In an era where mental wellbeing challenges have reached unprecedented levels across Australia and globally, ancient practices are experiencing remarkable scientific validation. Amongst these time-tested approaches, labyrinth walking stands as a uniquely accessible meditation practice—requiring no special equipment, extensive training, or athletic prowess. Yet despite its simplicity, this 3,000-year-old contemplative tradition demonstrates measurable physiological impacts that modern science is only beginning to fully comprehend. As individuals increasingly seek evidence-based alternatives to address stress, cognitive function, and emotional regulation, understanding the historical depth and contemporary applications of labyrinth walking becomes particularly relevant for those pursuing integrated approaches to wellbeing.

What Defines Labyrinth Walking as a Distinct Meditative Practice?

Labyrinth walking represents a fundamental departure from conventional meditation practices through its integration of physical movement with contemplative focus. Unlike mazes featuring multiple pathways, dead-ends, and decision points, a labyrinth comprises a single, continuous path leading from entrance to centre and back again—a unicursal design requiring no navigational choices. This absence of decision-making distinguishes the practice from both recreational walking and puzzle-solving activities.

The structural characteristics of traditional labyrinths follow precise specifications. The renowned Chartres Cathedral labyrinth, constructed between 1200-1221 CE, spans 12.895 metres in diameter with a total path length of approximately 262.4 metres. The walking surface averages 13.25 inches wide, separated by 3-inch walls forming eleven distinct circuits. This geometric precision reflects medieval sacred geometry principles, wherein the labyrinth’s placement between specific architectural elements represented theological concepts—the meeting of spirit (three) and matter (four) to create wholeness (seven).

Contemporary labyrinth walking follows a standardised three-phase structure validated through clinical research. The releasing phase involves walking inward whilst consciously releasing concerns and quieting mental chatter. Upon reaching the centre rosette—typically a flower-shaped focal point—participants enter the receiving phase, dedicating time to meditation or reflection. The final returning phase retraces the identical path outward, integrating insights and renewed perspective. This tripartite framework provides both structure and flexibility, accommodating diverse spiritual traditions and secular applications whilst maintaining the practice’s core contemplative elements.

How Does Labyrinth Walking Span 4,000 Years of Global History?

Archaeological evidence positions labyrinth symbols amongst humanity’s earliest recorded spiritual practices. Pottery fragments and rock carvings discovered throughout Southern Europe demonstrate labyrinth imagery dating 3,000-4,000 years ago, predating written historical records. The ancient Cretan labyrinth, Egyptian Labyrinth of Hawara (pyramid of Pharaoh Amenemhat III, 1860-1814 BCE), and Indian stone labyrinths from 250 BCE onwards reveal the practice’s geographical diversity across disparate civilisations with no apparent cultural contact.

Native American Tohono O’odham peoples incorporated labyrinth imagery in their “Man in the Maze” symbol, whilst Scandinavian coastal communities constructed over 500 stone labyrinths—primarily utilised by fishing communities in ritualistic practices. This global distribution across unconnected ancient cultures suggests labyrinth patterns represent archetypal human expressions—universal symbols encoded within collective consciousness transcending specific religious frameworks.

The medieval European period witnessed labyrinths’ dramatic transformation from outdoor mystical sites to integrated cathedral architecture. Beginning in Italian churches during the early 12th century, labyrinth construction proliferated throughout Northern France by century’s end. The grand flowering occurred between the 12th and 14th centuries, when Gothic cathedrals at Chartres, Reims, and Amiens incorporated magnificent pavement labyrinths as architectural and theological statements.

These cathedral labyrinths functioned as “Chemin de Jérusalem” (Path to Jerusalem)—substitute pilgrimages for individuals unable to undertake dangerous journeys to the Holy Land. Rather than mere decorative elements, they represented profound theological commitments: physical enactments of spiritual journeys toward divine connection. Easter celebrations sometimes featured ring-dances and chanting within the labyrinth circuits, documented at Auxerre Cathedral between 1396-1538, before ecclesiastical authorities eventually suppressed these more exuberant expressions.

The modern revival commenced in the 1990s through Reverend Dr. Lauren Artress’s pioneering work at Grace Cathedral, San Francisco. Her introduction of Chartres-pattern labyrinths and establishment of Veriditas (“The Voice of the Labyrinth Movement”) catalysed exponential growth. Today, over 6,400 labyrinths exist globally—including 3,800+ across the United States and growing numbers throughout Australia—demonstrating the practice’s remarkable contemporary relevance despite its ancient origins.

What Clinical Evidence Supports Labyrinth Walking’s Physiological Benefits?

Contemporary scientific investigation validates historical claims regarding labyrinth walking’s stress-reduction capabilities through quantifiable physiological markers. A 2017 workplace stress study examining 26 employees over eight weeks documented striking cortisol level reductions. Baseline measurements showed waking cortisol at 7.92 nmol/L and bedtime levels at 7.82 nmol/L. Following the labyrinth walking intervention, participants demonstrated 69% reduction in waking cortisol (2.42 nmol/L) and 59% reduction in bedtime cortisol (3.22 nmol/L)—representing large effect sizes for workplace stress interaction (η² = 0.13).

Research conducted at St. Joseph’s Southwest Centre for Forensic Mental Health Care revealed similarly compelling outcomes. Participants in labyrinth walking groups showed large effect sizes (Cohen’s d = 0.65) for perceived stress score reduction. The odds ratio for feeling “much more/more relaxed” following labyrinth walking reached 51.33 (95% CI 15.68-168.06), whilst odds of being “less/much less stressed” achieved 5.49 (95% CI 3.3-9.15). These statistical findings provide robust evidence distinguishing labyrinth walking from placebo effects or general relaxation.

Self-reported outcomes across multiple studies demonstrate consistent patterns: 57% of participants reported feeling “much more or more peaceful,” whilst equal percentages experienced reduced agitation. Notably, 56% reported decreased stress levels, 50% felt increased relaxation, and 44% experienced reduced anxiety. These psychological benefits correlate with measurable cardiac and respiratory changes, including reduced blood pressure and slower heart rates—physiological markers associated with parasympathetic nervous system activation.

Dr. Herbert Benson’s research at Harvard Medical School’s Mind/Body Medical Institute, spanning over 30 years, positions walking meditation within the “relaxation response” framework—a physiologically measurable state characterised by slower breathing, decreased heart rate, and lower blood pressure. This scientific validation transforms labyrinth walking from spiritual tradition to evidence-based complementary practice suitable for clinical integration.

Comparative Evidence: Labyrinth Walking vs. Alternative Interventions

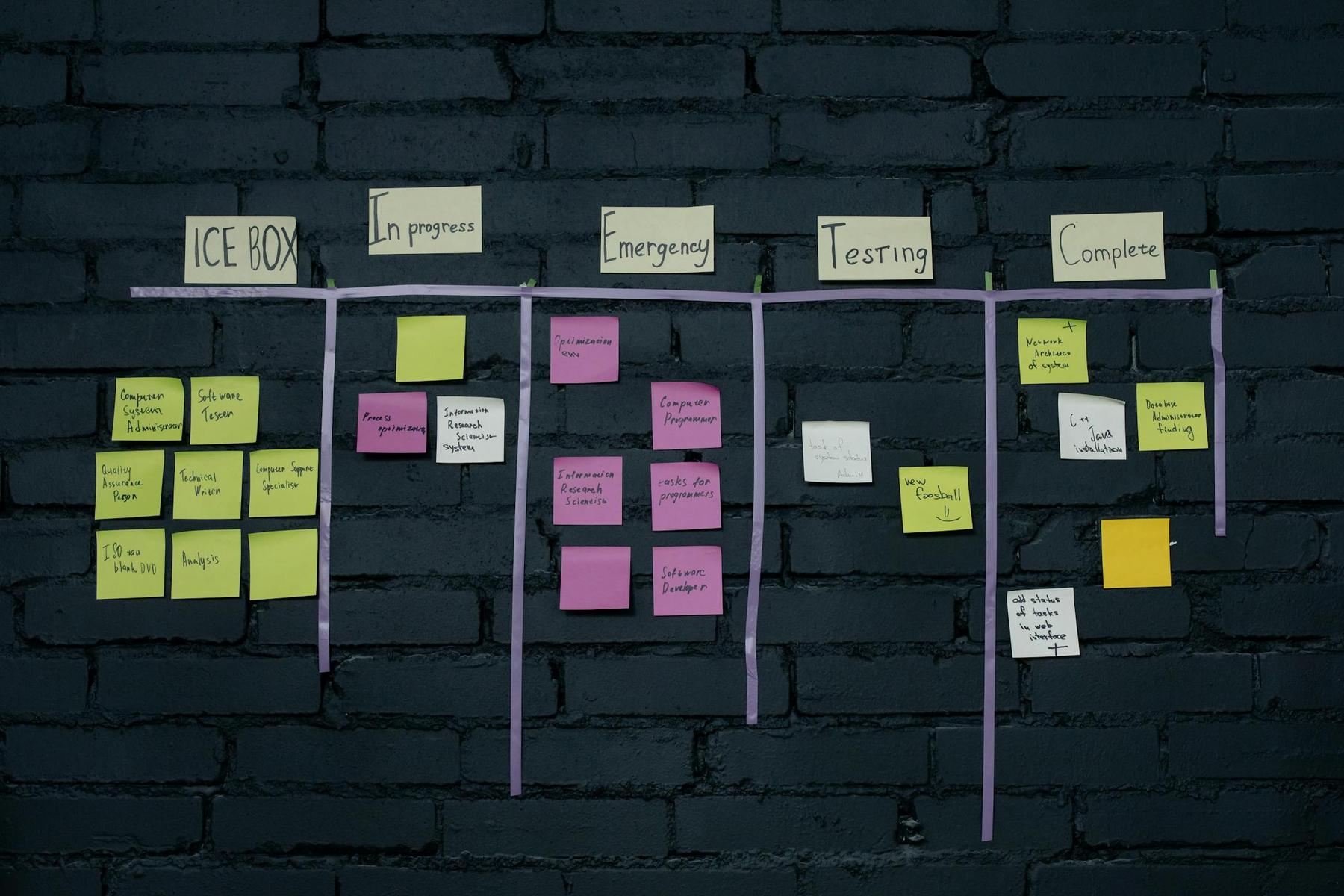

| Intervention Type | Perceived Stress Reduction | Cortisol Level Change | Effect Size (Cohen’s d) | Accessibility Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Labyrinth Walking | Large (56% reporting reduction) | 69% waking; 59% bedtime reduction | 0.65 (large) | No prior training; all fitness levels |

| Neighbourhood Walking | Small to moderate | Minimal documented change | 0.32 (small to moderate) | Basic mobility required |

| Seated Meditation | Moderate | Variable (study-dependent) | 0.40-0.55 (moderate) | Training beneficial; stillness required |

| Control (No Intervention) | Minimal | No significant change | – | – |

This comparative analysis, synthesised from multiple studies including the 2017 eight-week workplace intervention, demonstrates labyrinth walking’s superior effectiveness for perceived stress reduction compared to conventional walking or no intervention, whilst maintaining equivalent accessibility to neighbourhood walking without requiring meditation expertise.

How Does Labyrinth Walking Affect Neurological Function and Cognitive Processes?

Beyond stress markers, labyrinth walking produces measurable neurological effects documented through clinical research. Studies examining regular meditation practitioners reveal increased cortical gyrification (brain folding)—structural changes enhancing cognitive capacity in brain regions governing awareness, attention, memory, and emotion regulation. The practice activates the anterior cingulate cortex and prefrontal cortex, areas critically involved in executive function and impulse control.

A 2018 qualitative study involving 30 participants documented remarkable sensory perception alterations during labyrinth walking. An overwhelming 86.21% reported changed physical sensations, including heavy legs or sensations of “walking on water.” Additionally, 34.48% experienced altered auditory perceptions (sounds resembling falling water), 17.24% reported visual perception changes, and 13.79% experienced olfactory alterations (particularly floral scents). These perceptual shifts suggest profound alterations in sensory processing during the contemplative state.

Participants frequently described temporal and spatial perception changes—reporting feelings of being “lost in time and space” whilst maintaining full consciousness. This phenomenon relates to altered proprioception and body-ground relationship perception, indicating the practice engages neurological systems beyond simple walking mechanics. The activation of bodily and spatial memories during labyrinth walking demonstrates the brain’s integration of physical movement with cognitive and emotional processing.

These neurological effects distinguish labyrinth walking as uniquely engaging both brain hemispheres. The practice combines right-brain functions (intuition, creativity, imagery) with left-brain sequential and analytical processes required for navigating the patterned turns. This bilateral integration promotes hemispheric balance and reduces conflicts between opposing brain functions—creating what researchers describe as hemispheres working together “in peace and harmony.”

Where Can Australians Access Labyrinth Walking Opportunities in 2026?

The Australian Labyrinth Network maintains active partnerships supporting labyrinth practice throughout the continent, with Veriditas Facilitator Training providing qualified practitioners across multiple states. Perth and surrounding regions offer particularly robust accessibility, with nine documented permanent labyrinths serving diverse communities.

Notable Perth-area locations include St. Aidan’s Uniting Church (Claremont), Dayspring Centre for Christian Spirituality (Dianella), and Nathanael’s Rest (Mundaring). The Rick Hammersley Centre Reconciliation Labyrinth in Cullacabardee incorporates acknowledgement of First Nations peoples, reflecting contemporary integration of labyrinth practice with Indigenous wisdom and land recognition. Healthcare settings include the Serenity Withdrawal Unit Labyrinth (Rockingham), demonstrating clinical applications within Australian medical contexts.

The Australian Labyrinth Network coordinates World Labyrinth Day participation each May, connecting local practitioners with global synchronised walking events. During the 2021 pandemic-era celebration, over 600 participants worldwide engaged in collective labyrinth walking—with 69.3% walking outdoors and 43.8% walking alone, demonstrating the practice’s adaptability to public health requirements whilst maintaining therapeutic benefits.

Certified Veriditas facilitators operate across Queensland, New South Wales, and South Australia, offering workshops and group walks for individuals new to the practice. This expanding practitioner network ensures Australians can access qualified guidance regardless of geographic location, whilst the Worldwide Labyrinth Locator database enables individuals to identify nearby accessible sites amongst the 6,400+ registered global locations.

Accessibility considerations remain central to contemporary labyrinth design. Modern installations accommodate wheelchair users and individuals with mobility limitations, whilst finger labyrinths (paper, wooden, or metal versions for tracing) provide alternatives for those unable to walk. This inclusive approach ensures labyrinth walking’s benefits extend across demographic and ability spectrums.

What Practical Applications Extend Beyond Personal Meditation Practice?

Contemporary labyrinth implementation spans diverse institutional contexts, demonstrating the practice’s versatility beyond individual spiritual pursuits. Over 100 hospitals, hospices, and healthcare facilities throughout the United States have installed walkable labyrinths, with Australian healthcare settings increasingly following this model. Nursing staff at facilities such as Mercy Hospital (Grayling, Michigan) observe visible relaxation, decreased pulse rates, and reduced pain reports amongst patients engaging with labyrinth walking.

Educational institutions represent another significant application domain. Ten elementary schools in Santa Fe, New Mexico constructed labyrinths with documented outcomes including calmer students and increased capacity for focus—outcomes particularly relevant given contemporary concerns regarding childhood attention and emotional regulation. Universities increasingly incorporate labyrinths within campus wellness programmes, acknowledging student mental health challenges require accessible, evidence-based interventions.

Psychiatric and correctional facilities utilise labyrinth walking as therapeutic intervention. Research conducted at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst examined effects on recidivism amongst incarcerated populations, whilst the Southwest Centre for Forensic Mental Health Care documents clinical outcomes in forensic psychiatric settings. These implementations recognise labyrinth walking’s potential for insight development, tension release, and meaning-making within challenging circumstances—supporting hope, resilience, and coping mechanisms amongst vulnerable populations.

Corporate wellness programmes represent emerging application areas. The American Psychological Association headquarters in Washington, DC installed a labyrinth specifically for employee self-care, whilst medical offices integrate the practice within workplace stress reduction programmes. The 2017 workplace study demonstrating 69% cortisol reduction provides compelling rationale for employers seeking evidence-based wellness investments with measurable physiological outcomes.

Integrating Ancient Wisdom with Contemporary Holistic Wellbeing

The convergence of 4,000-year-old spiritual practice with 21st-century clinical evidence exemplifies humanity’s capacity to preserve wisdom traditions whilst subjecting them to rigorous scientific scrutiny. Labyrinth walking’s documented benefits—from cortisol reduction to enhanced cognitive function—validate ancestral knowledge through methodologies our predecessors could never have imagined. This synthesis of ancient and modern perspectives creates pathways for individuals seeking comprehensive wellbeing approaches addressing physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual dimensions simultaneously.

The practice’s accessibility remains perhaps its most remarkable characteristic. Unlike interventions requiring specialised equipment, extensive training, or particular physical capabilities, labyrinth walking welcomes participants regardless of age, fitness level, meditation experience, or spiritual orientation. The unicursal path eliminates performance anxiety inherent in maze-solving or complex practices—there exists genuinely “no wrong way” to walk a labyrinth. This non-judgmental framework supports individuals hesitant about meditation practices perceived as requiring expertise or particular mindsets.

Australia’s growing labyrinth network, coupled with global expansion reaching 6,400+ registered sites, ensures geographical accessibility whilst maintaining practice integrity through certified facilitator training. The integration of First Nations acknowledgement within Australian labyrinths demonstrates cultural sensitivity and recognition of Indigenous contemplative traditions predating European labyrinth introduction. This respectful syncretism honours multiple wisdom lineages whilst creating inclusive spaces for diverse communities.

As Australian healthcare systems increasingly recognise integrative approaches complementing conventional interventions, evidence-based practices like labyrinth walking occupy expanding roles within comprehensive care frameworks. The practice’s documented stress-reduction capabilities, cognitive benefits, and emotional regulation support align with contemporary understanding of mind-body connections whilst respecting individual autonomy regarding spiritual interpretation. Whether approached as sacred pilgrimage, psychological intervention, physical exercise, or simple quiet contemplation, labyrinth walking accommodates multiple intentions whilst delivering consistent measurable benefits.

Looking to discuss your health options? Speak to us and see if you’re eligible today.

How does labyrinth walking differ from regular walking for stress reduction?

Clinical research demonstrates labyrinth walking produces significantly larger stress reduction effects compared to neighbourhood walking. An eight-week study comparing both interventions found labyrinth walking achieved large effect sizes (Cohen’s d = 0.65) for perceived stress reduction, whilst neighbourhood walking showed only small to moderate effects (0.32). The intentional, meditative quality of labyrinth walking—following a predetermined path without navigational decisions—activates different neurological processes than recreational walking. Additionally, labyrinth walking produced 69% cortisol reduction in waking levels and 59% reduction in bedtime levels, substantially exceeding conventional walking outcomes. The practice combines physical movement with contemplative focus, creating a unique ‘active meditation’ that many individuals find more accessible than seated practices.

Can people with mobility limitations participate in labyrinth walking?

Yes, labyrinth walking is designed to be inclusive. Wheelchair-accessible outdoor labyrinths and barrier-free indoor designs ensure that those with mobility limitations can participate. For individuals with significant restrictions, finger labyrinths, which involve tracing a labyrinth pattern on paper, wood, or metal, offer a viable alternative that still promotes a meditative state and stress-reduction benefits. Additionally, emerging virtual reality applications further expand accessibility for those unable to access physical sites.

What is the recommended duration and frequency for labyrinth walking practice?

Research protocols typically involve an eight-week period with regular sessions. Individual sessions usually last the time needed to complete the labyrinth path—often between 20 to 40 minutes—depending on the labyrinth’s size and the walking pace. While some practitioners may choose to pause at the centre for extended meditation, regular practice (weekly or multiple times per week) tends to produce more substantial cumulative benefits.

Is labyrinth walking associated with specific religious traditions, or can it be practised secularly?

Labyrinth walking has historical ties to various religious and spiritual traditions, particularly within Christian contexts, but it is equally effective and accessible as a secular practice. Its mechanism—combining physical movement with contemplative focus along a predetermined path—operates independently of any specific religious belief. This universality makes it suitable for individuals of diverse spiritual orientations or those seeking a purely evidence-based approach to stress reduction and cognitive enhancement.

What evidence exists for labyrinth walking’s effectiveness compared to other meditation practices?

Multiple clinical studies have compared labyrinth walking to other interventions, such as fast-paced walking and seated meditation. Findings indicate that labyrinth walking can produce comparable improvements in stress reduction and cognitive function without the need for extensive training. For instance, studies have shown reductions in cortisol levels and significant improvements in perceived stress scores that rival those seen in traditional meditation programmes. Additionally, neurological research has documented brain structural changes similar to those observed in regular meditation practitioners, underscoring its effectiveness as a mind-body intervention.