Deep within the centre of your brain, nestled between the two cerebral hemispheres, lies a tiny pinecone-shaped gland that orchestrates one of your body’s most fundamental processes: the regulation of sleep and wakefulness. Despite weighing merely 0.1 grams and measuring just 5-8 millimetres in length—roughly the size of a grain of rice—the pineal gland wields extraordinary influence over your circadian rhythms, hormonal balance, and overall wellbeing. For the 59.4% of Australian adults experiencing sleep symptoms at least three times weekly, and the 23.2% diagnosed with chronic insomnia, understanding this remarkable endocrine gland has never been more relevant. The pineal gland’s capacity to produce the pineal sleep-regulating hormone represents a sophisticated biological system that has evolved over millions of years to synchronise our internal physiology with the external environment.

What Is the Pineal Gland and Where Is It Located?

The pineal gland occupies a unique position within the brain’s architecture, situated in the epithalamus region of the diencephalon. Specifically positioned above the thalamus and beneath the corpus callosum, it sits between the superior colliculi—the midbrain structures responsible for visual reflexes. This central location places the gland at the anatomical crossroads of critical neural pathways.

Remarkably, the pineal gland exists outside the blood-brain barrier, a characteristic shared by few brain structures. This exceptional positioning allows the gland direct access to circulating hormones and enables its secretions to reach all body tissues efficiently. The gland receives extraordinarily high blood flow—second only to the kidneys when comparing blood supply relative to tissue mass—through posterior choroidal arteries, branches of the posterior cerebral arteries.

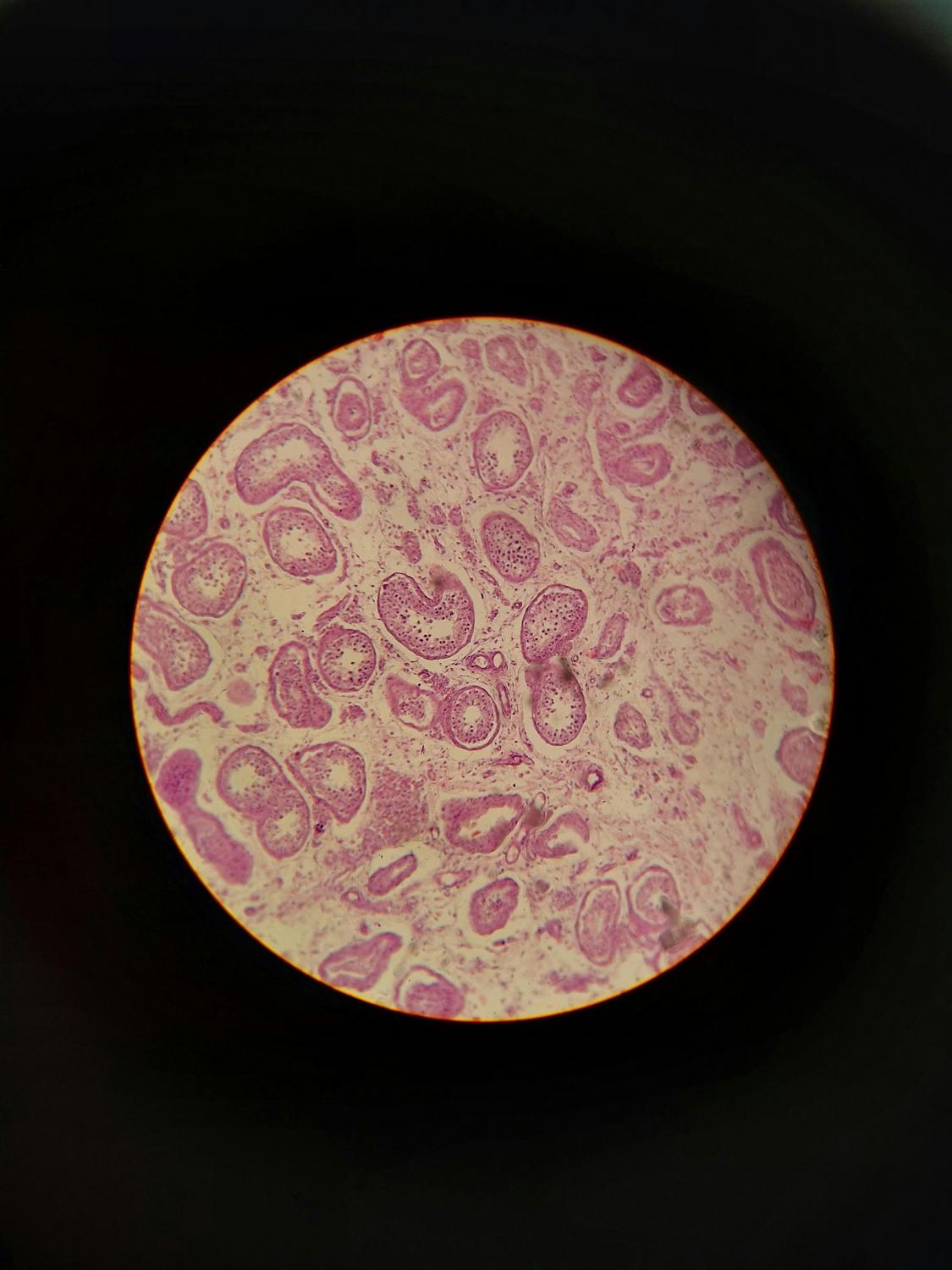

The cellular composition reveals a highly specialised organ: approximately 95% of the gland consists of pinealocytes, specialised secretory cells responsible for hormone production and release. The remaining 5% comprises glial cells, including astrocytic and phagocytic subtypes that provide essential supportive functions. This dense network of fenestrated capillaries throughout the gland facilitates rapid hormone distribution throughout the body’s systems.

How Does the Pineal Gland Produce Sleep Hormones?

The pineal gland’s primary function centres on the synthesis and secretion of the pineal sleep-regulating hormone. This synthesis is controlled by specialised neural pathways that respond to environmental light-dark cycles, representing an elegant integration of external environmental signals with internal physiology.

What Neural Pathways Regulate Pineal Gland Function?

The regulation of pineal gland activity represents one of neuroscience’s most elegant examples of environmental integration with internal physiology. This control system begins with specialised light-sensitive cells in the retina, continues through the brain’s master circadian pacemaker, and culminates in the rhythmic release of the sleep-regulating hormone.

The Retinohypothalamic Tract and Light Detection

Intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells (ipRGCs) within the eye contain melanopsin, a photopigment particularly responsive to blue wavelengths between 460 and 480 nanometres. These cells detect ambient light levels and transmit this information via the retinohypothalamic tract to the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) located in the hypothalamus. The SCN functions as the body’s master clock, containing clock genes—Clock, Bmal1, Per1-3, and Cry1-2—that generate an endogenous rhythm with a period of approximately 24.2 to 24.5 hours.

When light exposure occurs, the SCN releases gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), which inhibits neurons in the paraventricular nucleus (PVN). This inhibition blocks the downstream signal cascade that would otherwise activate hormone synthesis. Conversely, during darkness, the SCN releases glutamate instead, activating the PVN and initiating a descending neural pathway.

The Descending Neural Cascade

This pathway proceeds from the PVN to the intermediolateral nucleus (IML) of the spinal cord, which then projects to the superior cervical ganglion (SCG). The SCG releases norepinephrine to the pineal gland, triggering the activation of hormone synthesis. Damage to the SCN results in the loss of the majority of circadian rhythms, underscoring its critical role as the body’s temporal conductor.

The precision of this system explains why even relatively low light intensities can suppress hormone production—light exposure as low as 60-130 lux can inhibit synthesis, whilst standard office lighting at 350-500 lux substantially reduces nighttime hormone levels.

How Do Circadian Rhythms Influence Sleep Hormone Production?

The daily fluctuation of sleep hormone secretion follows a remarkably consistent pattern in healthy individuals. This pattern reveals the intimate relationship between environmental light cycles and internal biological timing.

The Daily Hormone Cycle

During daylight hours, sleep hormone concentrations remain at baseline levels. As evening approaches and environmental light diminishes, hormone synthesis begins approximately 90-120 minutes before an individual’s habitual sleep time. This gradual increase accelerates throughout the dark period, reaching peak concentrations between 2:00 and 4:00 AM. Morning light exposure rapidly suppresses synthesis, causing hormone levels to decline as dawn approaches.

The magnitude of this daily variation is substantial: nighttime hormone concentrations exceed daytime levels by approximately 10-fold. This dramatic oscillation provides a powerful biological signal that coordinates sleep-wake behaviour with the solar cycle. The hormone’s effects extend beyond simple drowsiness, influencing core body temperature regulation and promoting both rapid eye movement (REM) and slow-wave sleep, the deep sleep stage crucial for physical restoration and memory consolidation.

Light Sensitivity and Modern Challenges

The exquisite sensitivity of this system to light presents significant challenges in contemporary environments. Blue light wavelengths, particularly prevalent in electronic screens, represent the most potent suppressors of hormone synthesis. Evening room light exposure can substantially shorten hormone duration, whilst full-spectrum bright light at 2,500 lux achieves complete nighttime hormone suppression.

For Australians, where 40% report insufficient sleep and sleep-related issues cost the economy $75.5 billion annually, understanding these light-mediated effects becomes crucial. Screen time before bed, characteristic of modern lifestyles, directly undermines the pineal gland’s natural rhythm, delaying sleep onset and reducing sleep quality.

What Factors Can Impair Pineal Gland Function?

Numerous environmental, behavioural, and pathological factors can compromise the pineal gland’s capacity to produce sleep hormones adequately, leading to sleep disturbances and broader health consequences.

Age-Related Changes in Sleep Hormone Production

Perhaps the most universal factor affecting pineal function is ageing. Newborns do not produce the sleep-regulating hormone endogenously, receiving it through the placenta and breast milk. The hormone cycle develops at 3-4 months of age, with levels peaking between ages 1 and 3 years—the highest production humans experience throughout life. These levels remain stable through childhood and early adulthood, but a steady decline begins after age 40. By age 70 and beyond, hormone levels approximate 25% or less compared to young adults, partially explaining the increased sleep disturbances reported by older Australians.

Gender differences also emerge, with females typically maintaining higher hormone levels than males across all age groups, though both sexes experience the age-related decline.

Environmental and Lifestyle Factors

Shift work creates chronic circadian disruption, dissociating the sleep hormone rhythm from the natural 24-hour cycle. The approximately 1.4 million Australians working non-standard hours face particular challenges as their pineal glands attempt to synchronise with conflicting temporal cues. Jet lag represents an acute version of this misalignment, where the hormone rhythm remains locked to the origin time zone whilst the individual operates in a destination with different light-dark cycles.

Irregular sleep schedules prevent stable hormone entrainment, creating a state of perpetual jet lag without crossing time zones. Insufficient daytime light exposure reduces the strength of circadian signals, whilst excessive nighttime light exposure—especially blue-enriched light from digital devices—suppresses hormone production when synthesis should be maximal.

Pathological Conditions Affecting the Pineal Gland

Pineal gland calcification represents a common finding on radiological imaging, characterised by the accumulation of calcium and phosphate deposits that harden gland tissue. Whilst observable from childhood through elderly years, calcification increases with age and correlates with reduced hormone synthesis. Higher degrees of calcification associate with sleep problems, migraines, and appear more prevalent in individuals with neurodegenerative conditions.

Pineal tumours, whilst rare (representing less than 1% of intracranial tumours), can dramatically impact function. These tumours more commonly affect children and adults under 40 years, producing symptoms including headaches, vision changes, balance problems, and endocrine dysfunction as the growing mass compresses nearby brain structures.

Traumatic brain injury affects 30-50% of patients with endocrine gland dysfunction, including the pineal gland. Spinal cord injuries can sever the sympathetic innervation essential for hormone rhythm generation, abolishing the normal production cycle entirely.

How Does Pineal Gland Dysfunction Affect Sleep Quality?

The consequences of impaired pineal gland function extend far beyond simple difficulty falling asleep, affecting multiple dimensions of sleep architecture, daytime functioning, and long-term health outcomes.

Circadian Rhythm Sleep Disorders

Lower-than-normal nighttime hormone levels produce characteristic symptoms: insomnia, fragmented sleep, early morning awakening, and poor sleep quality despite adequate time in bed. This condition associates strongly with circadian rhythm sleep disorders, a category encompassing delayed sleep-wake phase disorder (where sleep onset occurs 2+ hours later than desired), advanced sleep-wake phase syndrome (sleep onset 2+ hours earlier than desired), and non-24-hour sleep-wake disorder, particularly prevalent amongst individuals without light perception.

These disorders reflect fundamental disconnection between the pineal gland’s hormone production timing and the individual’s desired or required sleep schedule. The consequences extend beyond nocturnal discomfort—chronic circadian misalignment increases risks of depression, cardiovascular disease, and metabolic dysfunction.

The Insomnia Epidemic in Australia

Clinical insomnia affects 14.8% of Australian adults, with characteristics including difficulty falling asleep (sleep-onset insomnia), difficulty maintaining sleep (sleep-maintenance insomnia), early morning awakening, and non-restorative sleep despite adequate opportunity. Research demonstrates that reduced pineal gland volume correlates with insomnia severity, suggesting structural changes may underlie functional impairment in hormone production.

Gender differences emerge prominently: insomnia affects 25.2% of Australian females compared to 21.1% of males. Women experience earlier sleep disturbances during menopause, correlating with hormonal changes that may affect pineal gland function and hormone synthesis.

The economic burden proves staggering—Australia’s $75.5 billion annual expenditure on sleep-related health costs represents a 14% increase from 2016-2017 figures. This includes $1.24 billion in direct healthcare costs, $3.1 billion in lost productivity, and $650 million in accident-related costs. Yet despite these substantial impacts, only 7.5% of individuals with insomnia receive medical diagnosis, and fewer than 1% access cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia (CBT-i), considered the gold-standard treatment.

Beyond Sleep: Broader Health Effects of Pineal Gland Dysfunction

The sleep-regulating hormone’s functions extend considerably beyond sleep regulation. The hormone functions as a potent free radical scavenger, providing antioxidant protection throughout the body. Reduced hormone production therefore compromises antioxidant defences.

The cardiovascular system particularly depends on adequate hormone levels, with the gland coordinating the normal nocturnal blood pressure reduction. Immune function also responds to the sleep-regulating hormone through multiple pathways. Reproductive hormones, glucose metabolism, and insulin sensitivity all show regulatory connections to pineal gland function, explaining why pineal gland dysfunction produces such diverse health consequences.

Understanding the Path Forward for Sleep Health

The pineal gland exemplifies biological elegance—a tiny endocrine organ that integrates environmental light information with internal physiology to orchestrate sleep-wake cycles and coordinate numerous physiological processes. Weighing merely 0.1 grams yet producing the pineal sleep-regulating hormone, this pinecone-shaped structure demonstrates that significance bears no relationship to size.

For Australians facing an epidemic of sleep disorders—with nearly 60% experiencing regular sleep symptoms and economic costs approaching $76 billion annually—understanding pineal gland function becomes more than academic interest. The SCN-pineal axis represents a modifiable system responsive to behavioural interventions: managing light exposure, maintaining consistent sleep schedules, and minimising blue light before bedtime all support optimal hormone production.

The research reveals remarkable precision in this biological timekeeper, with the sleep-regulating hormone showing exquisite sensitivity to light, whilst evolutionarily advantageous for synchronising with natural day-night cycles, creating vulnerability in modern environments saturated with artificial illumination.

Age-related decline in hormone production—reducing levels to 25% or less in individuals over 70 compared to young adults—partially explains increased sleep disturbances in older populations. Pineal gland calcification, traumatic brain injury, and structural abnormalities further compromise function, highlighting the gland’s physiological fragility despite its protected central location.

Australian healthcare faces significant challenges in addressing sleep disorders: fewer than 1% of insomnia sufferers access evidence-based cognitive behavioural therapy, only 37% discuss sleep problems with their general practitioner, and medical schools provide merely 6.2 hours of sleep medicine training. These systemic barriers prevent millions of Australians from receiving appropriate support for sleep disturbances rooted in circadian rhythm dysfunction.

The pineal gland thus stands as both a vulnerable target for modern lifestyle factors and a promising focus for interventions. Protecting its function through evidence-based behavioural modifications—appropriate light exposure timing, consistent sleep schedules, and reduced evening blue light exposure—represents accessible, cost-effective strategies for improving sleep health at individual and population levels.

How does blue light from screens affect pineal gland function?

Blue light wavelengths between 460-480 nanometres represent the most potent suppressors of pineal gland hormone production. Intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells in the eye contain melanopsin, specifically responsive to these wavelengths. Evening screen exposure signals the suprachiasmatic nucleus that daytime persists, inhibiting the neural pathway that triggers hormone synthesis. Minimising blue-enriched light exposure 2-3 hours before bedtime allows natural hormone production to proceed unimpeded.

At what age does pineal gland hormone production begin to decline?

Pineal hormone production begins to decline after age 40. Newborns do not synthesise the hormone endogenously, with production developing at 3-4 months and peaking between ages 1-3 years. After early adulthood, levels remain stable before beginning a steady decline post-40, with individuals over 70 having approximately 25% of the hormone levels observed in young adults. Females tend to maintain higher levels than males across age groups.

Can pineal gland calcification be prevented or reversed?

Pineal gland calcification, the accumulation of calcium and phosphate deposits within the gland, increases with age and correlates with reduced hormone synthesis. Although calcification is common and associated with sleep problems and migraines, there are currently no validated interventions to prevent or reverse it. Maintaining overall metabolic health, adequate hydration, and minimizing factors that disrupt calcium homeostasis are general approaches, though specific anti-calcification strategies are not well established.

What is the relationship between shift work and pineal gland dysfunction?

Shift work creates chronic circadian disruption that conflicts with the pineal gland’s synchronisation to natural light-dark cycles. Workers often attempt to sleep when the gland is receiving signals to suppress hormone production, and remain awake when hormone levels naturally peak. This misalignment can lead to increased risks of sleep disorders, metabolic dysfunction, cardiovascular disease, and mood disturbances, as the pineal gland’s rhythm is slow to adjust to changing schedules.

How does the pineal gland affect functions beyond sleep regulation?

Beyond sleep regulation, the pineal gland influences multiple physiological systems. The sleep-regulating hormone acts as a potent antioxidant, supports immune function, aids in cardiovascular regulation by coordinating nocturnal blood pressure reduction, and plays a role in glucose metabolism and insulin sensitivity. Its broad regulatory effects underscore the importance of the gland in overall health.