In the quiet hours when most Australians should be experiencing restorative sleep, over 1.5 million people lie awake struggling with diagnosed sleep disorders that silently erode their health, productivity, and quality of life. This hidden epidemic costs Australia’s healthcare system over $5.1 billion annually, with an additional $31.4 billion equivalent impact in reduced quality of life—yet many sufferers remain unaware that their restless nights and exhausted days represent treatable medical conditions rather than simply “poor sleep habits.”

Sleep disorders encompass a complex spectrum of conditions that disrupt the natural architecture of sleep, affecting everything from the ability to fall asleep to maintaining restful sleep throughout the night. These conditions extend far beyond occasional sleeplessness, representing serious medical pathologies that can profoundly impact cardiovascular health, cognitive function, emotional regulation, and overall wellbeing. Understanding the various types of sleep disorders, their prevalence, and their interconnected effects on health is crucial for recognising when sleep difficulties warrant professional evaluation and comprehensive management.

What Are the Most Common Types of Sleep Disorders Affecting Australians?

Sleep disorders in Australia follow patterns similar to those observed globally, with certain conditions demonstrating particularly high prevalence rates that reflect both lifestyle factors and improved diagnostic capabilities. The most prevalent sleep disorders affecting Australian adults include obstructive sleep apnea, chronic insomnia, and restless legs syndrome, which collectively account for the majority of diagnosed cases requiring medical intervention.

Obstructive sleep apnea emerges as the most widespread condition, affecting approximately 33.5% of middle-aged adults when clinically significant disease criteria are applied. This figure increases dramatically to 69.6% when any degree of sleep-disordered breathing is considered, reflecting the spectrum nature of this condition. The disorder involves repeated episodes of partial or complete upper airway collapse during sleep, leading to intermittent oxygen deprivation and fragmented sleep that can have serious long-term health consequences.

Chronic insomnia represents the second most prevalent condition, affecting approximately 13.1% of Australian adults using conservative diagnostic criteria. However, the broader impact of insomnia symptoms extends to 30-60% of the population, indicating the widespread nature of sleep initiation and maintenance difficulties. This condition encompasses various subtypes, including adjustment insomnia triggered by specific stressors, psychophysiological insomnia characterised by learned sleep-preventing associations, and idiopathic insomnia that appears to originate in childhood with persistent lifelong patterns.

Restless legs syndrome affects approximately 3.1% of adults with clinically significant symptoms, though prevalence rates increase substantially with age, particularly affecting individuals over 60 years. The condition involves uncomfortable sensations in the legs during periods of rest or inactivity, creating an irresistible urge to move that can severely interfere with sleep initiation and maintenance.

| Sleep Disorder Type | Prevalence in Australian Adults | Primary Characteristics | Peak Age of Onset |

|---|---|---|---|

| Obstructive Sleep Apnea | 33.5% (clinically significant) | Repeated airway collapse, fragmented sleep | 40-60 years |

| Chronic Insomnia | 13.1% (diagnostic criteria) | Difficulty initiating/maintaining sleep | Any age |

| Restless Legs Syndrome | 3.1% (clinically significant) | Uncomfortable leg sensations, urge to move | Over 60 years |

| Narcolepsy | 0.05% (1 in 2,000) | Excessive daytime sleepiness, sleep attacks | Adolescence/young adulthood |

| Sleepwalking | 1.5% (adults), 5.0% (children) | Complex behaviours during sleep | Childhood |

The classification system for sleep disorders organises these conditions into distinct categories based on their underlying mechanisms and clinical presentations. These include insomnia disorders, sleep-related breathing disorders, central disorders of hypersomnolence, parasomnias, sleep-related movement disorders, and circadian rhythm sleep-wake disorders. Each category encompasses multiple specific conditions that require tailored diagnostic and management approaches.

The substantial economic burden of sleep disorders reflects both their high prevalence and their wide-ranging impact on health and functioning. Direct healthcare costs of $270 million annually represent only a fraction of the total burden, with an additional $540 million in healthcare costs for associated conditions and $4.3 billion in indirect costs primarily related to lost productivity and accident-related expenses.

How Do Sleep-Related Breathing Disorders Impact Daily Life?

Sleep-related breathing disorders represent some of the most clinically significant sleep pathologies due to their potential for serious cardiovascular, neurocognitive, and metabolic consequences when left undiagnosed. These conditions range from simple snoring to life-threatening episodes of complete airway obstruction, with obstructive sleep apnea constituting the most prevalent and medically important variant.

The pathophysiology of obstructive sleep apnea involves complex interactions between anatomical factors, neuromuscular control mechanisms, and arousal responses. During sleep, reduced muscle tone in upper airway structures, combined with anatomical narrowing from factors such as enlarged tonsils, increased neck circumference, or craniofacial abnormalities, leads to airway collapse when inspiratory effort generates negative pressure. These obstructive events result in intermittent oxygen deprivation, carbon dioxide retention, and fragmented sleep due to recurrent arousals necessary to restore airway patency and normal breathing.

The clinical consequences of untreated obstructive sleep apnea extend well beyond sleep disruption and daytime fatigue. The condition demonstrates strong associations with hypertension, cardiovascular disease, stroke, diabetes mellitus, and premature mortality. The intermittent oxygen deprivation and sleep fragmentation characteristic of sleep apnea trigger inflammatory processes, oxidative stress, and sympathetic nervous system activation that contribute to these serious comorbid conditions.

Excessive daytime sleepiness resulting from sleep fragmentation creates significant safety concerns, substantially increasing the risk of motor vehicle accidents and occupational injuries. The microsleep episodes that can occur during monotonous activities pose particular dangers for drivers, machinery operators, and individuals in safety-critical occupations. Studies consistently demonstrate 2-7 fold increases in accident rates among individuals with untreated sleep apnea compared to those without the condition.

Central sleep apnea represents a less common but clinically significant variant characterised by a lack of respiratory effort during apneic events. Unlike obstructive sleep apnea, central events occur when the brain temporarily stops sending signals to the muscles responsible for breathing, resulting in cessation of both airflow and respiratory effort. This condition often associates with underlying medical conditions affecting the central nervous system, heart failure, or certain environmental factors.

Sleep hypoventilation disorders involve chronically inadequate ventilation during sleep, leading to sustained elevation of carbon dioxide levels and reduction of oxygen saturation. These conditions can result from various underlying pathologies including obesity hypoventilation syndrome, neuromuscular disorders, chest wall abnormalities, or central nervous system dysfunction. The chronic nature of hypoventilation distinguishes these disorders from the intermittent respiratory events characteristic of sleep apnea.

The impact on cognitive functioning represents another significant consequence of sleep-related breathing disorders. Individuals with untreated sleep apnea frequently experience impaired concentration, memory difficulties, reduced reaction times, and decreased executive functioning that can affect occupational performance, academic achievement, and daily activities. These cognitive effects often improve substantially with appropriate intervention, highlighting the reversible nature of many sleep apnea-related impairments.

Why Are Insomnia and Hypersomnolence Disorders Often Misunderstood?

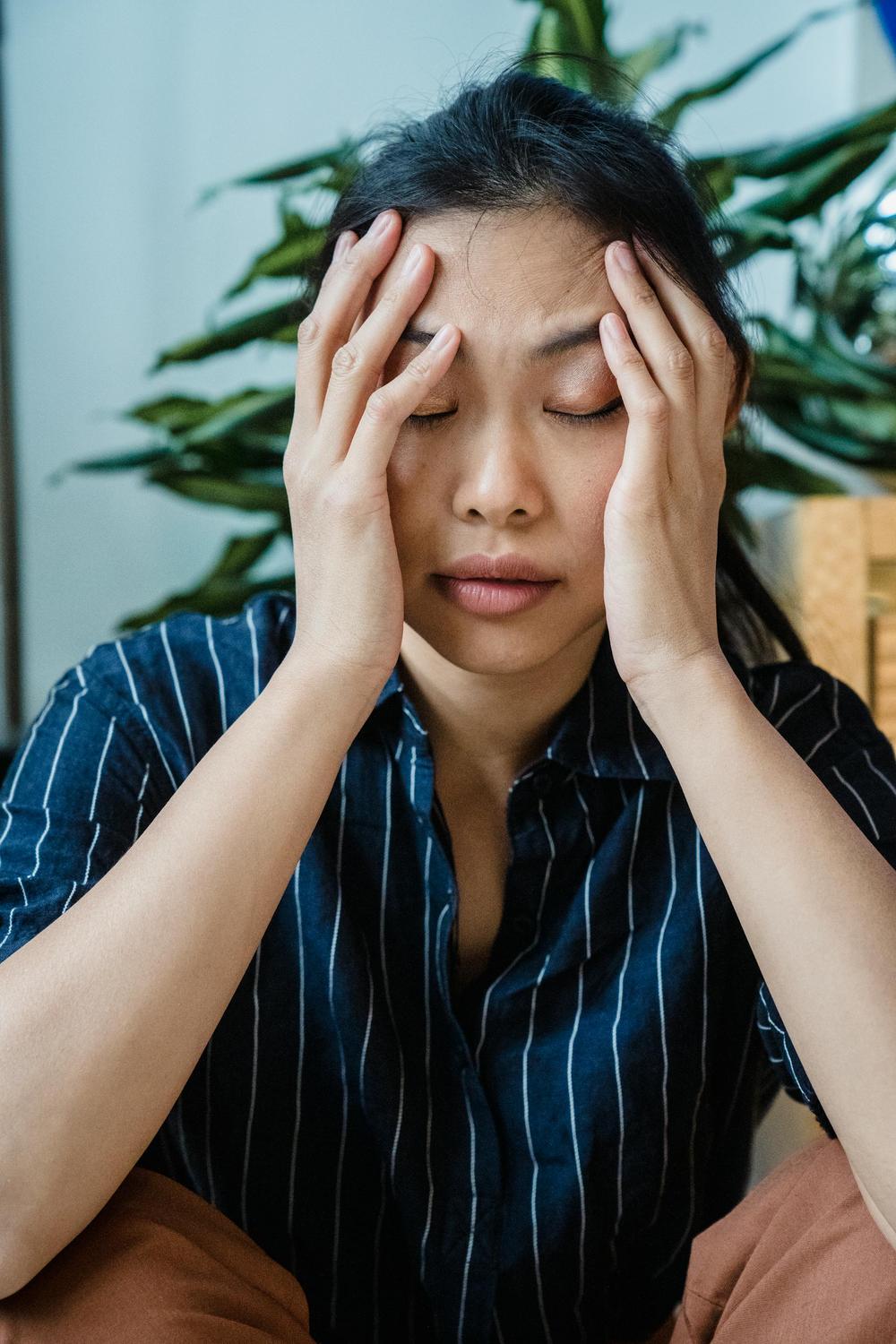

Insomnia disorders represent the most commonly reported sleep complaints globally, yet they remain frequently misunderstood by both patients and healthcare providers due to their complex presentations, varied underlying mechanisms, and the common misconception that sleep difficulties are simply lifestyle issues rather than legitimate medical conditions requiring professional evaluation and evidence-based management approaches.

The complexity of insomnia stems from its heterogeneous nature, encompassing multiple subtypes with distinct clinical features and underlying pathophysiology. Adjustment insomnia represents the most transient form, developing in association with specific psychological, physiological, environmental, or physical stressors and typically resolving within days to weeks once precipitating factors are removed. However, what begins as situational sleep difficulty can evolve into chronic insomnia through learned associations and behavioral patterns that perpetuate sleep disturbance long after initial triggers have resolved.

Psychophysiological insomnia constitutes a more persistent form characterised by heightened arousal levels and learned sleep-preventing associations that create self-perpetuating cycles of sleep anxiety and arousal. Individuals with this condition often develop excessive preoccupation with their inability to sleep, creating anticipatory anxiety around bedtime that further interferes with the relaxation necessary for sleep initiation. The bedroom environment itself can become associated with frustration and wakefulness rather than rest and sleep.

Paradoxical insomnia presents particularly challenging diagnostic considerations, involving complaints of severe insomnia without corresponding objective evidence of sleep disturbance or the degree of daytime impairment typically expected based on reported sleep loss. Patients with this condition often report minimal or no sleep on most nights yet maintain relatively normal daytime functioning, suggesting potential discrepancies between subjective sleep perception and actual sleep architecture.

Central disorders of hypersomnolence encompass conditions characterised by excessive daytime sleepiness that cannot be attributed to disturbed nocturnal sleep, circadian rhythm disorders, or sleep-related breathing disorders. These conditions arise from dysfunction in central nervous system mechanisms that regulate sleep-wake states and can significantly impair daytime functioning, safety, and quality of life.

Narcolepsy represents the most well-characterised central hypersomnolence disorder, involving instability in normal transitions between sleep and wake states. The condition affects approximately 1 in 2,000 individuals and involves a characteristic tetrad of symptoms including excessive daytime sleepiness, cataplexy, hypnagogic or hypnopompic hallucinations, and sleep paralysis. The underlying pathophysiology involves loss of specific neurons in the hypothalamus, resulting in inability to maintain stable wakefulness and leading to intrusion of rapid eye movement sleep phenomena into wakefulness.

Idiopathic hypersomnia presents as another important central hypersomnolence disorder characterised by excessive daytime sleepiness despite adequate or prolonged nocturnal sleep. The condition can involve major sleep episodes of at least 10 hours duration accompanied by persistent daytime sleepiness, yet unlike narcolepsy, typically lacks cataplexy and rapid eye movement sleep abnormalities. Daytime naps are often unrefreshing, and individuals frequently experience difficulty awakening from sleep, requiring multiple loud alarms and often displaying confusion and disorientation upon awakening.

The misunderstanding of these disorders often stems from their invisible nature—unlike conditions with obvious physical symptoms, sleep disorders primarily affect subjective experiences and cognitive functioning that may not be readily apparent to others. This invisibility can lead to minimisation of symptoms by both patients and healthcare providers, delayed diagnosis, and inadequate management approaches that focus on symptom suppression rather than addressing underlying pathophysiology.

What Role Do Parasomnias and Movement Disorders Play in Sleep Health?

Parasomnias represent a diverse group of abnormal behaviours, experiences, or physiological events that occur in association with sleep, specific sleep stages, or sleep-wake transitions. These conditions can manifest as complex behaviours, altered perceptions, or abnormal movements that can be disturbing, dangerous, or disruptive to both affected individuals and their bed partners, significantly impacting sleep quality and safety considerations.

The classification of parasomnias organises these conditions according to the sleep stage from which they arise, creating distinct categories for non-rapid eye movement parasomnias, rapid eye movement-related parasomnias, and other parasomnias that do not clearly align with specific sleep stages. This classification system reflects underlying neurophysiology and helps guide targeted management approaches based on the mechanisms involved in each category.

Non-rapid eye movement parasomnias arise from incomplete dissociation between sleep and wakefulness, typically occurring during deep sleep stages when the capacity for complex motor behaviours persists despite continued sleep. These conditions include confusional arousals, sleepwalking, and sleep terrors, all sharing common features including occurrence during the first third of the night, partial or complete amnesia for events, and resistance to awakening during episodes.

Sleepwalking represents one of the most recognised non-rapid eye movement parasomnias, involving complex locomotor behaviours during sleep ranging from simple sitting up in bed to elaborate sequences of activities such as walking, opening doors, or engaging in routine tasks. Current prevalence rates indicate approximately 5.0% of children and 1.5% of adults experience sleepwalking, with lifetime prevalence reaching approximately 6.9% overall. Most cases begin during childhood and often resolve by adulthood, though adult-onset sleepwalking requires careful evaluation as it may associate with underlying neurological conditions or other factors.

Sleep terrors involve dramatic episodes of intense fear and autonomic arousal during sleep, characterised by sudden awakening with screaming, rapid heart rate, perspiration, and apparent terror that typically cannot be explained or remembered by the individual. These events prove particularly distressing for family members who witness them, as the affected person appears to be in extreme distress but cannot be comforted or fully awakened during episodes.

Rapid eye movement-related parasomnias occur during rapid eye movement sleep and involve different underlying mechanisms than non-rapid eye movement parasomnias. The most clinically significant variant is rapid eye movement sleep behaviour disorder, characterised by loss of normal muscle paralysis that occurs during rapid eye movement sleep, allowing individuals to physically act out their dreams with potentially violent or injurious behaviours.

This condition primarily affects older adults, particularly men over age 50, and has gained clinical attention due to its strong association with neurodegenerative diseases, particularly conditions affecting dopamine-producing brain regions. The condition often precedes development of other neurological symptoms by years or decades, making it a potential early marker for these conditions.

Sleep-related movement disorders encompass conditions characterised by abnormal movements that occur primarily during sleep or are exacerbated by sleep. Restless legs syndrome represents the most prevalent sleep-related movement disorder, involving uncomfortable sensations in the legs described as creeping, crawling, or electric feelings that occur primarily during periods of rest or inactivity and are temporarily relieved by movement.

These symptoms often interfere with sleep initiation and can lead to chronic insomnia that persists even when underlying sensations are addressed. The prevalence of restless legs syndrome increases with age and demonstrates higher rates in individuals over 60 years, though the condition can occur at any age. The disorder may relate to iron deficiency and can associate with kidney failure, Parkinson’s disease, diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, and pregnancy.

Sleep bruxism represents another important sleep-related movement disorder characterised by repetitive jaw muscle activity involving clenching or grinding of teeth during sleep. The condition affects a significant portion of the population and can lead to dental damage, jaw pain, headaches, and disruption of bed partner sleep. Sleep bruxism typically occurs during non-rapid eye movement sleep stages and may associate with other sleep disorders such as sleep apnea.

How Do Sleep Disorders Affect Mental Health and Overall Wellbeing?

The relationship between sleep disorders and mental health conditions represents one of the most clinically significant and complex areas in sleep medicine, with bidirectional influences that can profoundly impact overall wellbeing and quality of life. These interconnections demonstrate that sleep disturbances often serve as both symptoms and risk factors for psychiatric conditions, while mental health disorders can significantly exacerbate sleep problems and complicate recovery processes.

The association between chronic insomnia and mood disorders has been extensively documented across multiple populations and age groups. Research indicates that individuals with persistent insomnia demonstrate significantly elevated risks for developing anxiety disorders and major depressive disorder, with these associations remaining strong even after controlling for demographic factors and other potential confounding variables. The magnitude of this relationship proves substantial, with chronic insomnia increasing the risk of subsequent depression by 2-4 fold and anxiety disorders by 3-6 fold compared to individuals without sleep difficulties.

Major depressive disorder demonstrates particularly complex relationships with sleep disturbances that extend beyond simple symptom presentations. While insomnia has traditionally been viewed as a symptom of depression, emerging evidence suggests that sleep disturbances may represent independent risk factors for depression development, relapse, and resistance to standard interventions. Studies indicate that 20-44% of individuals with major depressive disorder continue to experience significant sleep difficulties despite otherwise effective management, and this residual insomnia associates with increased risks of depressive relapse and continued functional impairment.

The relationship between sleep disturbance and suicidal ideation represents one of the most concerning connections in this domain. At least 32 studies across multiple countries and age groups have identified significant associations between sleep problems and suicidal thoughts, suicide attempts, and completed suicide. These associations persist even after controlling for depression severity, suggesting that sleep disturbance may represent an independent risk factor for suicidality rather than simply a symptom of underlying depression.

Anxiety disorders demonstrate strong bidirectional relationships with sleep disturbances, creating cycles where anxiety interferes with sleep initiation and maintenance while sleep deprivation exacerbates anxiety symptoms and reduces coping capacity. Individuals with generalised anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder commonly experience sleep difficulties including prolonged sleep onset time, frequent awakening, non-restorative sleep, and nightmares that replay distressing experiences.

Post-traumatic stress disorder presents particularly complex sleep-related challenges, with sleep disturbances representing core features of the condition rather than secondary symptoms. Post-traumatic stress disorder-related sleep problems include recurrent nightmares that replay traumatic events, difficulty falling asleep due to hypervigilance, frequent awakening associated with autonomic arousal, and avoidance of sleep due to fear of nightmares or loss of control during sleep states.

The impact of sleep disorders extends beyond mental health to affect cognitive performance, physical health, and social relationships. Chronic sleep deprivation can disrupt hormone production that regulates appetite, leading to overeating behaviours and weight gain that compound health risks. The psychological consequences include increased levels of impatience, irritability, depression, and anxiety, creating complex interplay between sleep disturbance and emotional regulation that requires comprehensive approaches addressing both domains simultaneously.

Sleep disorders in pediatric populations present unique challenges that differ substantially from adult presentations due to developmental factors, age-related normal sleep patterns, and the influence of neurodevelopmental conditions. Sleep problems affect approximately 3-36% of typically developing children and adolescents, but this figure increases dramatically to up to 75% in children with neurodevelopmental, emotional, behavioural, and intellectual disorders, highlighting the complex bidirectional relationship between sleep and development.

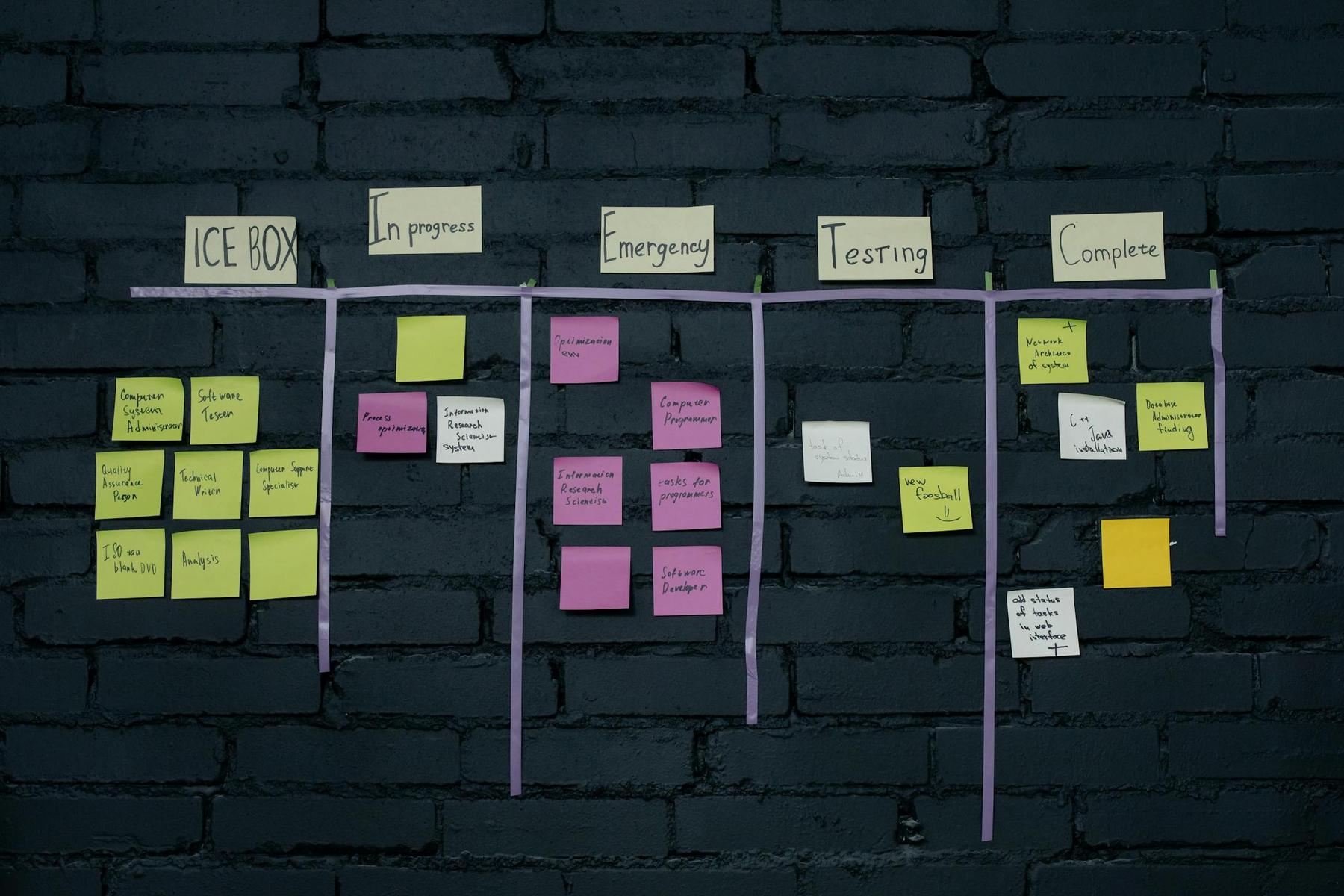

The assessment of patients presenting with either sleep disorders or mental health conditions should routinely include comprehensive evaluation of both domains, as the presence of comorbid conditions significantly influences prognosis and monitoring approaches. Sleep disturbances may serve as early warning signs for psychiatric relapse, while improvements in sleep quality often predict better outcomes in mental health recovery processes.

Understanding the Path Forward for Sleep Health in Australia

The comprehensive examination of sleep disorders reveals their profound impact on Australian society, affecting not only the 1.5 million individuals with diagnosed conditions but also the broader community through economic burden, safety concerns, and healthcare system strain. The evidence demonstrates that sleep disorders represent serious medical conditions requiring the same systematic approach and resource allocation as other chronic diseases with comparable prevalence and impact.

The substantial gap between prevalence and healthcare utilisation indicates significant opportunities for improvement in recognition, diagnosis, and management of sleep disorders across Australia. Primary care providers play an increasingly critical role in addressing this gap, as they represent the first point of contact for most individuals experiencing sleep difficulties. The development of screening protocols, clinical decision support tools, and collaborative relationships with sleep specialists can enhance the capacity of healthcare systems to meet the substantial need for sleep disorder services.

The interconnected nature of sleep disorders with mental health conditions, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and other chronic conditions underscores the importance of integrated care approaches that address sleep health as part of comprehensive medical management. Recognition of sleep disturbances as both risk factors and consequences of other medical conditions can improve outcomes across multiple domains of health while potentially reducing long-term healthcare costs.

The economic implications of sleep disorders, exceeding $36 billion annually when accounting for both direct costs and quality of life impacts, demonstrate the potential return on investment for improved sleep health initiatives. Early identification and appropriate management of sleep disorders can prevent progression to more severe conditions, reduce the development of associated comorbidities, and improve productivity and safety outcomes that benefit both individuals and society.

Public health approaches focusing on sleep education, sleep hygiene promotion, and early identification of sleep disorders represent important strategies for reducing the population burden of these conditions. Educational initiatives targeting both the general public and healthcare providers can improve recognition of sleep disorders and reduce barriers to seeking appropriate care.

The future of sleep medicine in Australia requires continued investment in research, clinical services, and public health initiatives that address sleep disorders as a priority health concern. The development of innovative approaches including technology-based solutions, integrated care models, and precision medicine approaches offers promise for improving outcomes while managing resource constraints.

Understanding sleep disorders as complex medical conditions with wide-ranging health implications represents the foundation for developing effective strategies to address this significant public health challenge. The evidence clearly supports increased attention to sleep health as a means of improving individual outcomes while reducing healthcare costs and societal burden across multiple domains.

What are the warning signs that indicate a sleep problem requires professional evaluation?

Warning signs that warrant professional evaluation include persistent difficulty falling asleep or staying asleep for more than three nights per week over several months, excessive daytime sleepiness that interferes with daily activities, loud snoring accompanied by gasping or choking sounds, witnessed breathing interruptions during sleep, and unusual behaviours during sleep such as sleepwalking or acting out dreams. Additional indicators include morning headaches, difficulty concentrating, memory problems, mood changes, or falling asleep at inappropriate times such as while driving.

How do sleep disorders differ from occasional sleep problems that most people experience?

Sleep disorders are distinguished from occasional sleep problems by their persistence, severity, and impact on daytime functioning. Unlike temporary sleep difficulties due to stress or environmental factors, sleep disorders involve chronic patterns lasting weeks to months that significantly impair daily activities, work performance, relationships, or safety. They typically involve specific physiological or neurological mechanisms requiring targeted interventions.

What role does age play in the development and presentation of different sleep disorders?

Age significantly influences both the types and prevalence of sleep disorders. Children may experience parasomnias such as sleepwalking and sleep terrors, which often resolve as they grow. Teenagers might develop delayed sleep phase patterns, while adults have increased risks of conditions like obstructive sleep apnea, particularly with aging and weight gain. Older adults often encounter higher rates of restless legs syndrome and other sleep disorders related to medical conditions and changes in sleep architecture.

How do sleep disorders impact workplace productivity and safety in Australia?

Sleep disorders contribute significantly to reduced workplace productivity and safety. In Australia, sleep disorders are linked to higher rates of absenteeism, presenteeism, and decreased work performance, with estimates suggesting up to $3.1 billion in annual productivity losses. The excessive daytime sleepiness and cognitive impairments associated with untreated sleep disorders increase the risk of workplace accidents and motor vehicle incidents.

When should parents be concerned about their child’s sleep patterns and seek professional help?

Parents should seek professional evaluation if their child consistently resists bedtime, takes longer than 30 minutes to fall asleep, wakes frequently during the night, experiences recurring nightmares, or exhibits unusual behaviours during sleep. Additional concerns include loud snoring, signs of breathing difficulties, or daytime issues such as significant sleepiness, behavioral problems, or academic challenges that may be linked to poor sleep.