The invisible architecture of your body’s stress response operates with remarkable precision, orchestrating a cascade of hormonal signals that touch every system, every cell, every moment of your physiological existence. When stress strikes—whether from a looming deadline, a relationship challenge, or the constant hum of modern life—your endocrine system launches into action with the sophistication of a finely tuned orchestra. Yet for all its evolutionary brilliance, this ancient survival mechanism faces unprecedented challenges in our contemporary world, where psychological stressors persist far longer than the physical threats our ancestors confronted. Understanding the intricate hormonal cascades triggered by stress isn’t merely academic curiosity; it’s essential knowledge for comprehending how temporary pressures can evolve into chronic health concerns that ripple through cardiovascular, metabolic, immune, and neurological systems.

What Is the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis and Why Does It Matter?

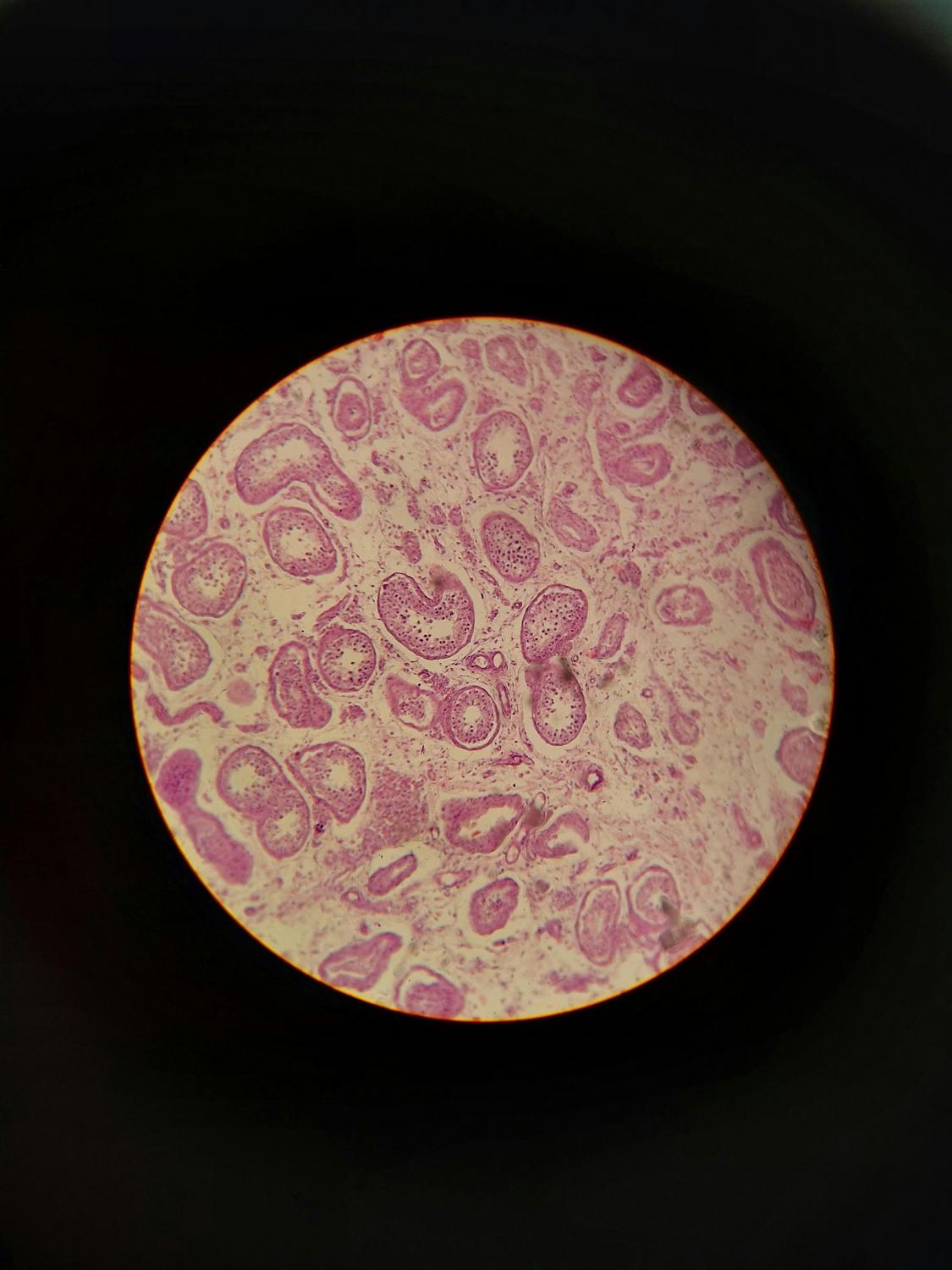

The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis represents the primary neuroendocrine system responsible for orchestrating the body’s stress response. This complex regulatory pathway involves three interconnected components: the hypothalamus (a neuroendocrine structure positioned just above the brainstem), the pituitary gland (often termed the “master gland” due to its central regulatory role), and the adrenal glands (small, conical organs perched atop the kidneys).

The HPA axis functions as more than a simple stress responder. It maintains homeostasis by regulating multiple body processes including digestion, immune responses, mood, emotional states, sexual activity, and energy storage and expenditure. When functioning optimally, this system enables appropriate responses to acute stressors whilst preventing excessive activation that could damage tissues and organs.

Stress itself is defined as a state of real or perceived threat to homeostasis that demands an adaptive response from the organism. The brilliance of the HPA axis lies in its ability to distinguish between different stressor types—whether physical threats like temperature extremes and infections, or psychogenic stressors including emotional and psychological challenges. Critically, the system responds similarly to both real and imagined threats, explaining why psychological stress produces measurable physiological changes.

The importance of HPA axis function extends beyond stress management. Disruption of this system is implicated in major depressive disorder, anxiety disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder, metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, and numerous other conditions affecting quality of life and longevity. Research from the Cleveland Clinic and numerous peer-reviewed studies consistently demonstrates that proper HPA axis regulation is essential for maintaining both mental and physical health.

How Does the Hormonal Cascade Respond to Stress?

The stress-induced hormonal cascade unfolds through precisely timed phases, each building upon the previous to mobilise the body’s resources for threat response. This multi-step process exemplifies biological coordination at its finest.

Phase One: Detection and Initial Signalling

When the brain perceives a stressor, sensory information travels to the amygdala, the brain’s emotional processing centre. The amygdala rapidly evaluates the threat level and transmits stress signals to the hypothalamus, initiating the cascade. This initial phase occurs within seconds, demonstrating the priority evolution has placed on rapid threat detection.

Phase Two: Hypothalamic Response

The hypothalamus responds by releasing corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) from specialised neurons in the paraventricular nucleus. CRH enters the hypophyseal portal blood vessel system, which directly connects to the anterior pituitary gland. Simultaneously, the hypothalamus releases arginine vasopressin (AVP), which potentiates CRH’s effects. This synergistic action amplifies the stress signal, ensuring adequate downstream response.

Phase Three: Pituitary Activation

CRH and AVP bind to receptors on anterior pituitary corticotroph cells, stimulating synthesis and secretion of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) into the bloodstream. ACTH serves as the direct chemical messenger to the adrenal glands. During acute stress, plasma levels of both CRH and ACTH can increase two to five-fold, demonstrating the system’s dynamic range.

Phase Four: Adrenal Response

ACTH travels through the bloodstream to the adrenal cortex, specifically the zona fasciculata layer. Here, it stimulates synthesis and release of cortisol, the primary glucocorticoid in humans. Cortisol production involves a multi-step biochemical process beginning with cholesterol conversion. Peak cortisol levels typically occur approximately 30 minutes after HPA axis activation, providing sustained support for the stress response.

Parallel Sympathetic Activation

Whilst the HPA axis activates, the sympathetic-adrenal-medullary (SAM) system simultaneously triggers. The sympathetic nervous system directly stimulates the adrenal medulla, causing rapid release of catecholamines—epinephrine (adrenaline) and norepinephrine (noradrenaline). These hormones produce the immediate “fight-or-flight” response: increased heart rate, elevated blood pressure, and enhanced alertness. SAM activation occurs within seconds, whilst HPA axis activation provides more sustained support lasting minutes to hours.

| Feature | SAM System | HPA Axis |

|---|---|---|

| Response Speed | Seconds | Minutes to hours |

| Primary Hormones | Epinephrine, Norepinephrine | CRH, ACTH, Cortisol |

| Duration of Action | Short-term (immediate) | Sustained (prolonged) |

| Primary Functions | Cardiovascular activation, immediate energy mobilisation | Metabolic regulation, immune modulation, sustained energy provision |

| Regulation | Neural (sympathetic nerves) | Hormonal (bloodstream) |

| Feedback Mechanism | Rapid autonomic regulation | Glucocorticoid negative feedback |

What Role Does Cortisol Play in the Body’s Stress Response?

Cortisol stands as the primary stress hormone, yet its functions extend far beyond simple stress management. This steroid hormone, synthesised from cholesterol in the adrenal cortex, orchestrates widespread physiological changes designed to enhance survival during threatening situations.

Biochemical Distribution and Activity

In circulation, cortisol exists in two forms: bound cortisol (90-95% of total) and free cortisol (5-10%). Bound cortisol attaches to cortisol-binding globulin (approximately 80%) and albumin (10-15%), creating an inactive reservoir. Only free cortisol possesses biological activity, capable of entering cells and interacting with receptors to produce physiological effects.

Circadian Rhythm

Cortisol follows a distinct circadian rhythm regulated by the suprachiasmatic nucleus, the body’s master circadian clock. In healthy individuals, cortisol peaks in the early morning (30-45 minutes after waking)—termed the cortisol awakening response—then gradually declines throughout the day, reaching its lowest point around midnight. Additionally, cortisol releases in pulsatile bursts approximately every one to two hours. During acute stress, both the amplitude and synchronisation of these secretory pulses increase, demonstrating the system’s responsiveness.

Metabolic Effects

Cortisol fundamentally alters energy metabolism. It increases blood glucose through gluconeogenesis (glucose synthesis in the liver) and glycogenolysis (breakdown of stored glycogen). Simultaneously, it stimulates lipolysis (fat breakdown) in adipose tissue whilst decreasing glucose uptake in peripheral tissues. These changes ensure sufficient energy availability for the brain and muscles during stress. However, cortisol also inhibits insulin secretion and promotes insulin resistance, explaining why chronic stress increases diabetes risk.

Cardiovascular Effects

Cortisol increases heart rate, cardiac output, and blood pressure through vasoconstriction. It enhances blood flow to muscles and brain whilst potentiating the effects of catecholamines. These cardiovascular changes prepare the body for physical action, whether confronting or fleeing from threats.

Immune and Inflammatory Modulation

Cortisol profoundly influences immune function. It suppresses pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1, TNF-alpha, IFN-gamma) whilst increasing anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-4, IL-10, IL-13). Cortisol induces programmed death of pro-inflammatory T cells, reduces neutrophil migration, and diminishes B cell antibody production. This anti-inflammatory action protects against excessive immune system activation that could damage tissues. However, chronic cortisol elevation can suppress immune surveillance, increasing infection susceptibility.

Reproductive Suppression

Stress-induced cortisol elevation suppresses reproductive function at multiple levels. It inhibits gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), luteinising hormone (LH), and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) release. Cortisol directly suppresses gonadal steroid production (testosterone and oestrogen). These effects can manifest as stress-induced amenorrhea in women, decreased libido, and hypo-fertility in both sexes.

Neurological Effects

Within the central nervous system, cortisol enhances memory consolidation for threatening events whilst increasing arousal, alertness, and focused attention. It induces analgesia (pain relief) and affects mood and emotional regulation through interactions with the limbic system. These neurological effects sharpen cognitive performance during acute stress but become detrimental when chronically elevated.

The Negative Feedback Loop

Cortisol’s most critical function involves terminating its own production through negative feedback. When blood cortisol levels rise sufficiently, receptors in the hypothalamus, anterior pituitary, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex detect the elevation and inhibit further CRH and ACTH secretion. This self-limiting mechanism prevents excessive, prolonged cortisol exposure. Disruption of this feedback loop underlies numerous stress-related pathological conditions.

How Does Chronic Stress Affect the Endocrine System?

Whilst acute stress responses evolved to enhance survival during temporary threats, chronic stress—persisting over weeks, months, or years—produces fundamentally different physiological changes. The endocrine system’s adaptive mechanisms, designed for episodic activation, become maladaptive when continuously engaged.

HPA Axis Adaptation and Maladaptation

Initially, the HPA axis adapts to chronic stress through dynamical compensation. The pituitary corticotrophs and adrenal cortex increase their functional mass to buffer sustained stress demands. This compensatory enlargement temporarily maintains hormone production. However, long-term gland mass enlargement leads to dysregulation. Recovery of gland masses and hormone levels after stress removal can require weeks, explaining prolonged HPA dysfunction following stressor cessation.

Glucocorticoid Resistance

Chronic stress produces glucocorticoid resistance, also termed glucocorticoid insensitivity. Multiple mechanisms contribute: downregulation of glucocorticoid receptor (GR) expression in target cells, reduced GR sensitivity and affinity for cortisol, and impaired glucocorticoid receptor-mediated negative feedback. Despite elevated cortisol concentrations, the negative feedback loop fails to terminate the stress response. This creates a pathological cycle of sustained HPA axis hyperactivation, where elevated cortisol paradoxically fails to suppress further CRH and ACTH release.

Altered Cortisol Patterns

Chronic stress fundamentally disrupts normal cortisol rhythms. The characteristic circadian pattern flattens, with reduced morning peaks and elevated evening levels. The normal pulsatile pattern becomes more continuous. Most significantly, the system’s response to acute stressors becomes either exaggerated (hyperreactivity) or blunted (hypo-reactivity). These alterations associate with burnout, depression, and other psychiatric conditions.

Oxidative Stress Mechanisms

Chronic glucocorticoid elevation increases cellular oxidative stress throughout the body. Cortisol increases metabolic rate, promoting free radical production via the electron transport chain. Reactive oxygen species—including superoxide, hydrogen peroxide, and hydroxyl radicals—accumulate whilst antioxidant enzyme activity (superoxide dismutase, catalase, glutathione peroxidase) decreases. This imbalance produces lipid peroxidation, protein carbonyl formation, and DNA damage, particularly affecting redox-sensitive brain regions including the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex.

Cross-Axis Dysregulation

Chronic HPA axis activation disrupts other endocrine axes. The hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid (HPT) axis experiences suppression, with elevated cortisol inhibiting thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) secretion and reducing T3 and T4 levels. This produces decreased metabolism, fatigue, and mood changes. The hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis faces even more pronounced suppression, with stress directly inhibiting reproductive function at multiple levels, causing amenorrhea, anovulation, and reduced fertility in women, and decreased testosterone, impaired sperm production, and erectile dysfunction in men.

What Are the Systemic Effects of Stress-Related Hormonal Changes?

The hormonal cascades initiated by chronic stress extend beyond the endocrine system, affecting virtually every physiological system. These widespread effects demonstrate the interconnected nature of human physiology.

Cardiovascular System

Acute stress produces beneficial cardiovascular changes: increased heart rate, stronger contractions, and elevated blood pressure. However, chronic stress creates pathological changes. Sustained elevation in blood pressure progresses to hypertension. Vascular endothelial dysfunction develops, promoting atherosclerosis and coronary artery disease. Inflammation in coronary arteries increases alongside unfavourable changes in lipid metabolism (dyslipidaemia). These changes substantially increase heart attack and stroke risk. Research from the American Psychological Association demonstrates that postmenopausal women face particularly elevated cardiovascular risk from chronic stress due to loss of oestrogen’s protective effects.

Immune System Dysfunction

Chronic stress creates a paradoxical immune state characterised by both immunosuppression and inflammation. T-cell activity, B-cell antibody production, and natural killer cell function all decline, increasing infection susceptibility and impairing wound healing. Simultaneously, chronic low-grade inflammation develops, with elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1, IL-6, TNF-alpha). Glucocorticoid resistance impairs cortisol’s anti-inflammatory effects. This combination exacerbates autoimmune and inflammatory conditions including rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, and inflammatory bowel disease.

Metabolic Syndrome

Chronic cortisol elevation promotes central (abdominal) obesity, increases appetite through ghrelin elevation and leptin reduction, and induces insulin resistance and glucose intolerance. Dyslipidaemia develops, characterised by elevated triglycerides and reduced HDL cholesterol. These changes cluster into metabolic syndrome—central obesity, hypertension, glucose intolerance, and dyslipidaemia—substantially increasing type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease risk.

Gastrointestinal Effects

Stress hormones profoundly affect digestive function. Cortisol and catecholamines delay gastric emptying, reduce intestinal motility (potentially causing either constipation or diarrhoea), decrease intestinal blood flow through vasoconstriction, and inhibit digestive secretions. Chronic stress increases intestinal permeability (“leaky gut”) and dysregulates gut microbiota composition. These changes manifest as irritable bowel syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease exacerbation, reflux, and abdominal pain. The bidirectional gut-brain axis means dysbiosis further amplifies stress responses.

Musculoskeletal System

Chronic cortisol elevation causes muscle wasting and weakness through inhibited protein synthesis and increased protein breakdown. Bone density decreases as cortisol inhibits osteoblasts (bone-building cells) whilst activating osteoclasts (bone-resorbing cells), increasing osteoporosis risk. Chronic muscle tension develops, and recovery from musculoskeletal injuries slows. These changes increase fibromyalgia, chronic low back pain, and tension headache risk.

Central Nervous System Changes

The brain demonstrates particular vulnerability to chronic stress. The hippocampus—critical for memory and stress regulation—experiences atrophy and reduced volume. Neurogenesis (generation of new neurons) declines, impairing memory formation and consolidation. Simultaneously, the hippocampus’s ability to inhibit the HPA axis diminishes, creating a positive feedback amplification of stress responses. The prefrontal cortex suffers reduced volume and synaptic density, impairing executive function, impulse control, and emotional regulation. Conversely, the amygdala increases in volume and reactivity, enhancing fear responses and anxiety. Neuroinflammation develops as microglia (brain immune cells) activate, producing pro-inflammatory cytokines within the central nervous system. Neurotransmitter systems undergo profound changes, with altered serotonin and dopamine metabolism, increased noradrenergic tone, and disturbed GABA and glutamate balance, producing mood disturbance, anxiety, and impaired motivation.

How Do Individual Factors Influence Stress Response?

Individual variation in stress responses demonstrates that hormonal cascades don’t operate identically across populations. Multiple factors modulate how individuals experience and respond to stress.

Genetic Influences

Genetic variation substantially affects stress response magnitude. Genes controlling stress responses maintain most people at relatively steady emotional levels, but some individuals possess more or less active stress responses due to genetic variants. Gene-environment interactions prove particularly important: genetic vulnerability combined with environmental stressors substantially increases disease risk. The FKBP5 gene provides a compelling example—its interaction with early life stress predicts adult depression and HPA axis dysfunction.

Sex and Gender Differences

Preclinical research demonstrates that female HPA axes activate more rapidly than males and produce larger hormone output. However, human studies yield inconsistent findings, likely reflecting variation in stressors studied, oral contraceptive use, menstrual cycle stage, and age differences. Age-specific patterns emerge clearly: younger women demonstrate lower cortisol responses to stress than young men, whilst older women show higher cortisol responses than older men. Sex hormones play modulatory roles—progesterone inhibits cortisol response in women, whilst testosterone performs similar functions in men. Oestrogen enhances cortisol negative feedback in premenopausal women, providing partial protection against stress effects.

Early Life Experiences

Early life stress exposure produces profound long-term consequences through altered HPA axis development during critical developmental periods, programming of stress response sensitivity, and epigenetic changes affecting stress-response genes. Interestingly, early mild-to-moderate stress can enhance HPA regulation and promote lifelong resilience, whilst early severe or prolonged stress results in hyperactive HPA axes and increased lifetime vulnerability. Maternal caregiving quality proves particularly important—high-quality maternal care reduces stress reactivity, whilst neglect or abuse increases it.

Coping Strategies and Resilience

Psychological coping styles modulate HPA responses significantly. Proactive coping associates with lower HPA reactivity, whilst reactive or passive coping associates with higher reactivity. Individual resilience factors determine vulnerability versus adaptation to stress. Neural mechanisms of resilience involve engagement of prefrontal cortex-mediated regulation of the amygdala and HPA axis, demonstrating that psychological factors produce measurable neurobiological changes.

Age-Related Changes

Cortisol patterns change across the lifespan. Infancy features highest cortisol levels without circadian variation. Circadian rhythm emerges after age one, with further development through childhood and adolescence. Adulthood brings stable cortisol rhythms. From age 40 onwards, 24-hour urinary free cortisol follows a U-shaped pattern: decreasing in the second and third decades, stabilising through the 40s-50s, then increasing thereafter. Older adults demonstrate higher baseline cortisol throughout the day, increased evening/night cortisol, and advanced peak timing. Simultaneously, DHEA and DHEA-S (protective hormones) decline with ageing, particularly the capacity to secrete them during acute stress. This reduces the beneficial DHEA/cortisol ratio, increasing vulnerability to chronic stress effects and contributing to cognitive impairment, cardiovascular disease, metabolic dysfunction, and increased mortality risk in older populations.

Understanding the Balance: When Stress Responses Become Health Concerns

The hormonal cascades triggered by stress represent evolutionary adaptations that enhance survival during acute threats. The rapid mobilisation of energy, cardiovascular activation, immune modulation, and cognitive sharpening served our ancestors extraordinarily well when facing predators or environmental dangers requiring immediate physical response. These same mechanisms continue benefiting us during truly acute stressors—major accidents, sudden illnesses, or genuine physical threats.

However, modern life presents a fundamental mismatch. The psychological stressors dominating contemporary experience—work pressures, financial concerns, relationship difficulties, information overload—activate identical hormonal cascades designed for brief, physical threats. When these stressors persist chronically, the adaptive stress response transforms into a pathological state. The HPA axis, designed for episodic activation with recovery periods, instead maintains chronic hyperactivation. Glucocorticoid resistance develops, negative feedback fails, and the system becomes trapped in sustained elevation.

Recognition represents the crucial first step. Understanding that fatigue, sleep disturbance, weight gain (particularly abdominal), difficulty concentrating, mood changes, frequent infections, digestive complaints, and cardiovascular symptoms may reflect chronic stress effects rather than isolated conditions enables more comprehensive approaches to wellbeing. The interconnected nature of endocrine, immune, metabolic, cardiovascular, and neurological systems means addressing chronic stress requires holistic consideration rather than symptom-by-symptom management.

Assessment of HPA axis function, when clinically indicated, provides valuable insights. Measurements including salivary cortisol (particularly diurnal patterns and the cortisol awakening response), serum cortisol, and DHEA/DHEA-S ratios can reveal dysregulation patterns. However, interpretation requires expertise, as cortisol levels vary throughout the day, and single measurements often prove insufficient.

For Australians navigating the stresses of contemporary life—whether in Perth’s competitive work environment, the challenges of regional isolation, or the universal pressures of modern existence—recognising stress’s endocrine effects empowers more informed health conversations. Resources including HealthDirect Australia’s 24/7 helpline (1800 022 222) provide accessible starting points for those concerned about stress-related symptoms.

The remarkable complexity of stress-induced hormonal cascades—from initial hypothalamic activation through pituitary signalling, adrenal hormone release, systemic effects, and feedback regulation—demonstrates the body’s sophisticated regulatory mechanisms. Yet this same complexity reveals vulnerability points where chronic activation produces dysfunction cascading through multiple systems. By understanding these mechanisms, individuals and healthcare providers can better recognise when stress transcends normal adaptive responses, requiring comprehensive assessment and intervention.

Looking to discuss your health options? Speak to us and see if you’re eligible today.

What is the difference between acute and chronic stress responses in the endocrine system?

Acute stress responses involve temporary HPA axis activation lasting minutes to hours, producing beneficial adaptations including energy mobilisation, cardiovascular activation, and enhanced cognition, followed by prompt termination via negative feedback. Chronic stress responses involve sustained HPA axis activation over weeks to years, producing glucocorticoid resistance, failed negative feedback, altered cortisol rhythms, cross-axis endocrine dysregulation, and widespread pathological effects across multiple systems. The key distinction lies in duration and the system’s ability to return to baseline homeostasis.

How long does it take for cortisol levels to return to normal after a stressful event?

Following acute stress, cortisol levels typically peak approximately 30 minutes after HPA axis activation, then decline over the subsequent hours as negative feedback mechanisms engage. In healthy individuals with properly functioning HPA axes, cortisol generally returns to baseline within 60-90 minutes after stressor cessation. However, this timeline can vary based on the intensity of the stressor, individual factors, and overall HPA axis health. Chronic stress may disrupt this recovery pattern.

Can stress permanently damage the endocrine system?

While the endocrine system demonstrates remarkable plasticity and recovery capacity, prolonged severe stress can produce lasting changes. Chronic stress can lead to adaptive increases in pituitary and adrenal gland mass, structural changes in brain regions regulating HPA function, glucocorticoid receptor downregulation, and epigenetic changes that increase vulnerability. However, appropriate interventions can often promote significant recovery even after prolonged stress exposure.

Why do some people handle stress better than others?

Individual stress resilience reflects complex interactions between genetics, early life experiences, sex hormones, age, psychological coping strategies, and social support. Genetic variations can influence baseline HPA reactivity, while early life experiences can program stress responses through epigenetic changes. Moreover, proactive coping, cognitive reappraisal, and strong social connections help buffer against excessive stress responses.

What role does DHEA play in stress response, and why is the DHEA/cortisol ratio important?

DHEA, a hormone produced in the adrenal cortex, acts as a counterbalance to cortisol by providing neuroprotection, supporting immune function, and maintaining anabolic processes. The DHEA/cortisol ratio is important because it reflects the balance between catabolic and anabolic processes; a higher ratio suggests better stress resilience, while a lower ratio indicates greater vulnerability to the harmful effects of chronic stress.