The human brain’s relentless demand for rest manifests in peculiar ways when denied adequate sleep. Imagine driving along Melbourne’s M1 motorway during peak commute, your eyes fixed on the road ahead, when suddenly you realise several seconds have passed without any memory of the journey. Your vehicle has travelled approximately 100 metres whilst your consciousness flickered off and on like a faulty light switch. This terrifying phenomenon—microsleep—represents one of the most dangerous yet least understood aspects of sleep deprivation, affecting countless Australians who navigate the delicate balance between demanding schedules and biological necessity.

Microsleep episodes constitute a critical intersection between neuroscience, public safety, and occupational health. These involuntary lapses in consciousness, lasting anywhere from a fraction of a second to 30 seconds, occur when sleep-deprived individuals attempt to maintain wakefulness despite their brain’s desperate need for rest. The phenomenon transcends simple drowsiness, representing a neurological imperative that overrides conscious intention. Understanding microsleep requires examining the intricate mechanisms of sleep regulation, the cascading consequences of sleep debt, and the sophisticated ways our brains attempt to protect themselves from chronic deprivation.

What Is Microsleep and How Does It Occur?

Microsleep represents an involuntary physiological response wherein the brain briefly transitions into a sleep state whilst an individual remains ostensibly awake. These episodes typically last between 0.5 and 30 seconds, though the person experiencing them often remains unaware of their occurrence. During a microsleep event, portions of the brain enter a sleep-like state characterised by specific neural activity patterns, whilst other regions may maintain varying degrees of wakefulness.

The neurological architecture underlying microsleep involves complex interactions between multiple brain systems. Research has identified distinctive wave patterns that emerge as the brain transitions between sleep and wakefulness, suggesting that microsleep episodes represent localised sleep phenomena rather than global brain states. This partial engagement of sleep mechanisms explains why individuals may continue performing automatic tasks whilst experiencing microsleep, yet completely fail to register new information or respond to changing environmental conditions.

The phenomenon differs fundamentally from standard drowsiness or momentary distraction. Electroencephalography studies reveal that during microsleep, brain activity displays characteristics typically associated with sleep stages, including theta wave patterns and reduced responsiveness to external stimuli. The eyes may remain open or partially open, creating the illusion of wakefulness whilst neural processing capabilities become severely compromised.

Sleep pressure accumulates through the extended duration of wakefulness, driven by biochemical processes within the brain. As this pressure intensifies without relief through proper sleep, the brain begins implementing increasingly aggressive strategies to obtain rest, culminating in microsleep episodes that occur regardless of environmental circumstances or voluntary resistance. This represents the brain’s non-negotiable demand for recovery, overriding conscious control systems.

What Causes Microsleep Episodes?

The primary catalyst for microsleep episodes is chronic sleep deprivation, which encompasses both insufficient sleep duration and poor sleep quality. The Australian adult population faces mounting sleep challenges, with demanding work schedules, extended commutes, digital device usage, and societal expectations creating a perfect storm for accumulated sleep debt. When individuals consistently obtain less than the recommended seven to nine hours of quality sleep per night, their neurological systems begin operating under duress.

Sleep debt functions cumulatively, meaning that missing even one hour of sleep per night creates a mounting deficit that cannot be easily remedied through weekend recovery sleep. This accumulated deficit progressively impairs the brain’s ability to maintain consistent wakefulness, particularly during periods of reduced stimulation or monotonous activities. The homeostatic sleep drive—the biological pressure to sleep that builds during wakefulness—becomes increasingly difficult to resist as sleep debt grows.

Circadian rhythm disruptions contribute significantly to microsleep susceptibility. The human body operates according to an internal biological clock that regulates sleep-wake cycles, hormone production, and numerous physiological processes. Shift workers, individuals experiencing jet lag, or those maintaining irregular sleep schedules face heightened microsleep risk because their activities misalign with their circadian programming. The body’s natural dip in alertness, which occurs typically between 2:00 AM and 6:00 AM and again between 2:00 PM and 4:00 PM, represents periods of particular vulnerability.

Underlying sleep disorders dramatically increase microsleep frequency and severity. Conditions affecting sleep architecture, breathing patterns during sleep, or sleep continuity prevent individuals from obtaining restorative rest despite spending adequate time in bed. These disorders create a state of chronic sleep deprivation even when sleep duration appears sufficient, as the quality and efficiency of sleep remain compromised.

Environmental factors and lifestyle choices further exacerbate microsleep risk. Prolonged periods of monotonous activity, such as highway driving or repetitive work tasks, reduce external stimulation that helps maintain alertness. Sedentary positions, warm environments, and post-meal periods naturally promote drowsiness, lowering the threshold for microsleep occurrence in sleep-deprived individuals.

How Can You Recognise the Signs of Microsleep?

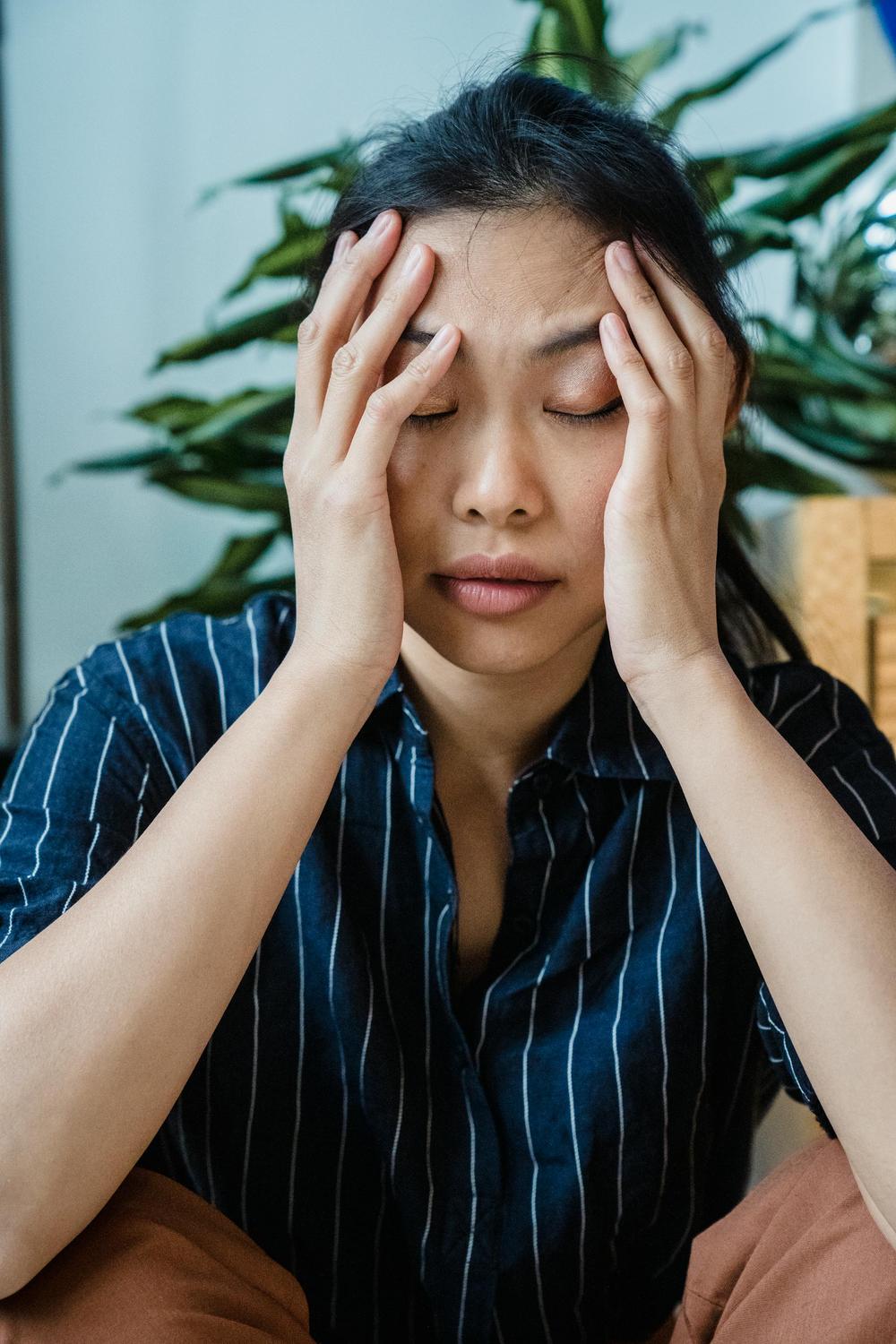

Identifying microsleep episodes presents considerable challenges because they often occur without conscious awareness. The brief nature of these events, combined with their tendency to arise during activities requiring sustained attention, means individuals frequently experience microsleep without recognising the lapse. However, several characteristic signs can help identify both active microsleep episodes and warning signals that precede them.

During a microsleep episode, the most prominent feature involves a complete lapse in awareness and responsiveness. The individual may exhibit blank staring, with eyes remaining open but displaying reduced blinking or a glazed appearance. Head nodding or sudden head drops represent common physical manifestations, as muscle tone temporarily decreases during the sleep transition. Some individuals experience eye closure or prolonged blinks lasting several seconds, creating obvious visual indicators of the episode.

| Microsleep Indicators | Observable Signs | Internal Experience | Duration Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Microsleep warning signs | Heavy eyelids, frequent yawning, difficulty focusing vision | Intrusive sleepiness, inability to concentrate, wandering thoughts | Seconds to minutes before episode |

| During Microsleep | Blank staring, head nodding, reduced responsiveness, slow eyelid closure | No awareness, complete lapse in consciousness | 0.5 to 30 seconds |

| Post-Microsleep | Disorientation, jerking movements, compensatory alertness | Confusion about time passage, memory gaps | Immediate seconds after |

| Functional Impact | Failure to respond to stimuli, inability to recall events | Lost time, incomplete task execution | Variable depending on activity |

Individuals who become aware of their microsleep episodes often describe experiencing sudden confusion or disorientation, accompanied by an inability to recall events from the preceding seconds. This memory gap serves as a hallmark feature distinguishing microsleep from simple inattention. The person may notice having drifted from their lane whilst driving, missed portions of conversation, or lost their place in a task without conscious awareness of the interruption.

Warning signs preceding microsleep provide crucial opportunities for intervention. Persistent yawning, increasingly heavy eyelids, difficulty maintaining focus, and a sensation of head heaviness signal mounting sleep pressure. Visual disturbances, including difficulty focusing or maintaining clear vision, indicate that the brain’s visual processing centres are beginning to disengage. Some individuals report experiencing brief hallucinations or dreamlike thoughts intruding into waking consciousness, suggesting the boundaries between sleep and wakefulness are becoming permeable.

Behavioural changes accompanying microsleep vulnerability include decreased responsiveness to environmental stimuli, slowed reaction times, and diminished performance on tasks requiring sustained attention. Individuals may begin making uncharacteristic errors, exhibiting irritability, or demonstrating reduced motivation as their cognitive resources become increasingly compromised.

What Are the Risks and Consequences of Microsleep?

The dangers associated with microsleep extend far beyond temporary inconvenience, encompassing potentially catastrophic outcomes across multiple domains of human activity. The most immediately threatening scenarios involve operation of vehicles or machinery, where momentary lapses in consciousness can produce irreversible consequences. When microsleep occurs during driving, even a three-second episode at 100 kilometres per hour results in the vehicle travelling approximately 83 metres without conscious control—sufficient distance for catastrophic collision.

Australian road safety data consistently identifies driver fatigue and drowsiness as significant contributors to motor vehicle accidents. The mechanisms underlying these crashes often involve microsleep episodes rather than drivers falling fully asleep at the wheel. The insidious nature of microsleep means drivers may experience multiple brief episodes whilst continuing to operate their vehicles, creating a false sense of maintained control despite severe impairment. Rural highways and monotonous driving conditions present particular risk, as the reduced stimulation and extended driving durations combine with circadian vulnerability periods.

Workplace safety implications prove equally concerning across numerous industries and occupational settings. Healthcare workers, transportation operators, manufacturing personnel, and emergency responders all face heightened risks when microsleep episodes compromise their vigilance and decision-making capabilities. The consequences may include medical errors, industrial accidents, compromised security monitoring, and failures in safety-critical systems. Shift work patterns common in these industries further compound microsleep risk through circadian disruption and accumulated sleep debt.

Beyond acute safety risks, chronic microsleep occurrence indicates sustained sleep deprivation that affects broader health and cognitive functioning. Sleep debt associated with frequent microsleep episodes impairs memory consolidation, learning capacity, emotional regulation, and executive function. The body’s metabolic, cardiovascular, and immune systems all suffer when adequate restorative sleep remains chronically elusive. Individuals experiencing regular microsleep episodes operate at substantially reduced cognitive capacity compared to their well-rested baseline, affecting professional performance, interpersonal relationships, and overall quality of life.

The social and economic costs of microsleep-related incidents extend throughout Australian communities. Workplace productivity losses, healthcare expenditures, property damage, and the immeasurable human toll of preventable accidents all stem from inadequate recognition and management of sleep deprivation. Understanding these consequences emphasises the critical importance of prioritising sleep health and recognising microsleep episodes as indicators of serious underlying sleep deficit.

How Can Microsleep Be Prevented?

Preventing microsleep requires addressing the fundamental cause: inadequate sleep. The most effective strategy involves prioritising consistent, sufficient sleep duration and quality. Adults should target seven to nine hours of sleep per night, maintaining regular sleep-wake schedules even on weekends. This consistency reinforces circadian rhythms and prevents the accumulation of sleep debt that precipitates microsleep episodes.

Creating optimal sleep environments supports better sleep quality and efficiency. Bedrooms should maintain cool temperatures (approximately 18-20 degrees Celsius), minimal light exposure, and reduced noise levels. Removing electronic devices that emit blue light and establishing pre-sleep routines that promote relaxation help facilitate the transition to sleep. The sleep environment should be reserved primarily for sleep and intimacy, reinforcing the psychological association between the bedroom and rest.

Managing sleep schedules around natural circadian rhythms enhances sleep quality and reduces microsleep susceptibility. Individuals should aim for consistent sleep timing that aligns with their natural chronotype—whether they function better as morning larks or night owls. Exposure to bright light during morning hours and reduced light exposure in evening hours helps maintain robust circadian signalling.

When microsleep warning signs emerge during activities requiring sustained attention, immediate countermeasures become essential. For drivers experiencing drowsiness, the only truly effective response involves ceasing driving and obtaining rest. Brief naps of 15-20 minutes can provide temporary alertness restoration, though they represent short-term solutions rather than substitutes for adequate nocturnal sleep.

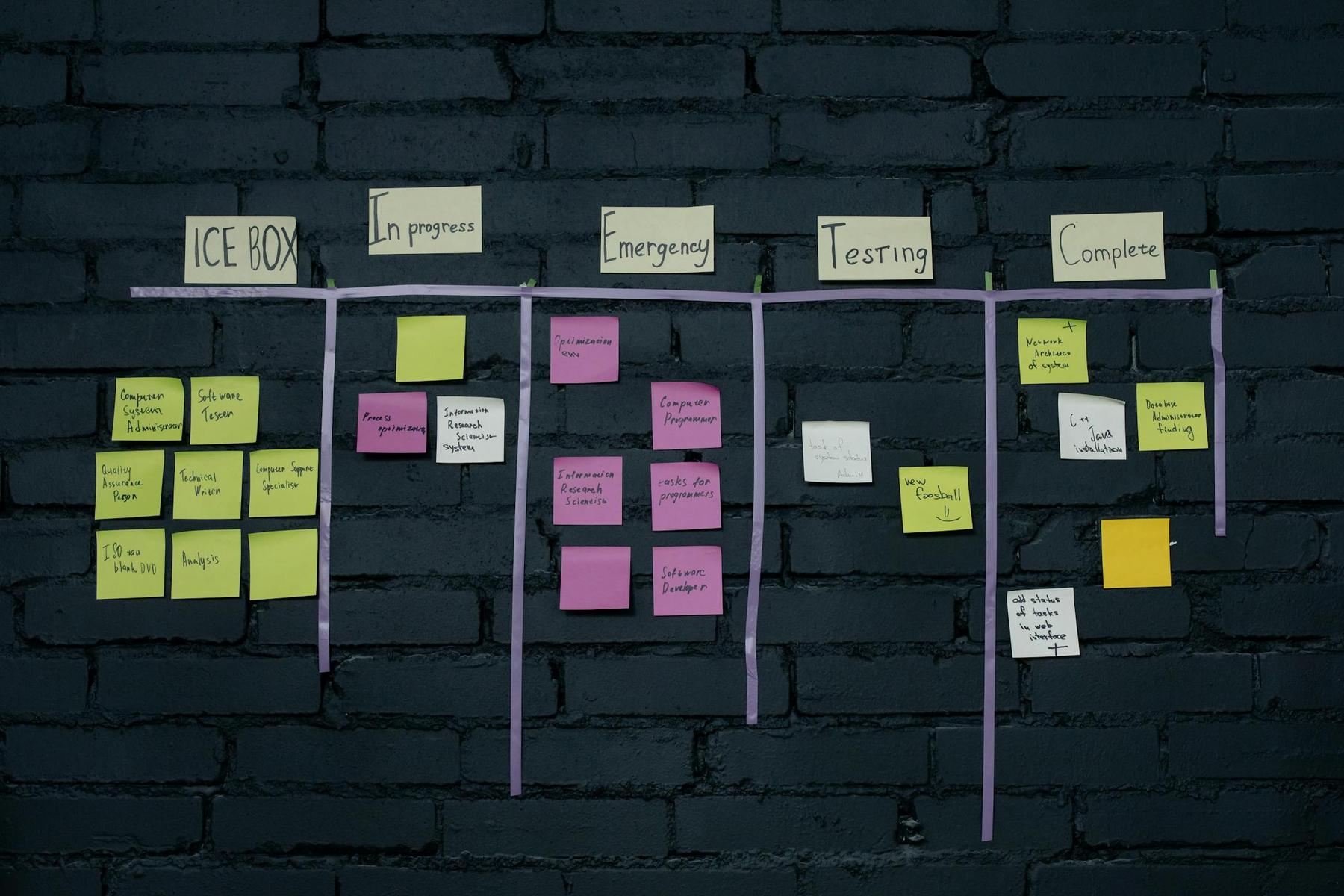

Workplace strategies for microsleep prevention include implementing fatigue risk management systems, particularly in industries involving shift work or extended duty periods. Strategic scheduling that considers circadian rhythms, adequate rest breaks, and workload management reduces microsleep risk. Education programmes that help workers recognise fatigue signs and understand the limitations of willpower in overcoming sleep deprivation prove valuable across occupational settings.

Lifestyle factors supporting better sleep health include regular physical activity (completed several hours before bedtime), balanced nutrition, stress management practices, and limitation of substances that disrupt sleep architecture. Establishing boundaries around work demands, digital engagement, and social commitments allows adequate time allocation for sleep.

When Should You Seek Professional Guidance?

Persistent microsleep episodes despite adequate sleep opportunity warrant professional evaluation. When individuals consistently allocate sufficient time for sleep yet continue experiencing involuntary sleep episodes, underlying sleep disorders may be present. These conditions require specific diagnostic approaches and management strategies beyond basic sleep hygiene improvements.

Several circumstances indicate the need for consultation with sleep specialists or healthcare professionals. Experiencing microsleep episodes multiple times per week, particularly if they occur during high-risk activities like driving or working with machinery, represents an urgent concern requiring prompt attention. Individuals who feel chronically unrefreshed despite seemingly adequate sleep duration, exhibit loud snoring or breathing interruptions during sleep, or experience excessive daytime sleepiness that interferes with daily functioning should pursue professional evaluation.

Comprehensive sleep assessment may involve sleep diaries documenting sleep patterns, validated questionnaires measuring sleepiness and sleep quality, and potentially overnight sleep studies. These diagnostic approaches help identify specific sleep disorders, circadian rhythm abnormalities, or other factors contributing to microsleep vulnerability. Early identification and appropriate management of underlying sleep conditions can dramatically improve both safety outcomes and overall quality of life.

Healthcare professionals with expertise in sleep physiology can provide evidence-based guidance tailored to individual circumstances. This personalised approach considers unique risk factors, lifestyle constraints, occupational demands, and health status when developing strategies to improve sleep health and reduce microsleep occurrence. The multifaceted nature of sleep problems often requires comprehensive approaches that address biological, psychological, and environmental contributors.

Individuals working in safety-critical roles or experiencing microsleep during potentially dangerous activities should not delay seeking professional input. The risks associated with continued microsleep episodes during these circumstances far outweigh concerns about time investment or perceived inconvenience of pursuing evaluation. Proactive management of sleep health represents an investment in both personal safety and long-term wellbeing.

Moving Forward With Sleep Awareness

Microsleep represents a profound neurological signal demanding attention—a biological alarm indicating that sleep debt has reached unsustainable levels. These involuntary lapses in consciousness reveal the brain’s non-negotiable requirement for adequate rest, demonstrating that willpower alone cannot override fundamental physiological needs. Recognition of microsleep episodes and their warning signs empowers individuals to make informed decisions prioritising safety and health.

The prevalence of microsleep throughout modern Australian society reflects broader cultural attitudes that often undervalue sleep’s essential role in human functioning. Changing these patterns requires both individual commitment to sleep health and systemic recognition of sleep as a critical component of workplace safety, public health, and overall wellbeing. Education about microsleep dangers, combined with practical strategies for prevention and intervention, can reduce the substantial toll these episodes exact across our communities.

Understanding that microsleep episodes signal serious underlying sleep deprivation rather than simple laziness or weakness represents an important shift in perspective. Sleep constitutes an active biological process essential for physical health, cognitive function, emotional regulation, and optimal human performance. Treating sleep with the respect and priority it deserves creates foundations for safer roads, more productive workplaces, and healthier individuals throughout Australia.

The journey towards better sleep health begins with acknowledging current patterns, recognising warning signs, and implementing evidence-based strategies that support consistent, restorative sleep. Whether through environmental modifications, schedule adjustments, or professional consultation, numerous pathways exist for improving sleep and reducing microsleep vulnerability. The investment in sleep health yields dividends across every aspect of life, enhancing not only safety but also performance, relationships, and overall life satisfaction.

Can microsleep occur without you knowing it?

Yes, microsleep episodes frequently occur without conscious awareness. Many individuals experience these brief lapses and only recognise them retrospectively through memory gaps, missed information, or positional changes they cannot recall. The brief duration of microsleep, combined with its tendency to occur during automatic tasks, allows these episodes to escape immediate detection. Warning signs like heavy eyelids, frequent yawning, and difficulty concentrating often precede microsleep, providing opportunities for recognition before episodes occur.

How long do microsleep episodes typically last?

Microsleep episodes typically last between 0.5 and 30 seconds, though most occur within the 1-15 second range. Even episodes lasting only a few seconds can have serious consequences, particularly during activities requiring sustained attention such as driving or operating machinery. A three-second microsleep at highway speeds results in a vehicle travelling over 80 metres without conscious control.

Is microsleep the same as nodding off or feeling drowsy?

No, microsleep differs fundamentally from general drowsiness or voluntarily nodding off. Drowsiness represents a state of reduced alertness where individuals remain conscious and maintain some degree of control over their attention, whereas microsleep involves involuntary transitions into actual sleep states that override conscious control.

What makes someone more susceptible to experiencing microsleep?

Chronic sleep deprivation, irregular sleep schedules, and circadian rhythm disruptions are among the primary factors that increase susceptibility to microsleep. Accumulated sleep debt impairs the brain’s ability to maintain wakefulness, making individuals more vulnerable during monotonous activities and in situations that require sustained attention.