading to career changes, new relationships, or alternative life directions.

5. Spiritual or existential development: Many individuals report enhanced spiritual awareness, regardless of whether this manifests through organised religion or personal philosophy.

It bears emphasising that post-traumatic growth does not eliminate distress or negate suffering. Rather, growth and distress frequently coexist—a duality that distinguishes PTG from simplistic notions of “silver linings” or “everything happening for a reason.”

What Psychological Mechanisms Drive Post-Traumatic Growth?

The pathway from trauma to growth involves complex cognitive and emotional processes that current research continues to illuminate. Understanding these mechanisms provides insight into why some individuals experience significant transformation whilst others struggle with prolonged distress.

Central to post-traumatic growth is the concept of cognitive processing—specifically, how individuals make sense of traumatic experiences that shatter fundamental assumptions about the world. Psychologists refer to these foundational beliefs as “schemas,” and trauma often violates core schemas about safety, predictability, and personal invulnerability.

The dissonance created by this violation necessitates what researchers term “deliberate rumination“—a constructive form of reflection distinct from the intrusive, repetitive thoughts common in acute trauma. Deliberate rumination involves actively searching for meaning, questioning pre-existing beliefs, and reconstructing one’s narrative to accommodate new realities.

Neurobiological research reveals that trauma affects brain regions involved in emotional regulation, memory consolidation, and threat detection. The hippocampus, prefrontal cortex, and amygdala undergo structural and functional changes following traumatic exposure. Importantly, these changes are not uniformly negative; emerging evidence suggests that adaptive neuroplasticity can facilitate growth when supported by appropriate psychological and social factors.

The social environment plays an equally critical role. Supportive relationships provide the context within which cognitive processing can occur safely. Research consistently demonstrates that individuals with access to empathetic listeners, validation of their experiences, and community connection are more likely to experience post-traumatic growth. Conversely, invalidating environments or social isolation can impede the growth process.

Emotional regulation capacity also influences PTG trajectories. The ability to tolerate distress without becoming overwhelmed, whilst simultaneously remaining open to processing painful experiences, creates conditions conducive to transformation. This balance—neither suppressing difficult emotions nor being consumed by them—represents a critical skill that can be cultivated through therapeutic intervention.

How Do Researchers Measure and Study Post-Traumatic Growth?

The scientific study of post-traumatic growth requires rigorous methodology to distinguish genuine transformation from illusions of growth or socially desirable responses. Researchers employ multiple assessment strategies, each with distinct strengths and limitations.

The Post-Traumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI), developed by Tedeschi and Calhoun, remains the most widely utilised instrument. This 21-item questionnaire assesses growth across the five domains previously outlined, asking respondents to indicate the degree of change experienced since their traumatic event. The PTGI has demonstrated robust psychometric properties across diverse populations and cultural contexts.

However, measurement challenges persist. Critics note that retrospective self-reports may be influenced by cognitive biases, including the tendency to reinterpret one’s pre-trauma functioning in ways that exaggerate current growth. To address this limitation, researchers increasingly employ longitudinal designs that assess individuals at multiple time points following trauma, providing more nuanced understanding of growth trajectories over time.

Qualitative research methods complement quantitative approaches by capturing the richness and complexity of individual experiences. In-depth interviews reveal how growth unfolds in lived experience, illuminating processes that standardised instruments might miss. Mixed-methods studies combining both approaches offer the most comprehensive understanding.

Recent advances incorporate physiological and neurobiological markers alongside psychological assessments. Studies examining cortisol patterns, inflammatory markers, and brain imaging data provide objective indices of adaptation that can be correlated with self-reported growth. This multi-level approach strengthens the scientific foundation for understanding PTG.

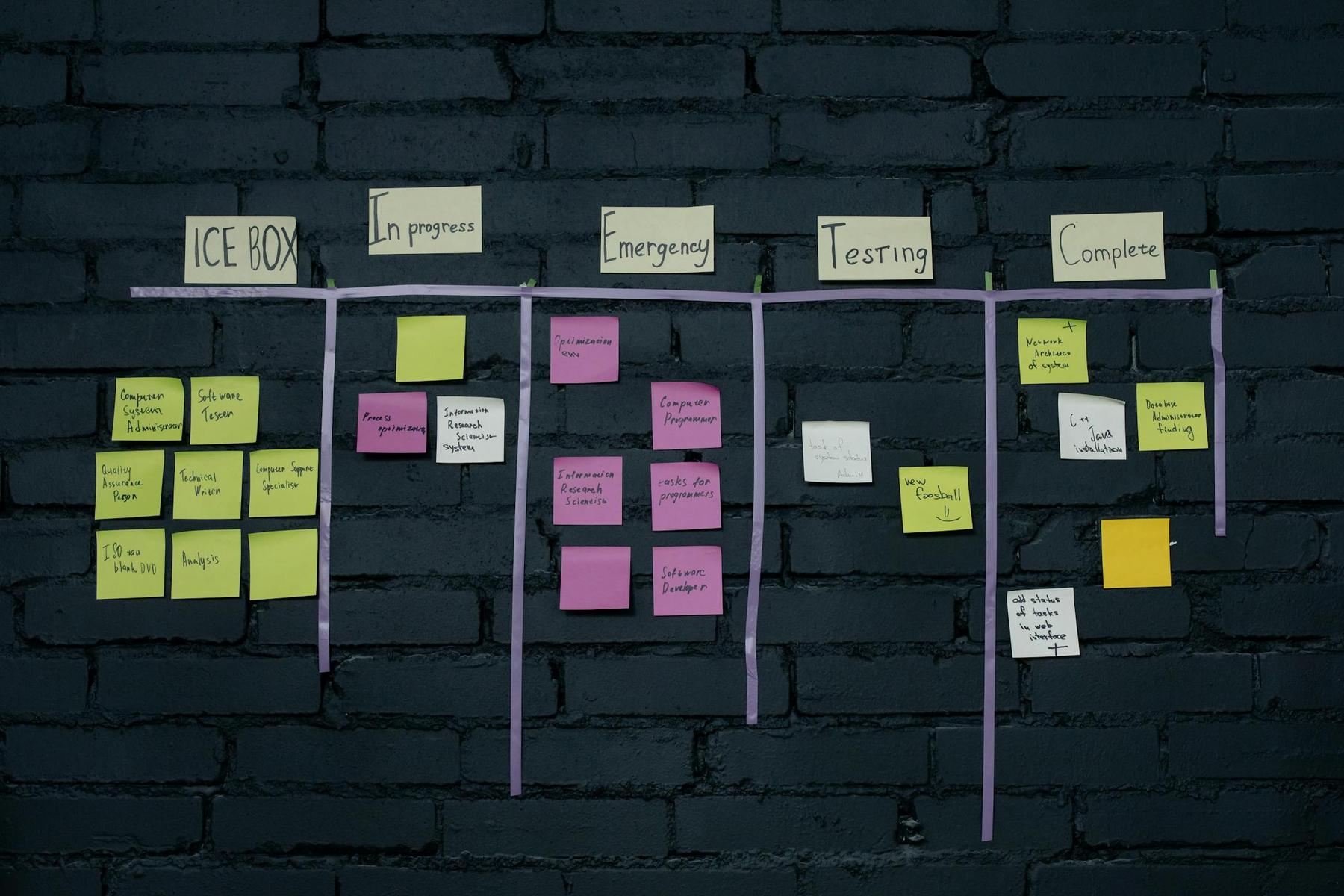

| Assessment Approach | Key Strengths | Primary Limitations | Typical Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| PTGI Questionnaire | Standardised, validated, efficient | Retrospective bias, self-report limitations | Large-scale studies, screening |

| Longitudinal Tracking | Captures temporal dynamics, reduces retrospective bias | Resource-intensive, attrition issues | Research studies, long-term follow-up |

| Qualitative Interviews | Rich contextual data, captures nuance | Time-consuming, difficult to generalise | Exploratory research, theory development |

| Neurobiological Markers | Objective measures, reveals mechanisms | Expensive, correlation vs. causation challenges | Advanced research settings |

What Factors Facilitate or Hinder Post-Traumatic Growth?

Not all individuals exposed to trauma experience subsequent growth, and identifying the factors that facilitate or impede PTG remains a priority for researchers and clinicians. Evidence suggests that both individual characteristics and environmental conditions influence growth trajectories.

Individual factors associated with greater post-traumatic growth include:

Cognitive flexibility: The capacity to consider alternative perspectives and question rigid beliefs facilitates the meaning-making process central to PTG. Individuals who demonstrate cognitive openness more readily reconstruct their worldviews following trauma.

Pre-trauma personality traits: Extraversion, openness to experience, and optimism correlate with higher levels of reported growth, though the relationships are modest and do not preclude growth among individuals without these characteristics.

Previous coping experience: Contrary to intuition, research suggests that individuals with some prior experience managing adversity may be better equipped to navigate traumatic events in ways that promote growth. Complete absence of prior challenge may leave individuals without developed coping resources.

Cultural background: Cultural contexts shape how trauma is interpreted and discussed. Collectivist cultures emphasising communal support and shared meaning-making may facilitate different growth patterns compared to individualist societies prioritising personal autonomy.

Environmental and social factors include:

Quality of social support: The presence of individuals who can provide emotional validation, practical assistance, and opportunities for disclosure strongly predicts post-traumatic growth. Critically, support quality matters more than quantity—a single deeply understanding relationship may prove more beneficial than numerous superficial connections.

Professional support access: Whilst spontaneous growth can occur, access to skilled professionals who facilitate constructive cognitive processing significantly enhances growth likelihood. Therapeutic approaches specifically targeting PTG demonstrate efficacy in controlled trials.

Time since trauma: Post-traumatic growth typically emerges gradually rather than immediately following trauma. Research suggests that growth often becomes evident months or years after the traumatic event, as individuals progress through phases of initial survival, cognitive processing, and eventual integration.

Trauma characteristics: The type, severity, and controllability of traumatic events influence growth potential. Controllable stressors may foster different growth patterns than uncontrollable events. Additionally, traumas that fundamentally challenge core beliefs may paradoxically create greater opportunity for profound transformation.

How Can Understanding Post-Traumatic Growth Inform Professional Practice?

The translation of post-traumatic growth research into clinical and community practice represents an evolving frontier. Professionals across healthcare, psychology, and social services increasingly recognise that trauma treatment extends beyond symptom reduction to encompass growth facilitation.

Contemporary therapeutic approaches incorporate PTG principles by explicitly discussing the possibility of growth with trauma survivors. This conversation normalises the coexistence of distress and positive change, reducing the pressure some individuals feel to “be fine” or “move on” prematurely. Importantly, clinicians emphasise that growth cannot be forced—acknowledging its possibility without creating expectation proves most helpful.

Evidence-based interventions targeting post-traumatic growth employ structured techniques:

Narrative reconstruction: Therapists guide individuals through the process of constructing coherent narratives that integrate traumatic experiences into their broader life story. This process transforms chaotic, fragmented memories into meaningful accounts that facilitate understanding and growth.

Values clarification: Trauma often illuminates what truly matters. Therapeutic work identifying core values and aligning behaviour with these values leverages the clarifying effect trauma can produce.

Gratitude practices: Whilst potentially uncomfortable in trauma’s immediate aftermath, cultivating gratitude for life’s positive aspects—even small ones—can gradually shift perspective towards appreciation, one of PTG’s core domains.

Strengths identification: Explicitly recognising capacities and resources deployed during trauma survival builds awareness of personal strength, another key growth domain.

Meaning-making activities: Journaling, creative expression, and structured reflection exercises facilitate the deliberate rumination associated with growth whilst reducing harmful intrusive thoughts.

Beyond individual therapy, post-traumatic growth research informs peer support programmes, workplace wellness initiatives, and community resilience building. Organisations increasingly recognise that supporting employees through difficult life events—by providing flexible arrangements, normalising help-seeking, and fostering supportive cultures—benefits both individuals and institutional outcomes.

In Australia, where bushfires, floods, and other natural disasters affect communities regularly, PTG principles inform disaster response and recovery programmes. Community-level interventions that facilitate collective meaning-making and mutual support can foster growth at both individual and societal levels.

What Does Current Research Reveal About Long-Term Outcomes?

Longitudinal studies tracking trauma survivors over extended periods provide insight into post-traumatic growth’s durability and long-term implications. These investigations reveal complex patterns that challenge simplistic assumptions about growth’s trajectory and impact.

Research demonstrates that reported post-traumatic growth generally remains stable or increases over time for many individuals, suggesting that PTG represents genuine psychological transformation rather than temporary coping or denial. Studies following individuals for five years or longer post-trauma find that growth levels often increase as individuals gain temporal distance and perspective on their experiences.

However, the relationship between post-traumatic growth and traditional mental health outcomes proves more nuanced than initially assumed. Early research suggested that higher PTG predicted better psychological wellbeing, but subsequent investigations reveal more complex patterns. Some studies find positive correlations between growth and wellbeing, whilst others detect no relationship or even negative associations.

This apparent contradiction reflects the multifaceted nature of post-traumatic adaptation. Growth and distress are not opposite ends of a single spectrum but rather separate dimensions that can coexist. An individual may simultaneously experience profound personal transformation and ongoing symptoms of trauma-related distress. This coexistence underscores the importance of addressing both symptom management and growth facilitation in comprehensive care.

Recent research examines factors moderating the relationship between PTG and long-term outcomes. Findings suggest that the authenticity of reported growth matters—growth grounded in genuine cognitive restructuring rather than defensive illusions predicts better long-term adjustment. Additionally, the degree to which individuals actively implement insights gained through their traumatic experience influences outcomes. Growth that remains abstract provides fewer benefits than growth manifesting in behavioural change.

Cultural factors also mediate long-term outcomes. Cross-cultural studies reveal that the expression and implications of post-traumatic growth vary across societies. In individualist Western cultures, growth often emphasises personal strength and autonomy, whilst collectivist cultures may emphasise relational growth and communal contribution. These cultural variations necessitate culturally responsive approaches to PTG research and practice.

Embracing Complexity in Trauma and Transformation

The scientific understanding of post-traumatic growth challenges binary thinking about trauma outcomes. Rather than a simple dichotomy between those who “recover” and those who don’t, research reveals a spectrum of responses characterised by tremendous individual variability. Some individuals experience predominantly distress, others primarily growth, and many navigate both simultaneously throughout their healing journey.

This complexity carries profound implications for how professionals, communities, and individuals themselves approach trauma’s aftermath. Recognising that positive transformation can emerge from struggle does not minimise suffering’s reality or suggest that trauma is somehow beneficial. Rather, it acknowledges human beings’ remarkable capacity for adaptation and meaning-making even in the face of profound adversity.

For Australia’s healthcare landscape, integrating post-traumatic growth principles represents an opportunity to enhance trauma care beyond traditional models focused solely on symptom reduction. By creating environments that facilitate both healing and growth—through compassionate professional support, peer connection, and evidence-based interventions—practitioners can support individuals in navigating trauma’s aftermath in ways that honour both their suffering and their potential for transformation.

The ongoing evolution of resilience research continues revealing new insights into the biological, psychological, and social factors that facilitate human flourishing following adversity. As this understanding deepens, so too does the capacity to support individuals in finding meaning, purpose, and renewed vitality in the wake of life’s most challenging experiences.

Can someone experience post-traumatic growth without professional help?

Whilst professional support can significantly facilitate post-traumatic growth, many individuals experience meaningful transformation through personal reflection, supportive relationships, and engagement with their communities. Research indicates that access to empathetic listeners who validate experiences and provide opportunities for discussing one’s trauma journey plays a crucial role in growth, regardless of whether these individuals are professionals or trusted friends and family members. However, professional guidance particularly benefits those experiencing concurrent trauma-related distress that interferes with daily functioning.

How long after a traumatic event does post-traumatic growth typically emerge?

Post-traumatic growth generally unfolds gradually over months to years following trauma rather than appearing immediately. Research suggests that an initial period of distress and survival typically precedes growth, with many individuals reporting noticeable positive changes between six months and two years post-trauma. However, trajectories vary considerably—some individuals experience early indications of growth, whilst others require longer periods of processing and integration. The temporal course depends on trauma type, individual factors, available support, and engagement in deliberate reflection about the experience.

Does post-traumatic growth mean the trauma wasn’t actually that severe?

Absolutely not. Post-traumatic growth can occur following profoundly severe traumas, and its presence does not diminish the seriousness of the traumatic event or the legitimacy of ongoing distress. Research demonstrates that growth and suffering frequently coexist—individuals can experience both genuine psychological transformation and continued trauma-related symptoms. The misconception that growth indicates a trauma ‘wasn’t that bad’ can be harmful, potentially invalidating survivors’ experiences or creating pressure to demonstrate growth as proof of recovery. Severity and growth potential are separate dimensions.

Are certain types of trauma more likely to lead to post-traumatic growth than others?

Research reveals that post-traumatic growth can follow various trauma types, though characteristics of specific events may influence growth patterns. Traumas that fundamentally challenge core beliefs and assumptions—such as life-threatening illnesses, sudden losses, or events that disrupt one’s sense of safety—may create particular opportunities for profound existential re-evaluation. However, individual and contextual factors often prove more predictive than trauma type alone. The meaning an individual ascribes to their experience and the support available during recovery typically matter more than the specific nature of the traumatic event.

Can focusing on post-traumatic growth invalidate someone’s ongoing struggles with trauma?

This represents a legitimate concern that researchers and clinicians take seriously. Discussing post-traumatic growth requires considerable sensitivity to avoid minimising suffering, creating expectations of growth, or implying that individuals should ‘look on the bright side.’ Ethical practice involves acknowledging growth as one possible outcome whilst validating ongoing distress and recognising that not everyone will experience or desire growth. The goal is expanding possibilities rather than prescribing specific outcomes. Professionals should introduce PTG concepts only when appropriate to an individual’s current state and always in ways that honour their unique experience.