When 91.5% of large-scale projects exceed their schedule or budget—and only 1% complete perfectly on time and within financial constraints—the question isn’t whether your organisation will face project challenges, but rather how prepared you are to prevent catastrophic failure. In Australian healthcare organisations and complex enterprises, where project failures can cascade into safety incidents, regulatory breaches, and financial losses exceeding millions of dollars, traditional linear approaches to risk management have proven dangerously inadequate. The Swiss Cheese Method offers a fundamentally different paradigm: one that acknowledges multiple defensive layers must work in concert, recognising that no single safeguard can prevent disaster when organisational, supervisory, and operational vulnerabilities align.

The stakes couldn’t be higher. Research demonstrates that over 210,000 deaths annually in the United States alone are linked to preventable errors stemming from mismanaged projects and communication breakdowns—a sobering reminder that project management in healthcare and complex environments transcends mere business concerns. When 70% of hospital strategic initiatives fail, and 52% of projects experience uncontrolled scope creep, organisations need a robust framework that addresses not just surface-level symptoms but the latent failures embedded within organisational structures, decision-making processes, and cultural dynamics.

What Is the Swiss Cheese Method and Why Does It Matter for Large Projects?

The Swiss Cheese Method, formally known as the Swiss Cheese Model, represents a revolutionary approach to understanding how failures occur in complex systems. Developed by Professor James T. Reason at the University of Manchester and first formally propounded in 1990, this framework emerged from analysing catastrophic failures in aviation and healthcare where single-point explanations proved insufficient.

The model employs a powerful visual metaphor: multiple slices of Swiss cheese stacked side-by-side, each representing a defensive layer or line of defence in a system. The holes in each slice represent vulnerabilities, weaknesses, or gaps in that specific defence. Critically, these holes are not static—they dynamically open and close throughout operational cycles, creating what engineers term “resilience.” A single failure in one defensive layer does not cause system failure. However, when holes align across multiple layers simultaneously, they create what Reason termed a “trajectory of accident opportunity,” allowing hazards to pass through all defences and manifest as failure.

The fundamental insight revolutionising project management: accidents and failures rarely result from a single cause but rather from multiple defensive layers failing simultaneously. This understanding shifts the focus from blaming individuals to examining systemic vulnerabilities.

The Swiss Cheese Method distinguishes between two failure types that must be understood for effective project management:

- Active failures occur at the frontline—the unsafe acts by people in direct contact with work processes. These include slips, lapses, mistakes, and violations. Active failures have immediate, visible consequences and open and close frequently throughout the day as people make errors, catch them, and correct them.

- Latent failures are harder to detect—hidden within system or organisational design. These can remain dormant for days, weeks, or months before being triggered. Occurring at higher organisational levels, latent failures include poor organisational culture, inadequate equipment or training, short staffing, unclear policies, and conflicting goals.

For large projects, this distinction proves transformative. A discovery of budget overruns may initially point to estimation errors (active failures) but, through the Swiss Cheese Method, prompt deeper investigation into latent failures such as inadequate training or insufficient resource allocation.

How Does the Swiss Cheese Model Explain Project Failures?

The Swiss Cheese Method reveals that project failures follow predictable patterns when examined through its four organisational levels, each representing a defensive layer with distinct vulnerabilities.

- Organisational influences encompass resource management issues, organisational climate, and operational processes. Inadequate executive leadership can create holes that subsequent layers cannot compensate for.

- Supervisory factors include supervision adequacy and operational planning. Projects lacking experienced project managers suffer when risks go unidentified and scope boundaries erode unchecked.

- Preconditions for unsafe acts involve environmental, individual, and team factors. In healthcare, misaligned expectations and communication gaps can enable frontline errors.

- Unsafe acts occur at the frontline—direct errors or violations by individuals. Investigation using the Swiss Cheese framework often reveals systemic issues at earlier layers.

The Dynamic Nature of Project Vulnerabilities

A critical insight from applying the Swiss Cheese Method is that holes in defensive layers are dynamic. Active failures at the frontline open and close frequently, while latent failures persist and may only be detected after contributing to a larger failure scenario. Continuous monitoring is essential in adapting to changes over project lifecycles.

What Are the Key Defensive Layers in Successful Project Management?

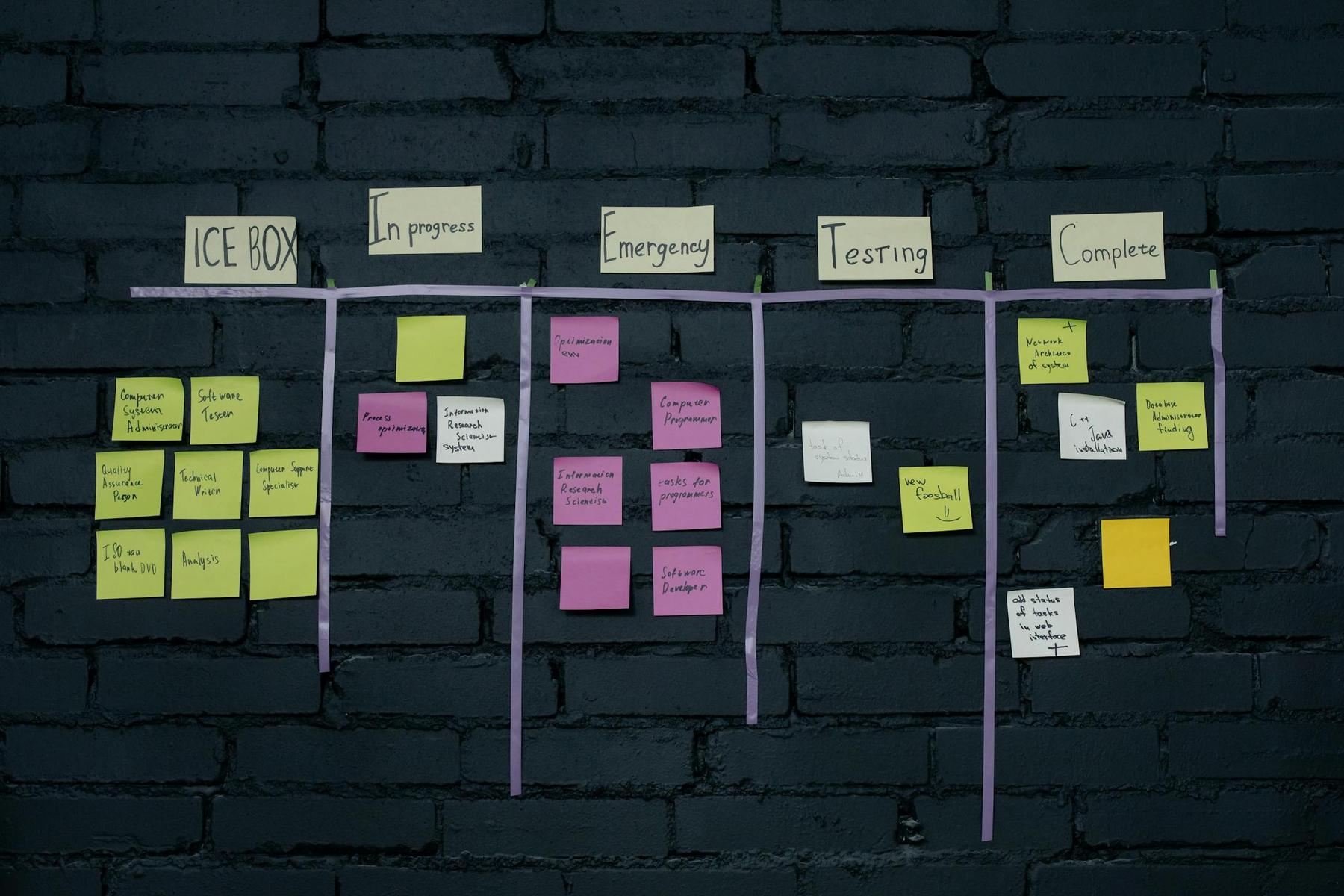

Translating the Swiss Cheese Method into practical project management requires establishing multiple defensive layers:

Layer 1: Executive and Organisational Defence

This foundational layer begins with committed executive sponsorship. Adequate resource allocation, strategic alignment, and a culture of psychological safety form critical defences. Organisations with strong Project Management Offices (PMOs) standardise governance and oversee systemic issues effectively.

Layer 2: Planning and Governance Defence

Comprehensive project planning, unambiguous scope definitions, and formal Change Control Boards (CCBs) prevent the creeping vulnerabilities that lead to scope expansion. Detailed risk registers must capture vulnerabilities across all organisational levels.

Layer 3: Stakeholder Engagement Defence

Engaging cross-functional teams and clarifying roles through tools like RACI matrices helps to manage communication gaps and misaligned expectations. Continuous training reinforces this defence throughout project execution.

Layer 4: Implementation and Execution Defence

Experienced project managers deploy tactical defences through real-time monitoring and continuous risk assessments. Root Cause Analysis (RCA) delves beyond immediate errors to uncover systemic latent failures, steering organisations away from reactive fixes that address only symptoms.

The integration principle: These layers must overlap to compensate for each other’s vulnerabilities. For instance, strong executive sponsorship (Layer 1) can help offset weaknesses in planning or stakeholder engagement if designed to interact cohesively.

How Can Organisations Implement the Swiss Cheese Method for Project Success?

Implementing the Swiss Cheese Method moves beyond theory to practicality, as outlined in the “Knowing, Applying, Ensuring” framework.

The Knowing Phase: Building Foundational Knowledge

Organisations must systematically capture and share lessons from past projects. Establishing repositories of institutional knowledge discourages reliance on individual memory and promotes organisational learning.

The Applying Phase: Operationalising Safeguards

Here, documented knowledge is transformed into actionable processes. Clear role definitions, explicit documentation of decisions, and enhanced attention at risk-prone interfaces form core strategies to prevent failures.

The Ensuring Phase: Sustaining Protective Systems

Ongoing monitoring, regular audits, and feedback loops, combined with a culture of psychological safety, ensure vulnerabilities are promptly identified and addressed. Continuous improvement is key to mitigating latent failures.

Individual-Level Implementation Checklist

At the personal level, self-assessment questions such as whether one is adequately trained or if assumptions have been validated contribute to the frontline defensive layer, reinforcing systemic strength.

Avoiding System Fixes Versus Local Fixes

Local fixes may address individual errors but do not resolve systemic issues. True improvement requires system-wide interventions that address organisational culture, communication, training adequacy, and resource allocation.

What Makes Healthcare and Complex Projects Particularly Vulnerable?

Healthcare projects represent a confluence of challenges:

- Stakeholder Complexity and Competing Priorities: Diverse stakeholder groups often lead to miscommunication and unaligned expectations.

- Continuous Operations and Safety-Critical Context: Continuous service delivery complicates transition phases and amplifies the impact of failures.

- Regulatory Complexity and Evolution: Evolving standards necessitate adaptive governance to avoid latent vulnerabilities.

- Knowledge Dissemination Challenges: Barriers to sharing lessons learned perpetuate systemic vulnerabilities across organisations.

The consistent failure patterns in healthcare projects, with high rates of overruns and unmet targets, underline the necessity of robust, multi-layered defences.

Building Resilient Systems Through Systemic Thinking

The enduring value of the Swiss Cheese Method lies in its systemic perspective. Rather than relying on single-line defences, it promotes multiple, overlapping layers that protect against catastrophic failures.

By addressing both active and latent failures, and by ensuring that defensive layers interact effectively, organisations can transform project management. The focus shifts from assigning blame for frontline errors to examining broader organisational and supervisory vulnerabilities.

As organisations face increasing complexity and stakes rise, the Swiss Cheese Method provides a critical framework for navigating inherent uncertainties. The key is not avoiding vulnerabilities altogether, but ensuring that no single failure can compromise the entire system.