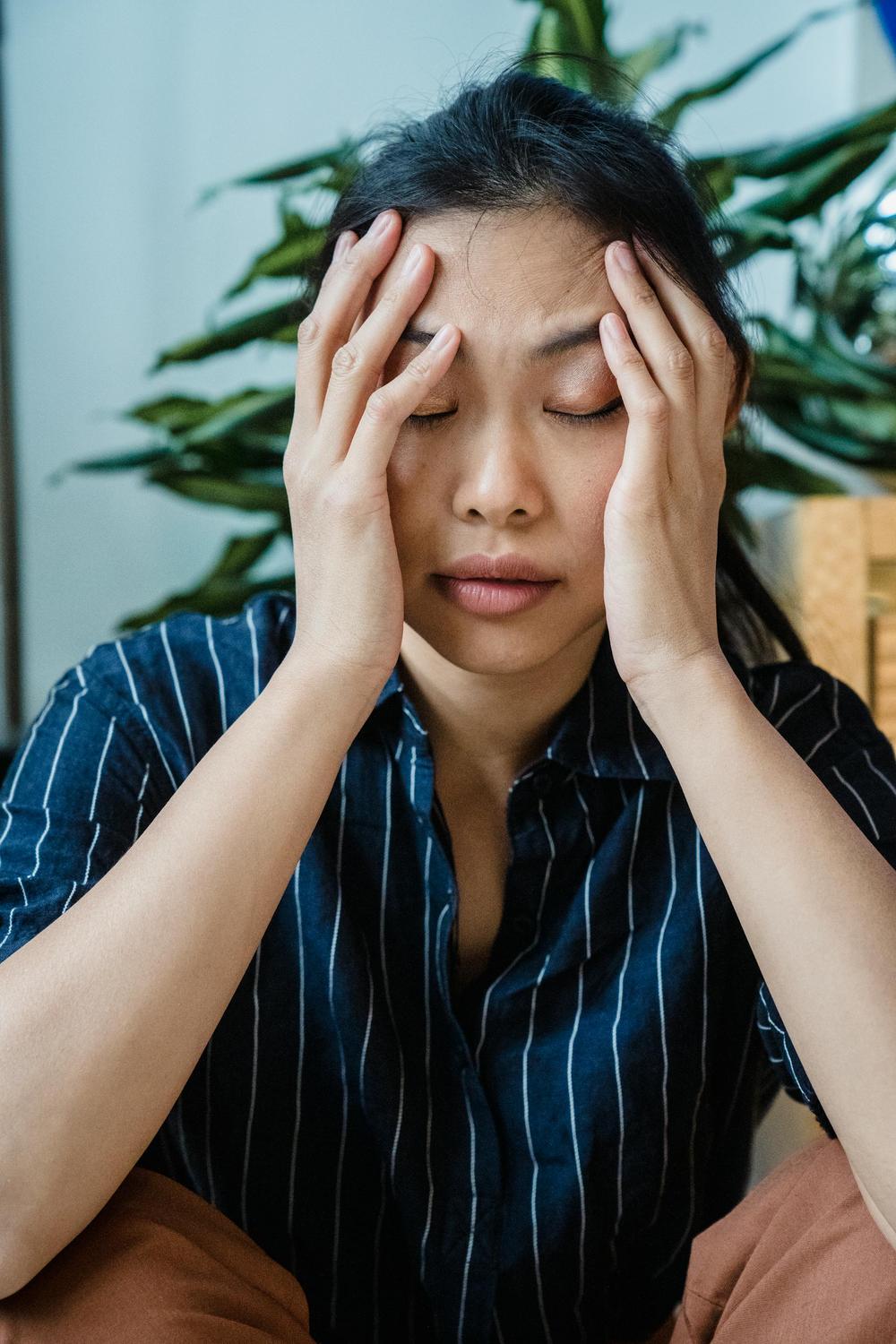

The numbers paint a stark picture: 61% of Australian workers report experiencing burnout—significantly higher than the 48% global average. With workplace exhaustion costing the Australian economy AUD$14 billion annually, and nearly half of employees aged 18-54 feeling drained at work’s end, the search for effective, accessible mental health interventions has never been more urgent. Whilst traditional approaches require substantial time commitments and financial investment, emerging research suggests a deceptively simple ten-minute daily practice may offer profound benefits for psychological wellbeing and resilience.

What Is the Three Good Things Exercise and How Does It Differ from Gratitude Journalling?

The Three Good Things exercise represents one of positive psychology’s most rigorously validated interventions, developed by Dr Martin Seligman and colleagues at the University of Pennsylvania Positive Psychology Center. First empirically tested in 2005, this practice requires participants to write down three positive events from their day each evening, accompanied by explanatory reflections on why each event occurred.

The critical distinction lies in its emphasis on personal agency. Unlike simple gratitude journalling—which passively acknowledges pleasant experiences—the Three Good Things exercise demands active recognition of one’s role in creating positive outcomes. A beautiful sunrise cannot qualify as an entry; however, arranging to watch that sunrise with a friend demonstrates the intentional action that defines this intervention.

This requirement for identifying personal contribution transforms the exercise from passive appreciation into an empowerment tool. Participants must answer: “Why did this happen?” and specifically, “What was my role in making this happen?” This cognitive process reinforces the recognition that individuals actively direct their lives rather than merely experiencing events as passive observers.

The neurobiological rationale stems from the brain’s inherent negativity bias—an evolutionary mechanism prioritising threat detection for survival. Whilst this served ancestral humans well, modern brains remain hardwired to notice and remember negative events disproportionately. The Three Good Things exercise deliberately counteracts this bias through systematic attention retraining, leveraging neuroplasticity to rewire default scanning patterns toward positive stimuli.

How Does the Three Good Things Exercise Work on a Neurological Level?

The brain’s reward system, specifically the mesocorticolimbic circuit, governs incentive salience, associative learning, and positively-valenced emotions. When positive experiences occur, dopamine releases from the ventral tegmental area to the nucleus accumbens, creating pleasure sensations and motivation signals that reinforce behaviour repetition.

The Three Good Things exercise hijacks this natural reward pathway through conscious reflection. Writing about positive events’ causes engages deeper hippocampal processing, strengthening memory encoding. The prefrontal cortex activates during reflection on personal contribution, facilitating cognitive reappraisal and emotional regulation of limbic system responses.

Repeated practice generates neuroplastic changes—the brain gradually rewires its automatic attention patterns. Rather than defaulting to threat surveillance, neural networks begin scanning for and prioritising positive information. This shift isn’t merely psychological; it represents measurable structural and functional brain changes that persist with continued practice.

The evening timing recommendation enhances effectiveness through sleep-dependent memory consolidation. Positive memories recorded before sleep undergo processing during REM cycles, deepening their integration into long-term memory networks and optimising both psychological benefit and sleep quality itself.

What Does Research Evidence Reveal About the Three Good Things Exercise Effectiveness?

The landmark 2005 study published in American Psychologist demonstrated remarkable durability. Participants completing the Three Good Things exercise daily for one week showed increased happiness at one-month follow-up that persisted through three-month and six-month assessments. Those who continued the practice beyond the initial week maintained benefits throughout the study period.

Subsequent replication studies have confirmed these findings across diverse populations. Healthcare workers—a group facing extraordinary stress levels—have shown particularly compelling results. Duke Medical Center research with neonatal intensive care staff demonstrated increased happiness and decreased burnout. Internal medicine residents exhibited lower burnout rates, fewer depressive symptoms, greater happiness, improved work-life balance, reduced colleague conflicts, and enhanced sleep quality.

A 15-day web-based intervention involving 228 healthcare workers, published in BMJ Open (2019), revealed substantial clinical benefits. Emotional exhaustion rates—affecting 50% of participants at baseline—significantly decreased across one-month, six-month, and 12-month follow-ups. Depression symptom prevalence approximately halved, dropping from 37.2% at baseline to 19.1% at one-month follow-up.

The effect sizes merit particular attention. Participants with concerning baseline wellbeing levels exhibited effect sizes ranging from 0.55 to 1.57—demonstrating substantial clinical benefit despite dramatically lower time investment. These findings position the Three Good Things exercise as a clinically meaningful intervention with practical feasibility.

Australian workplace data contextualises these results powerfully. The Corporate Mental Health Alliance Australia’s 2023 survey of 7,995 employees found 44% experiencing some burnout level, with 6% completely burnt out and 11% suffering persistent burnout interfering with work capacity. Healthcare workers face even starker statistics, with Mental Health Australia’s 2022 survey revealing 84% experiencing burnout—a persistently high rate despite increased awareness.

What Implementation Approach Maximises the Three Good Things Exercise Benefits?

The original protocol specifies ten minutes daily for minimum seven consecutive days, though research reveals nuances regarding optimal frequency. Counterintuitively, a study by Lyubomirsky and colleagues found participants practising once weekly showed greater wellbeing improvements than those practising three times weekly—who actually experienced decreased wellbeing. This “frequency paradox” suggests excessive practice may reduce effectiveness by eliminating novelty and diminishing meaningfulness.

The reflection component constitutes the exercise’s active ingredient. For each positive event, participants must document:

- Personal agency identification: What specific role did you play in creating or facilitating this positive outcome?

- Causal attribution analysis: What circumstances, decisions, or actions led to this event occurring?

- Future replication consideration: How might you intentionally create similar positive experiences?

This structured reflection transforms simple event recording into cognitive reappraisal training. The prefrontal cortex engages in evaluating personal contribution, strengthening sense of control and self-efficacy. Recognising one’s capacity to generate positive outcomes creates a powerful psychological feedback loop—increased confidence motivates further positive action, which generates additional positive events to recognise.

Physical writing appears more effective than digital recording, though digital platforms with reminder functions improve adherence. The key requirement involves maintaining an external record—mental noting lacks the memory consolidation benefits and prevents reviewing previous entries to reinforce positive patterns.

Specificity matters considerably. Each day demands three new positive events; repetition diminishes cognitive engagement. Events can range from small everyday occurrences—a pleasant conversation with a colleague, successfully completing a challenging task, enjoying a particularly good meal—to significant milestones. The magnitude matters less than the consistent practice of noticing and attributing.

Who Benefits Most from the Three Good Things Exercise and What Outcomes Can Be Expected?

Meta-analytical evidence demonstrates positive psychology interventions generally show greater effectiveness for individuals already experiencing depressive symptoms compared to non-depressed populations. The Three Good Things exercise follows this pattern, with participants exhibiting concerning baseline wellbeing levels showing larger effect sizes than the overall sample.

Participants have reported increased motivation for positive action, reduced self-criticism, enhanced resilience when facing challenges, and improved social connections as they recognise positive interpersonal interactions more readily. The exercise cultivates a solution-focused approach, shifting thought patterns from defeatist rumination toward constructive problem-solving.

Importantly, the Three Good Things exercise addresses a fundamental limitation of traditional symptom-focused interventions. Research comparing cognitive behavioural therapy with positive psychology components revealed that whilst negative symptoms decreased during CBT phases, positive affect only improved following positive psychology introduction. This finding underscores the necessity of not merely reducing distress but actively building wellbeing—two complementary yet distinct therapeutic goals.

Why Does the Australian Context Make the Three Good Things Exercise Particularly Relevant?

Australian workplace mental health data reveals concerning trends demanding accessible interventions. The TELUS Mental Health Index (2024) indicates 47% of Australian workers feel mentally or physically exhausted at working day’s end, with excessive workload cited as the leading burnout cause by 27% of employees. The national mental health score of 62.5 falls within the “strain range” (50-79), substantially below the optimal threshold (80-100).

Safe Work Australia data compounds these concerns. Mental health conditions now account for 9% of serious workers’ compensation claims—representing a 36.9% increase since 2017-18. The median time lost for mental health conditions exceeds four times that of physical injuries, whilst median compensation surpasses physical injury claims threefold. Workers with mental health claims experience markedly poorer return-to-work outcomes and face persistent stigma.

The economic burden extends beyond individual suffering. Stress-related absenteeism costs Australian businesses billions annually, with burnt-out employees 63% more likely to take sick days and 2.6 times more likely to seek alternative employment. Burnout attribution reaches 40% of employee resignations, creating substantial recruitment and training costs alongside productivity losses.

Despite these challenges, 36% of employees report their organisation isn’t implementing burnout prevention measures, whilst 56% indicate human resources departments don’t encourage burnout conversations. This implementation gap creates an opportunity for evidence-based, low-cost interventions like the Three Good Things exercise.

The intervention’s cost-effectiveness proves particularly compelling for resource-constrained organisations. Requiring only paper and pen (or simple digital platforms), the exercise demands no specialised training, equipment, or ongoing costs. The ten-minute daily commitment minimises disruption to productivity whilst generating returns through reduced absenteeism, improved morale, and enhanced workplace relationships.

International research demonstrates cross-cultural applicability, with positive outcomes documented across Chinese, Indian, Israeli, and Kenyan populations. This cultural adaptability suggests strong potential for Australia’s multicultural workforce, though culturally sensitive implementation remains important for maximising engagement.

How Can Organisations and Individuals Implement the Three Good Things Exercise Effectively?

Successful implementation requires a clear understanding that the Three Good Things exercise differs fundamentally from passive gratitude journalling. Initial orientation should emphasise the active agency component—participants must identify their role in creating positive outcomes, not merely acknowledge pleasant experiences that happened to them.

For individual practice, establishing a consistent routine optimises adherence. Evening practice within two hours of sleep provides dual benefits: stress reduction facilitating sleep onset and memory consolidation during REM cycles. However, morning practice remains acceptable if it increases consistency for specific individuals.

Workplace programmes benefit from organisational support without mandating participation. Voluntary participation with gentle encouragement yields better outcomes than compulsory requirements, which may generate resentment and undermine intrinsic motivation. Providing brief workshops explaining the neurobiological rationale and proper technique increases buy-in and correct implementation.

Digital platforms with reminder functions can enhance adherence, particularly for remote workers. Text message prompts three times weekly demonstrated effectiveness in healthcare worker studies, suggesting less-frequent reminders maintain engagement without creating burden. However, organisations should offer paper-based alternatives for employees preferring tactile journalling experiences.

Group sharing—when voluntary and conducted sensitively—can amplify benefits through vicarious positive experiences and social connection strengthening. Individuals should never feel pressured to disclose personal reflections publicly. Optional sharing with accountability partners or small trusted groups provides a middle-ground between isolated practice and organisation-wide disclosure.

Critical implementation considerations include managing expectations regarding timeline and magnitude of effects. Whilst some participants experience rapid mood improvements, others require several weeks of consistent practice before noticing benefits. Emphasising the neuroplasticity process—gradual brain rewiring rather than immediate transformation—helps sustain motivation through the initial adjustment period.

Organisations should also recognise that whilst the Three Good Things exercise offers substantial benefits, it cannot substitute comprehensive mental health support for individuals experiencing severe psychological distress. The exercise works best as part of broader wellbeing initiatives including access to professional support, reasonable workloads, and psychologically safe workplace cultures.

Integrating the Three Good Things Exercise Within Holistic Wellness Approaches

The Three Good Things exercise complements other evidence-based wellness practices without contraindications. Its compatibility with mindfulness meditation, regular physical activity, adequate sleep hygiene, and social connection initiatives makes it valuable within comprehensive wellbeing programmes addressing whole-person health.

The intervention aligns particularly well with preventative mental health approaches. Rather than waiting for burnout or depression to develop before implementing support, regular Three Good Things practice builds psychological resilience proactively. This resilience enhancement proves especially valuable during high-stress periods, providing cognitive and emotional resources for navigating challenges.

For individuals receiving professional mental health support, the exercise serves as an excellent adjunctive practice. Its structured simplicity allows easy integration with existing routines, whilst the evidence base provides confidence in its safety and efficacy. The focus on building positive experiences and recognising personal agency directly counters common cognitive distortions associated with depression and anxiety.

Organisational wellness initiatives incorporating the Three Good Things exercise alongside other evidence-based practices create synergistic effects. Employees practising multiple wellness behaviours simultaneously often report greater overall benefit than isolated intervention implementation. The exercise’s minimal time commitment makes it ideal for workplace wellness programmes where competing demands limit employee participation in lengthy initiatives.

Understanding Limitations and Setting Realistic Expectations

Whilst research demonstrates substantial benefits, the Three Good Things exercise shows variable individual responses. Some participants experience dramatic improvements in mood and resilience, whilst others notice more modest changes. This variability reflects the complex interplay of genetics, life circumstances, baseline mental health, and individual differences in cognitive processing.

The intervention appears less effective for individuals with very severe depression or active suicidal ideation, who require immediate professional intervention. Similarly, the exercise cannot address structural workplace issues such as chronically excessive workloads, toxic management practices, or systemic inequities. These situations demand organisational-level changes alongside individual coping strategies.

The frequency paradox—where excessive practice reduces effectiveness—warrants careful attention. Organisations implementing programmes should resist the temptation to maximise frequency, instead respecting research indicating once-weekly practice may prove optimal for sustained benefits. The goal involves cultivating a sustainable practice that maintains novelty and meaningfulness rather than creating another burdensome obligation.

Long-term maintenance requires continued practice. Benefits can diminish if the exercise discontinues entirely, though occasional practice appears sufficient for maintaining improvements once initial neuroplastic changes establish. Finding the right balance between consistency and flexibility represents an individual determination based on personal response and circumstances.

Moving Forward with Evidence-Based Psychological Wellbeing

The Three Good Things exercise represents a rare convergence: robust scientific evidence, practical accessibility, cultural adaptability, and cost-effectiveness. In Australia’s current context—characterised by high burnout rates, increasing mental health claims, and substantial economic costs of workplace stress—scalable, evidence-based interventions deserve serious consideration.

The intervention’s strength lies not in replacing comprehensive mental health support but in complementing existing services whilst reaching individuals who might not otherwise access assistance. Its simplicity belies sophisticated neurobiological mechanisms targeting the brain’s fundamental negativity bias through systematic attention retraining and neuroplastic rewiring.

For organisations, the Three Good Things exercise offers a low-risk, high-potential addition to workplace wellbeing programmes. For individuals, it provides an evidence-based tool for building resilience, enhancing mood, and cultivating the capacity to recognise and create positive experiences amidst life’s inevitable challenges.

The practice requires no special equipment, training, or circumstances—merely ten minutes daily, writing materials, and a willingness to consistently notice what went well and acknowledge one’s role in making it happen. This accessibility democratises psychological wellbeing support, extending evidence-based intervention beyond clinical settings into everyday life where sustained practice generates lasting benefit.

As Australian workplaces and healthcare systems grapple with escalating mental health challenges, the Three Good Things exercise stands as a validated, practical tool worthy of broader implementation. Its evidence base continues expanding, its mechanisms grow increasingly understood, and its potential for meaningful impact on both individual and population wellbeing remains substantial.